Chartwell: Churchill’s Country Seat in Westerham, Kent

By Barbara Israel

Last June I had the pleasure of visiting Chartwell on a perfect-for-pictures overcast day. Knowing that Sir Winston Churchill (1874-1965) had been raised at Blenheim Palace I wasn’t sure what to expect. Would grand gestures dominate the house and gardens? It didn’t take long for me to realize that that was not the case. In fact, I was greeted by a beautifully understated, rolling landscape surrounding a very large but plain unembellished brick house.

All photos of grounds: Barbara Israel

As I walked along the visitor’s entrance I came across gardens that were inviting and intimate appearing to express the tastes and interests of the homeowners rather than those of a landscape professional. A particular garden caught my eye and I was to find out later that it had been one of Mr. Churchill’s treasured spots where he’d sat for many hours watching and feeding his fish from his favorite chair. The fish that he preferred above all others was the “golden orfe” (Leuciscus idus), an ornamental freshwater specimen that was commonly used until later when “koi” became popular in pond collections. Apparently when Churchill was away from Chartwell he was often known to worry about the welfare of his fish.

As I walked along the visitor’s entrance I came across gardens that were inviting and intimate appearing to express the tastes and interests of the homeowners rather than those of a landscape professional. A particular garden caught my eye and I was to find out later that it had been one of Mr. Churchill’s treasured spots where he’d sat for many hours watching and feeding his fish from his favorite chair. The fish that he preferred above all others was the “golden orfe” (Leuciscus idus), an ornamental freshwater specimen that was commonly used until later when “koi” became popular in pond collections. Apparently when Churchill was away from Chartwell he was often known to worry about the welfare of his fish.

Adjacent to that garden was a small system of waterfalls that looked as if they’d always been there. It is well known that Churchill loved water gardens and had this one created to his liking. When he bought Chartwell and 92 of its acres Churchill kept two of the original workers, one of whom, the aptly named Edmund Waterhouse, was a gardener who was “good with the water system”. (Churchill and Chartwell: The Untold Story of Churchill’s Houses and Gardens by Stefan Buczacki, London: Frances Lincoln, 2007, p. 156) Possibly what Churchill had grasped from Blenheim was the impression of the vast landscape that had been shaped by the renowned landscape architect Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1715-1783) into “a landscape of trees, contrived vistas and water.” (Buczacki, p. 3)

Adjacent to that garden was a small system of waterfalls that looked as if they’d always been there. It is well known that Churchill loved water gardens and had this one created to his liking. When he bought Chartwell and 92 of its acres Churchill kept two of the original workers, one of whom, the aptly named Edmund Waterhouse, was a gardener who was “good with the water system”. (Churchill and Chartwell: The Untold Story of Churchill’s Houses and Gardens by Stefan Buczacki, London: Frances Lincoln, 2007, p. 156) Possibly what Churchill had grasped from Blenheim was the impression of the vast landscape that had been shaped by the renowned landscape architect Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1715-1783) into “a landscape of trees, contrived vistas and water.” (Buczacki, p. 3)

Sir Winston and his wife Lady Clementine (1885-1977) had bought Chartwell in 1922 but it took a number of years and many financial setbacks before the house and grounds were completed to their satisfaction. As the big lake came into sight on my left I remembered reading that one of Churchill’s changes was that he had turned a small pond into a series of significant lakes. As I looked around it appeared to be populated with Canadian geese, but none of the famed black swans were in sight. Sir Winston’s close friend Philip Sassoon had given him the first black swans (C. atratus) in 1927 and a black swan population has been maintained there ever since. Recently the keepers had to construct a floating island in the lake in order to keep the swans’ four-legged predators at bay. During Churchill’s lifetime there were rumors that he loved these birds to such an extent that he had been known to speak “swan talk” to them!

The sweeping feel of the property and its massive open spaces and views are what first attracted Churchill to Chartwell. (Buczacki, p. 156) And why, when he had lived in so many houses throughout Great Britain, did his heart select Kent? Surprisingly, his nanny, Elizabeth Everest, who had been a significant friend and mentor to him for years, had loved Kent and thought it “the centre of the world.” (Buczacki, p. 5)

At last we get to Clementine, who is credited with the rose garden but was known for her great taste in colors and was very exacting about trees. (Buczacki, p. 157) Her original plantings have not survived but a soft blousy feeling has been maintained in various places, namely along the steps to the entrance court.

At last we get to Clementine, who is credited with the rose garden but was known for her great taste in colors and was very exacting about trees. (Buczacki, p. 157) Her original plantings have not survived but a soft blousy feeling has been maintained in various places, namely along the steps to the entrance court.

The old specimen trees are spectacular and provide a dramatic contrast with the extensive green expanses.

As I walked toward the house I began to realize how large it was and decided that the blank brick walls must have once had vines covering them. Churchill had hired Philip Tilden, a young architect, to redo the house in 1922. As one author said, that selection was “a decision made in haste and repented at leisure.” (No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money by David Lough, New York: Picador, 2015, p. 149) Tilden initially described the house as “A dreary house perched on the edge of a hillside….the rest of it was weary of its own ugliness so that the walls ran with moisture, and creeping fungus tracked down the cracks and crevices.” Not a sanguine start that forecast their contentious relationship. One might have thought that Sir Winston and Lady Clementine would have had sufficient funds to buy and redo a house but that was not the case at all. They were constantly in financial trouble whether it was from one of his gambling debts or an unwise investment. At one point Churchill lost $50,000 in the crash of 1929 after he had bought securities on the NY Stock Exchange. He had to return to England and admit his losses to Clementine, yet again limiting their budget for the house. (Buczacki, p. 157) It is fascinating that someone who was Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1924 to 1929 had trouble handling his personal finances!

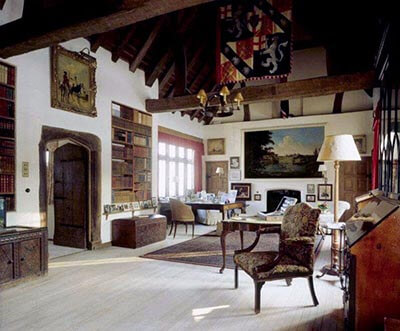

Photos were not permitted in the interior of the house but I think we can make up for that with a few from the National Trust’s Chartwell listing. My impression was one of a comfortable, low-key English country house with soft colors, big sofas and chintz curtains that created a livable, welcoming atmosphere. Nevertheless, the painting collection is anything but ordinary.

In addition to numerous paintings by Churchill himself the living room boasted a showstopper Claude Monet Pont de Londres seen on the right wall above. The self-tour began upstairs and gradually proceeded down through small corridors, through bedrooms, meeting rooms, and into Churchill’s rather palatial study with its high vaulted ceiling, exposed beams and Tudor style furnishings.

In addition to numerous paintings by Churchill himself the living room boasted a showstopper Claude Monet Pont de Londres seen on the right wall above. The self-tour began upstairs and gradually proceeded down through small corridors, through bedrooms, meeting rooms, and into Churchill’s rather palatial study with its high vaulted ceiling, exposed beams and Tudor style furnishings.

The top floor of the house has a museum that exhibits old uniforms and memorabilia. If the opportunity arises to visit Chartwell be sure to leave extra time to sort through the extraordinary collections in the house and grounds. I totally regret that I never made it to Sir Winston’s studio in one of the outbuildings, but another time.

Because of the Churchill family’s continuing financial issues The National Trust took over Chartwell in 1946-47 but Sir Winston and Lady Clementine were accorded a lifetime residency and lived there until his death in 1965. Even with the extraordinary demands on his life and constant travels abroad Churchill returned time and again to the tranquility of Chartwell, the ballast in a turbulent life.

Exhibition of American Sculpture, April-August 1923 – Part One

By Eva Schwartz

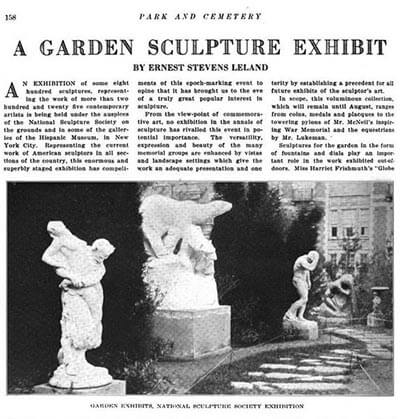

Isn’t it the case, when researching, that some of the best discoveries happen entirely by chance? Years ago when we were working on the “Landscaped Cemeteries” issue of Focal Points, I came across an article, in among editorials on proper grave preparation and the current fashion in headstones, in the August 1923 edition of Park and Cemetery, a trade journal for the cemetery industries. The article, titled “A Garden Sculpture Exhibit”, reviews a groundbreaking exhibition of American sculpture of which none of us had ever heard, despite having been the most ambitious show of its kind, and the second largest ever (still to this day). The exhibition was held in New York City from April to August, 1923 and was jointly sponsored by the National Sculpture Society and the Hispanic Society. All these years later, it seems to have received very little attention from historians, and I could find no recent scholarship highlighting or even weighing its importance. I marveled at what an incredible undertaking this must have been–to have sourced and assembled nearly 800 sculptures by American artists, ranging from the tiniest medals to monumental works of marble and bronze. I wanted to know more; who dreamed this show up and who made it happen?

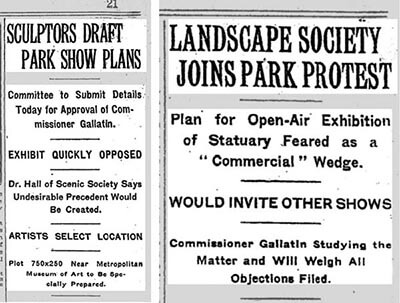

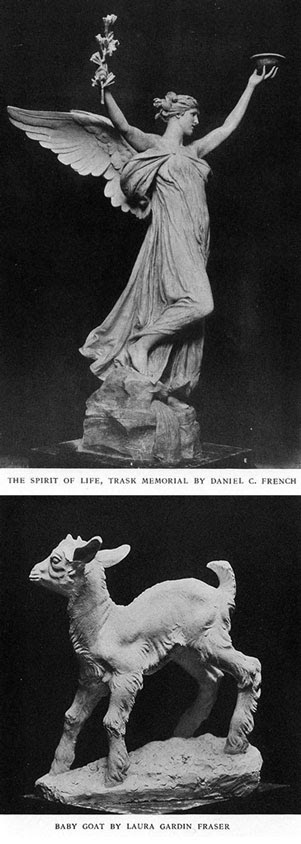

Of course the best place to start when seeking the why and how of things like this is to dive into writings from the period. I found several articles in The New York Times from April 1922, a year prior to the opening of the show, chronicling a fiery debate over whether a large sculpture show should be held in Central Park. To read these articles, you’d think the most weighty issues of morality were at stake! The proposed Central Park exhibition would have been a modest assemblage of 50 to 100 works and was to have been held on a grassy site just north of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (above). The plan had the support, unsurprisingly, of prominent sculptors including Daniel Chester French (1850-1931), who was Honorary President of the National Sculpture Society at the time. As reported by The New York Times on April 5, 1922, Mr. French met with Park Commissioner Francis D. Gallatin to discuss the merits of the proposal, including the benefits of exhibiting garden and park sculptures in an outdoor setting, where they’d be shown to the best effect. The idea was to elevate and promote an American school of sculpture that was still struggling to distinguish itself as something separate from and equal to its European counterparts. (Photo: By Jfcapdet – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34873260)

Of course the best place to start when seeking the why and how of things like this is to dive into writings from the period. I found several articles in The New York Times from April 1922, a year prior to the opening of the show, chronicling a fiery debate over whether a large sculpture show should be held in Central Park. To read these articles, you’d think the most weighty issues of morality were at stake! The proposed Central Park exhibition would have been a modest assemblage of 50 to 100 works and was to have been held on a grassy site just north of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (above). The plan had the support, unsurprisingly, of prominent sculptors including Daniel Chester French (1850-1931), who was Honorary President of the National Sculpture Society at the time. As reported by The New York Times on April 5, 1922, Mr. French met with Park Commissioner Francis D. Gallatin to discuss the merits of the proposal, including the benefits of exhibiting garden and park sculptures in an outdoor setting, where they’d be shown to the best effect. The idea was to elevate and promote an American school of sculpture that was still struggling to distinguish itself as something separate from and equal to its European counterparts. (Photo: By Jfcapdet – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34873260)

From a high-minded artistic standpoint, perhaps the exhibition should have been an easy sell. However, the Central Park proposal was met with such hostile and suspicious outrage that it never came to fruition. Despite the initial “cordial approval” of the Park Commissioner, the proposal was opposed by key stakeholders, including the Parks and Playgrounds Association, which found it to be “an encroachment on park space”. The Secretary of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society was strongly against, advising that “the purpose of the exhibition was to advertise sculpture” and that it would be a “great mistake” to allow the park to be used for any commercial purpose (he clearly saw it as a slippery slope). Senator Nathan Straus Jr. warned that “if permission [were] granted for this…exhibition, it [would] make the task of those interested in conserving the parks more difficult the next time an improper invasion is suggested”.

From a high-minded artistic standpoint, perhaps the exhibition should have been an easy sell. However, the Central Park proposal was met with such hostile and suspicious outrage that it never came to fruition. Despite the initial “cordial approval” of the Park Commissioner, the proposal was opposed by key stakeholders, including the Parks and Playgrounds Association, which found it to be “an encroachment on park space”. The Secretary of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society was strongly against, advising that “the purpose of the exhibition was to advertise sculpture” and that it would be a “great mistake” to allow the park to be used for any commercial purpose (he clearly saw it as a slippery slope). Senator Nathan Straus Jr. warned that “if permission [were] granted for this…exhibition, it [would] make the task of those interested in conserving the parks more difficult the next time an improper invasion is suggested”.

I understand their point; certainly the merit of such a show should have been weighed against any commercial repercussions. After all, any pandering to commercialism would go against a fundamental ideal of the city parks movement: that parks are for everyone, and are thereby not for the profit-seeking of a few. However, I can also imagine how frustrating it must have been for artists seeking public support and appreciation for the work they were doing, especially since art in the public sphere can be a real force for good. Consider Gutzon Borglum’s argument in favor of the Central Park show, put forth in his New York Times op-ed dated April 6, 1922, in which he condemns the Parks Department’s decision. Borglum, the sculptor famous for the Mount Rushmore monument held, it must be said, very despicable personal views on race and immigration, but reasoned, ironically, that for city officials “to treat everything as an invasion is to admit a habitual state of prejudice rather than judgment. If the Sculpture Society should propose to string sculpture up and down the center of a congested street, there is debatable ground for admitting this as unwise or not good taste,” but, Borglum argued, a sculpture show in Central Park was a perfectly advisable, and wise, idea.

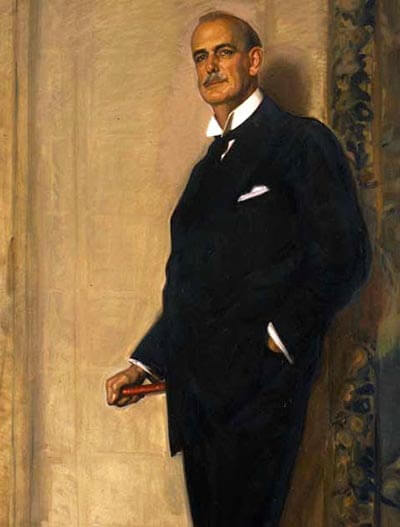

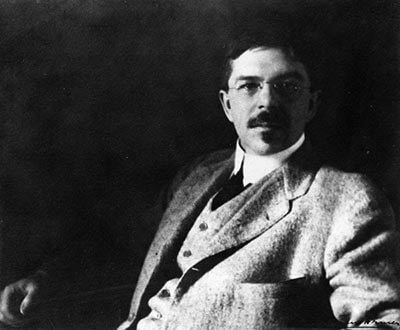

Archer Milton Huntington, ca. 1930, by José María López Mezquita.

Image courtesy The Hispanic Society.

Still, the Central Park plan was not to be. Minutes from the National Sculpture Society meeting held on May 9, 1922 indicate that by then the Society had abandoned the proposal, as any further attempts to push the issue may well have required a court battle–and they simply didn’t have the financial capacity to go that far. An idea was floated to hold the show at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, but it fizzled due to lack of enthusiasm and follow-up–and this came after exhausting other Manhattan park locations, including Gramercy Park and Union Square. Then, in October, 1922, the sculptor and exhibition committee member, Chester Beach (1881-1956), suggested asking Archer Huntington if he might be open to collaboration.

Archer Milton Huntington (1870-1955), a philanthropist with a true passion for art, turned out to be exactly the sort of benefactor the Society needed to get the project off the ground. After meeting with committee members, Archer Huntington offered not only to host the exhibition, but to finance it as well. (He drew the line at paying transportation costs for sculptures coming from far and wide–but once they were on site, he’d cover everything. He simply asked that the committee make every effort to mount “the finest exhibition of sculpture ever set up”.)

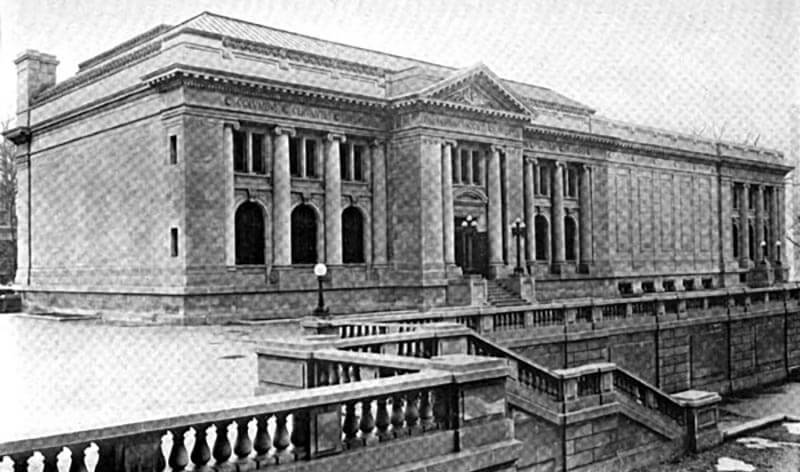

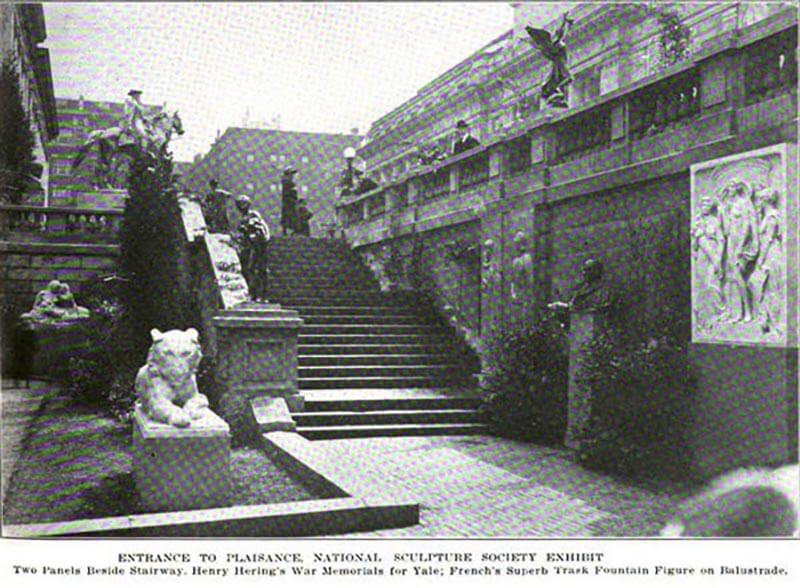

The exhibition would be held at the Audubon Terrace, the museum campus anchored by the Hispanic Society (right) and the American Geographical Society, on 155th Street and Broadway in Manhattan. In many ways it was a logical choice for the show, considering the backdrop of splendid Beaux-Arts architecture and the devotion to artistic pursuit maintained by Huntington, who, as the site’s founder and patron, had commissioned the first of the Terrace buildings in 1907 (construction lasted until 1930). However, the logistical challenge the location presented was no trifling thing. The multi-leveled arrangement of the terraces (depicted below), limited access from the street, mixture of indoor and outdoor display areas, and the out-of-the-way neighborhood must have made things difficult, especially for the riggers who did the heavy lifting! (Photo: By Sailko – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31583204)

The exhibition would be held at the Audubon Terrace, the museum campus anchored by the Hispanic Society (right) and the American Geographical Society, on 155th Street and Broadway in Manhattan. In many ways it was a logical choice for the show, considering the backdrop of splendid Beaux-Arts architecture and the devotion to artistic pursuit maintained by Huntington, who, as the site’s founder and patron, had commissioned the first of the Terrace buildings in 1907 (construction lasted until 1930). However, the logistical challenge the location presented was no trifling thing. The multi-leveled arrangement of the terraces (depicted below), limited access from the street, mixture of indoor and outdoor display areas, and the out-of-the-way neighborhood must have made things difficult, especially for the riggers who did the heavy lifting! (Photo: By Sailko – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31583204)

Photo: By Unknown photographer – Encyclopedia Americana, v. 17, 1920, between pp. 366 and 367 first photograph, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18737201

Naturally, I contacted the Hispanic Society for archival material on the show and received the shattering news that most of the records relating to the show were discarded by none other than Mr. Huntington. What’s more, I wouldn’t be able visit the building or terraces until at least 2019 due to a major renovation that was underway. Luckily, I had extensive meeting minutes (spanning 1921-1923) provided by the National Sculpture Society (NSS). (I just about flipped when their generous archivist, Elizabeth Helm, sent them over.)

From 1921 to 1923, the Exhibition Committee members varied a bit, but the core group working on behalf of the show were: Robert Aitken, Adolph Alexander (A.A.) Weinman, Herman MacNeil (who all served as Chairman at different points), Herbert Adams, Daniel Chester French, Chester Beach, Anna Hyatt, Adeline Adams, Harriet Frishmuth, Frederick Roth, Leo Lentelli, and, of course, Archer Huntington. As these were some of the biggest personalities in the art world, there were lots of different opinions about how the show should be mounted, but uniform sentiment concerning its overarching purpose.

At the May 9, 1922 meeting, outgoing NSS President, Robert Aitken, lamented their failure to implement the outdoor exhibition of their dreams, stating that should they ever make a success of it, they’d do it in spite of the utter lack of support from city agencies, and they’d do it as a “slap in the face” to New York–a slap that would teach the city how critical it was to support its artists. He also expressed the necessity of educating children so that they could become an “intelligent audience for the future”. Incoming President, Herman MacNeil, stressed the importance of keeping sculpture, and art in general, in the public eye. He viewed it as “an irresistible force meeting an immoveable object”, whereby Art was the force and the City was the object. With every successful action, they would make a dent in that immoveable object–and over time the dents would widen.

Aitken and MacNeil, and fellow members of the NSS, were reacting to a long-held belief–some would call it a myth–that American sculptors were inferior to European sculptors not only in training and experience, but also with regard to the more elusive quality of depth, or soul. In the early years of our nation’s history, there simply wasn’t a sculpture school of note, which meant that any significant commissions were given to European artists. The marble statue of George Washington commissioned in 1784 by the Virginia General Assembly, for example, was executed by the great Frenchman, Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828). Later, even after there were competitive art institutions in the States, American sculptors were compelled to study in Europe to complete, or legitimize, their education. (Photo: By Mrssisaithong – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21657314)

Aitken and MacNeil, and fellow members of the NSS, were reacting to a long-held belief–some would call it a myth–that American sculptors were inferior to European sculptors not only in training and experience, but also with regard to the more elusive quality of depth, or soul. In the early years of our nation’s history, there simply wasn’t a sculpture school of note, which meant that any significant commissions were given to European artists. The marble statue of George Washington commissioned in 1784 by the Virginia General Assembly, for example, was executed by the great Frenchman, Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828). Later, even after there were competitive art institutions in the States, American sculptors were compelled to study in Europe to complete, or legitimize, their education. (Photo: By Mrssisaithong – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21657314)

In his review of the 1923 Exhibition of American Sculpture, Royal Cortissoz (1869-1948), the outspoken art critic for the New York Herald Tribune from 1891 to 1948, mostly praised the show, but also regretted what he took to be American artists’ failure to harness the “power of invention…[or] the magic of style” (see “The American School of Sculpture”, in the New York Tribune, April 22, 1923). As a strict traditionalist, even long after modernism had taken hold, he advocated for an adherence to Classical European standards of modeling and form, but at the same time decried American artists’ dearth of originality or visionary spirit. This seems rather unfair–but it speaks to the widespread snobbishness toward American sculptors and represents the very attitudes that the National Sculpture Society sought to overturn.

In his review of the 1923 Exhibition of American Sculpture, Royal Cortissoz (1869-1948), the outspoken art critic for the New York Herald Tribune from 1891 to 1948, mostly praised the show, but also regretted what he took to be American artists’ failure to harness the “power of invention…[or] the magic of style” (see “The American School of Sculpture”, in the New York Tribune, April 22, 1923). As a strict traditionalist, even long after modernism had taken hold, he advocated for an adherence to Classical European standards of modeling and form, but at the same time decried American artists’ dearth of originality or visionary spirit. This seems rather unfair–but it speaks to the widespread snobbishness toward American sculptors and represents the very attitudes that the National Sculpture Society sought to overturn.

(Photo: By Unidentified photographer, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5235844)

Photo: By Unknown photographer – Encyclopedia Americana, v. 17, 1920, between pp. 366 and 367 first photograph, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18737201

In the late 19th century, as the Industrial Revolution brought mass production–and the fear of overproduction–a palpable longing burst forth in defense of handwork. We see this in the lasting influence of the Arts & Crafts movement, for instance. But the anti-industrial tide also led to a certain backlash against Sculpture, in favor of Painting. Paintings, particularly those produced by the Impressionist and other modern movements, tended to be singular works representing one artist’s individual expression, whereas sculptures were inherently associated with multiple casts and a more assembly-line style of production (as documented in the above image of a sculpture studio in Weehawken, NJ, 1904). After all, sculptors relied on the assistance of many studio hands (from the mold maker to the apprentice carver) to complete a work in bronze or marble–and to some, this made Sculpture the less-personal, and more-commercial, art form. [Please see Victorian scholar, Angela Dunstan’s “Nineteenth-Century Sculpture and the Imprint of Inauthenticity” in Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century (2014) for an excellent discussion on the efforts by Victorian-era artists and writers to win over naysayers.]

We must, then, bear all of this history in mind when examining the 1923 exhibition. The committee was charged not only with elevating American sculpture, beyond the European canon, but also with stirring fresh appreciation for the dignity of the medium itself.

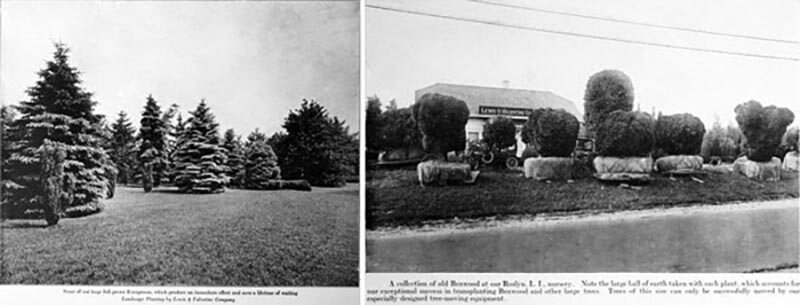

Photos: Canadian Centre for Architecture – Lewis & Valentine, c. 1922

After having at last secured the venue, the committee got down to brass tacks. They immediately approached the Lewis & Valentine Company, the preeminent nursery best known for masterfully moving mature trees (above). When the Central Park plan had been in play a year prior, the firm had agreed to furnish all trees, shrubs, and decorative plants at no cost to the committee, so naturally the committee hoped they could count on the same level of generosity. Additionally, the committee contacted James Greenleaf (1857-1933), a leading landscape architect, for advice on landscape design. Greenleaf had designed landscapes for some of the finest properties on the east coast, including Blairsden (completed 1903), in Peapack, New Jersey, where he learned firsthand the challenges of hauling mature trees. [See Barbara Israel, Antique Garden Ornament: Two Centuries of American Taste (Abrams, 1999) for more on Blairsden.]

Ultimately, though, Greenleaf must have turned down the job, as the landscape design was handed over to Ferruccio Vitale (1875-1933), one of the brightest minds in landscape architecture in the early 20th century, and the President of the New York Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects at the time of the exhibition. Happily, he agreed to take up the work of the show (and for free)–which would require the transformation of architectural terraces into garden-like display areas. He warned, though, that Lewis & Valentine, with whom he had a very close working relationship, would be astonished by the vastness of the terraces and the plethora of plant specimens required. Vitale was correct–Lewis & Valentine did get cold feet when they saw what would be required (remember, it would be nearly 800 sculptures in the end, eight times larger than what had been proposed for Central Park). Vitale passed on a message at the December 22, 1922 meeting that if “there [were] any way [for Lewis & Valentine] to drop out they would be glad to do so”. Fortunately, the nurserymen hung in there, though there would be some negotiation with regard to price. (Photo: By Unknown – Ferruccio Vitale: Landscape Architect of the Country Place Era, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61340284)

Ultimately, though, Greenleaf must have turned down the job, as the landscape design was handed over to Ferruccio Vitale (1875-1933), one of the brightest minds in landscape architecture in the early 20th century, and the President of the New York Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects at the time of the exhibition. Happily, he agreed to take up the work of the show (and for free)–which would require the transformation of architectural terraces into garden-like display areas. He warned, though, that Lewis & Valentine, with whom he had a very close working relationship, would be astonished by the vastness of the terraces and the plethora of plant specimens required. Vitale was correct–Lewis & Valentine did get cold feet when they saw what would be required (remember, it would be nearly 800 sculptures in the end, eight times larger than what had been proposed for Central Park). Vitale passed on a message at the December 22, 1922 meeting that if “there [were] any way [for Lewis & Valentine] to drop out they would be glad to do so”. Fortunately, the nurserymen hung in there, though there would be some negotiation with regard to price. (Photo: By Unknown – Ferruccio Vitale: Landscape Architect of the Country Place Era, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61340284)

At an earlier meeting on December 12th, Ferruccio Vitale expressed his great enthusiasm for the sculpture show, commenting that it was about time, as other nations had done similar things to much fanfare. It shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s read anything about Vitale–possibly the most influential, yet least known, landscape architect of the last century–that he wholeheartedly supported the endeavor. He was a crusader for education, and for the causes of fine art, architecture, and design, and was a constant advocate for public outreach. He promoted landscape architecture as something worthy of being cherished, saved, and studied. So of course, in this way, he was perfectly aligned with the National Sculpture Society; both sought to elevate the standing of their art form, extend influence, and educate the public.

Photo: By PVSBond at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8989362

The task of transforming the large all-masonry terraces at the Audubon complex into a garden, while no doubt daunting, was still a great deal simpler than Vitale’s other professional projects. By 1922, he had already completed Longwood (above), the Pierre S. duPont estate in Kennett Square, PA (1915), and at least 16 other major commissions throughout the northeast. He was known as a sort of rebel among his contemporary colleagues, as he pushed against the prevailing style of the period, which had long been guided by the gifted hand of Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) and his faithful followers. Vitale, born in Italy, was a student of the formal Italianate garden, and his designs adhered to an ordered methodology that complemented architectural principles. He habitually challenged the Picturesque, romantic approach to landscape design that Olmsted had popularized. [For a comprehensive study of Ferruccio Vitale’s work, see R. Terry Schnadelbach’s outstanding book, Ferruccio Vitale: Landscape Architect of the Country Place Era (Princeton Architectural Press, 2001).]

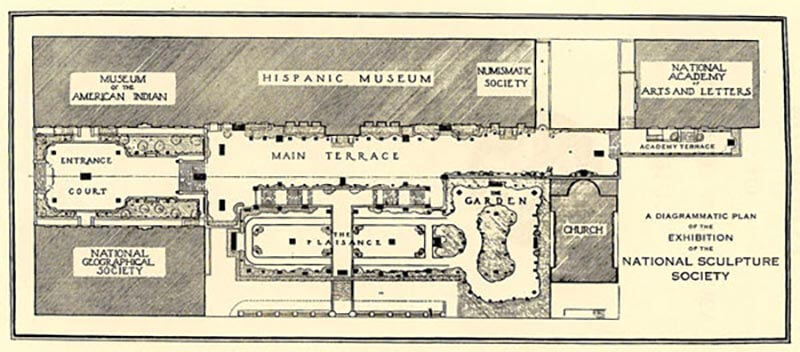

Illustration from the 1923

Exhibition of American Sculpture Guide, p.2.

At the December 12th meeting, Vitale laid out his plan for the exhibition. He loved the multi-leveled terraces of the site, feeling that the different vantage points and room-like arrangement of the spaces would enhance the visitor’s experience. He planned to create a “Court of Honor” on the lowest terrace where the most exceptional works could be featured. He also advocated for the creation of swaths of lawn and groupings of mature trees, hedges, and shrubs to sufficiently green-up the space. Most importantly, his design would take its cue from the sculptures themselves, and would be inspired not only by their subject matter, but by their scale. Granted, no one yet knew exactly which works they’d have on view for the April opening, so Vitale had to be flexible, to say the least.

At the December 12th meeting, Vitale laid out his plan for the exhibition. He loved the multi-leveled terraces of the site, feeling that the different vantage points and room-like arrangement of the spaces would enhance the visitor’s experience. He planned to create a “Court of Honor” on the lowest terrace where the most exceptional works could be featured. He also advocated for the creation of swaths of lawn and groupings of mature trees, hedges, and shrubs to sufficiently green-up the space. Most importantly, his design would take its cue from the sculptures themselves, and would be inspired not only by their subject matter, but by their scale. Granted, no one yet knew exactly which works they’d have on view for the April opening, so Vitale had to be flexible, to say the least.

And what of the sculptural works themselves? The committee had created a Subcommittee on Solicitation that had undertaken the tremendous task of sourcing, vetting, and selecting pieces to be seen by the jury. Apparently, this process was quite slow-going at first, to the point that A.A. Weinman (1870-1952), the preferred sculptor of the McKim, Mead, and White architectural firm, and a member of the committee, expressed his utter dismay at the slogging pace (never mind that they had just settled on a venue two months before). At the December 12th meeting, Weinman reported that he had sent out plenty of notices, but sculptors were not responding nearly fast enough. He had only received 50 photographs from a total of 25 members of the NSS! [Weinman comes across as quite the taskmaster in the NSS meeting minutes.]

The selection jury included Herbert Adams, Daniel Chester French, James Fraser, A.A. Weinman, Edward McCartan, Isidore Konti, Bessie Potter Vonnoh, and Anna Hyatt (who met and became engaged to marry Archer Huntington as a result of the exhibition). They judged works mainly from photographs, and were occasionally forced to choose based on the quality of the images (understandably, considering that those very images would be reproduced for the 375-page catalog). Some of the sculptures were gigantic installations that couldn’t actually be transported to the Audubon Terrace, so the committee made plans to create a photo gallery indoors at the Hispanic Society, where they would also display the smallest sculptures and medals. (Photos from the 1923 Exhibition of American Sculpture Catalogue, pp. 71 and 68.)

Photo from Ernest Stevens Leland, “A Garden Sculpture Exhibit”,

Park and Cemetery, August 1923.

By February, 1923, they were no longer having trouble eliciting responses from Society members; to the contrary, the committee was now faced with finding space for the hundreds of pieces that had already been selected, in addition to those that were still being submitted. Mr. Weinman was again perturbed by exhibitors’ inadequacies as he complained on March 20, 1923 (only 23 days before the Press Opening) that “much of the work promised had not been delivered” and he bemoaned having been “inconvenienced by the non-delivery of promised work”. Indeed, one quickly grasps from reading the meeting minutes that the installation was plagued with headaches. One logistical issue was finding a carpenter who would build standard wooden pedestals quickly and for the right price ($3.50-4.00 per piece, stained “flat brown”). Another stumbling block: the multiple staircases at the site. Huntington arranged to build temporary wooden ramps to make it possible for Mr. Walthausen, the rigger, to access the upper terraces from the street. [Mr. Walthausen received $25 a day for his services, which covered his time and the machines needed for hoisting, but did not include his laborers, who were each paid $7 a day.] With loads of large sculptures arriving from across the country, one can see how the expenses would quickly add up. By late March, expenditures totaled $3,000, which was more than half of Mr. Huntington’s proposed budget of $5,000.

In the sprint up to opening day–press opening was on April 12th and public opening on April 14th–the committee was madly focused on getting the publications compiled and sent to the printer. In addition to the illustrated exhibition catalog that included biographical sketches of 106 sculptors and a list of exhibited works, the committee produced a tidy volume on the history of American sculpture, titled The Spirit of American Sculpture. Initially, the task of writing this companion book was assigned to Daniel Chester French, as he was Honorary President of the National Sculpture Society and arguably its most famous member, but he quickly bowed out due to other obligations. Sculptor Lorado Taft (1860-1936) was the committee’s second choice, but he, too, politely declined. The job then fell to Adeline Adams (1859-1948), an art writer and critic and the wife of sculptor Herbert Adams (1858-1945). It’s a good thing it did, too, as the result is a sensitively-written and informative text, peppered with witticisms and opinionated musings. Adams wasn’t a sculptor, but was a Lay Member of the Society, and an astute historian. She published seven books over the course of her career, many of them monographs of great artists like John Quincy Adams Ward (1830-1910). With The Spirit of American Sculpture, she sets the 1923 show in context, with both a thorough examination of the past, and a hopeful look toward the future:

We sometimes worry ourselves unnecessarily because our arts and letters are not

what is called “distinctively American”. But being distinctively American is not

in itself a merit. The distinctively American voice, for example, has not yet been

hailed as the international model. Give our sculpture time for still further

expression, and it will become as distinctively American as need be.

Adams further illuminates that “the story of American sculpture cannot be told under a parable of a chain with equally strong links throughout. One thinks rather of a slender thread, which may be fastened to a cord, which will draw up a strong rope, which will in turn attach itself to a powerful cable”. It was with this tremendous sense of optimism that the Exhibition opened on April 12, 1923.

Photo from “A Notable Exhibition of American Sculpture”,

The American Architect: The Architectural Review, May 9, 1923, Vol. CXXIII, Number 2419.

[Many thanks to John O’Neill and Constancio del Alamo at The Hispanic Society for their kindness and guidance and to Elizabeth Helm of the National Sculpture Society, for her generosity of spirit.]

[Please stay tuned for PART TWO, in which I will: detail the layout of the show, chronicle critics’ reactions, highlight important sculptural works, and pontificate on the exhibition’s historical influence.]