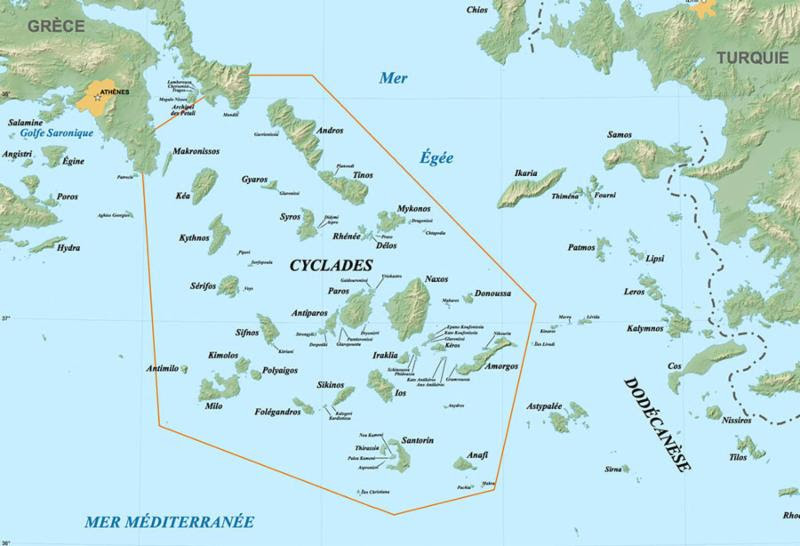

The Cyclades, Part I: From Patmos to Delos

By Barbara Israel

Map: Courtesy Eric Gaba (Sting – fr:Sting), CC BY-SA.3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

When I was invited to go to the Greek islands this summer not a moment passed before I accepted. By boat through the Cyclades!

When I was invited to go to the Greek islands this summer not a moment passed before I accepted. By boat through the Cyclades!

We flew to Bodrum, Turkey (necessitating a brief run for counterfeit handbags), met the boat there, and sailed overnight to the area around Patmos. I had never been to Greece and had no idea what I would see out my window the next morning.

It was Patmos, one of the islands in the chain known as the Dodecanese, the Greek islands just off Turkey named as such for the 12 largest ones. I was on the boat with a group of friends two of whom had relatives on Patmos so off we went to visit them. A car picked us up and I got an early taste of how hilly these islands were. All the main towns seem to be located at the very highest points and Chora, the capital of Patmos, was no exception. I realized later that Patmos was one of the greener islands we visited; many others appeared arid and scrubby. The view down to the harbor was breathtaking with our boat anchored in the distance.

As we ascended the streets became too narrow for a car so we went on foot. Every door had an unusual knocker almost as if the residents were a bit competitive!

Anywhere you turned there was a dreamy view. It reminded me a bit of St. Barts…an international set of people in an idyllic place.

I was on the lookout for ornaments and loved this exaggeratedly tall oil jar that was securely chained to the wall.

I had known that houses in Greece were usually white and blocky in shape but I wanted to know if the roofs were flat for the purpose of collecting water. Though I asked repeatedly, the only response I got was that they were required to look that way. Some of you may know the answer to that….

We first went to the home of a very hospitable family who served us every imaginable Greek hors d’oeuvres in their outdoor living room/terrace under overhanging olive trees. I couldn’t take my eye off the views or the way the outdoor sofas were built into the walls and then piled with cushions.

I loved the old lantern used as a coffee table and naturally, the oil jar. All the houses in Chora abut each other but our hosts told us that the residents have an unwritten rule about no noise or loud music that everyone adheres to….that explains the tranquility of the island. Would that we could implement such an understanding in our fair city!

The next house we visited had an equally amazing view and as night was falling I was able to capture some of the feeling of it.

The next house we visited had an equally amazing view and as night was falling I was able to capture some of the feeling of it.

The boat generally travelled at night so I’d find myself with a new view every day. We had left the Dodecanese islands behind and were now in the Cyclades. I soon learned that historically, the most sacred and central island in this chain was Delos with the other islands swarmed around it, hence the word “cycladic” deriving from the Greek word “kuklos” meaning “circle”. Before this trip I had had no clue as to how important Delos had once been. I was guessing that maybe Delos had been the location of the Delphic Oracle but no that was Delphi! We anchored near Delos and Reneia and went off to the beach for a swim in a small bay.

I had been told that Reneia once had the grim role of being the burial island for the nearby and sacred Delos. Many graves on Delos were excavated and moved to Reneia and the Greeks even had “purification” events at which they evacuated all the pregnant women and dying persons to Reneia. No one was to be born or die on Delos except the gods who could lay claim to the sacred island where Apollo and Athena were born. So Reneia became a “necropolis”, not a sought-after destination spot…but we did find that it had amazing swimming.

I had been told that Reneia once had the grim role of being the burial island for the nearby and sacred Delos. Many graves on Delos were excavated and moved to Reneia and the Greeks even had “purification” events at which they evacuated all the pregnant women and dying persons to Reneia. No one was to be born or die on Delos except the gods who could lay claim to the sacred island where Apollo and Athena were born. So Reneia became a “necropolis”, not a sought-after destination spot…but we did find that it had amazing swimming.

As our boat had approached Reneia I could see masses of stone walls up in the hills and decided to walk there to inspect them closer. On my little hike I saw nothing that resembled graves but the walls were extensive and amazing. The island seemed to be ringed with such walls that I assume had a distinct purpose–perhaps livestock containment or property lines, not graveside markers!

I was naturally very curious to visit Delos the next day and it turned out to be astonishing in the extent of the archaeological site and the legends that explained it. The first view from the boat was interesting at best.

I was naturally very curious to visit Delos the next day and it turned out to be astonishing in the extent of the archaeological site and the legends that explained it. The first view from the boat was interesting at best.

We had a tour guide who gave us an excellent idea of the advanced development that had once been there. From the 9th century BC Delos had become the revered Apollonian sanctuary after it was established that Apollo and Athena had been born there. Zeus was their father and Leto their mother…(no honor among the gods). To this day the lake that they were reputed to have been born in is still known as the “Sacred Lake”. (We didn’t get very close to the Sacred Lake but the palm tree and verdant area are at its edges.) Walking among these ruins as we heard these fables, I confess I half-believed them!

Both a place of pilgrimage for the Greeks and a hugely important commercial port Delos thrived until 88 BC when it was attacked and eventually was abandoned and declined. The excavations we were seeing had begun in 1872 and still continue today.

Both a place of pilgrimage for the Greeks and a hugely important commercial port Delos thrived until 88 BC when it was attacked and eventually was abandoned and declined. The excavations we were seeing had begun in 1872 and still continue today.

We walked through street after street and saw a multitude of houses. One of the grandest and best known houses, recognized particularly for its mosaics, is the “House of Dionysus”. But what fascinated me was the guide’s description of how two marble pots (one depicted at right) collected water that then fed into an underground cistern to preserve water for the use of the family. They were in fact early wellheads that saved water in the same method as the much later medieval Venetians. Also fascinating were the ruins of a system of aqueducts.

The “House of the Trident” was nearby with intact Doric columns two of which sported individual animal sculptures of lions and bulls.

We learned moreover that there had been a 26-foot-high gilded statue of Apollo (in the Archaic kouros form) that had been given to the sanctuary by the people of the nearby island of Naxos. Some fragments of the statue remain. Below, visible as two upright irregular stone forms, are the hips and upper torso (left and right, respectively) of the Naxian Kouros.

We think of our 21st-century lifestyles as so advanced and indeed they are in a multitude of ways, but it is always a surprise to realize that nearly 3000 years ago the Greeks developed a civilization of vast commercial success and artistic refinement, particularly in these islands, as illustrated by the extraordinary ruins on this small island of Delos.

In our January issue of Focal Points, you will receive (without fail) “The Cyclades, Part II: From Shinoussa to Athens with a Stop at Atlantis?”.

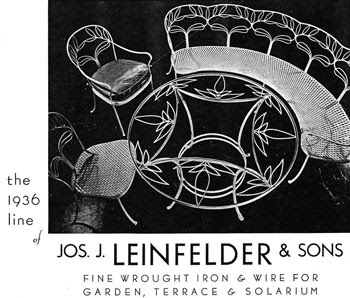

Spotlight on Joseph J. Leinfelder & Sons

Spotlight on Joseph J. Leinfelder & Sons

By Eva Schwartz

One of our favorite garden furniture makers of all time is Joseph J. Leinfelder & Sons, or “Leinfelder”, of La Crosse, Wisconsin. The firm, established in 1908, was an industrial sheet metal business that for one short period (1925-1939) produced an array of imaginative and impeccably stylish wrought-iron furniture.

For years we have had copies of the 1934-1937 and 1939 catalogs in our files, given to Barbara by some collector friends in La Crosse. Other than these documents, we didn’t know much about the company, and never knew why their line of furnishings was so short-lived. Happily, a few months ago we received an email out of the blue from John Leinfelder, grandson of founder Joseph. John was in the process of writing a history of the garden furniture years and was hoping for feedback. I was delighted to hear his stories and to finally learn more about the products we had admired and ruminated on for years. He provided us with the 1933 catalog, which is quite rudimentary in comparison to later publications

Cyril Leinfelder, John’s uncle, was the creative genius behind the furniture line. It was initially a way to increase the profitability of the sheet metal business, but despite an impressive client list–including, R.H. Macy & Co., Neiman & Marcus, Marshall Field, and even the Presidential Palace in Havana–it didn’t particularly pay off financially. Lucky for those of us who love the Leinfelder style, Cyril kept the line going for 14 years, ceasing only when his health forced him to move south. Thumbing through the catalogs, you get a real feel for the whimsy at the heart of this collection, and for the almost perfect balance between traditional and modern design sensibilities. The 1933 catalog notes, “19th-century designs are immense favorites… The trick is to interpret our adaptations of Victorian and French Empire patterns in materials and colors that give lightness and suggest the modern spirit”.

We are thrilled to announce that John Leinfelder has just posted all of the catalogs and his essay on the company’s furniture history at www.lacrossehistory/arts/Leinfelder/index.html. Take the time to peruse the catalogs-they’re bursting with charm!

Several years ago we had the great good fortune to acquire this circa 1936 Leinfelder seat in the “Tree of Life” pattern.

It was an easy sale!

Assembly Required: Two J.W. Fiske Fountains

By Adam Nudd-Homeyer with an Introduction by Eva Schwartz

By Adam Nudd-Homeyer with an Introduction by Eva Schwartz

Since the late 1990s, when Barbara was first doing research on the J.W. Fiske Iron Works, we have been lucky to have a lovely relationship with Joseph Warren Fiske, the affable and sharp-witted great-grandnephew of founder Joseph Winn Fiske (1832-1903). Early on, in preparation for an article she was writing, Barbara had the incomparable treat (for an intrepid researcher) of spending hours in Mr. Fiske’s basement, looking through boxes of 19th-century paperwork and memorabilia. Years later, Mr. Fiske called Barbara when he was ready to sell some Fiske pieces that had remained in the family. Along with a few other pieces, Barbara purchased a pair of zinc and cast-iron fountains with cherub fountainheads and dolphin bases; the only trouble was, they weren’t assembled! These hundred-odd bits and pieces that had sat around for years in Mr. Fiske’s basement, then sat around for a few more in Barbara’s. It wasn’t clear how or when we’d find the time to put them together–especially since we only had one archival photo and two catalog illustrations to go on! Gratefully, Adam Nudd-Homeyer, a restorer, metalworker, historian, and furniture maker, introduced himself to us at just the right time and he turned out to be the exact person for the job. This project took tremendous patience and know-how; and the end result is a pair of beautiful working fountains with a stellar provenance!

Adam’s account:

Over the summer of 2015, I had the pleasure of working with Barbara Israel Garden Antiques on a very special project: the assembly of a pair of identical cast iron and zinc fountains produced by the J.W. Fiske foundry, and known by model as the “Dolphin and Figure Fountain.” One of the most intriguing elements of this project for me was that, as opposed to a repair-restoration project, these fountains remained in “kit form”, having never been assembled with the exception of a very few small sections. In her tome without parallel, Zinc Sculpture in America 1850-1950, Carol Grissom describes this piece in her catalogue (6.26, p. 340) as being sand cast from forty-six patterns, and with the head being slush cast* from a four-section mold.

One of the features of American zinc statuary is that it was often produced as a duplication of another original piece–often European. Such appeared to be the case with this pair of fountains. There was a noticeable difference between the quality of casting on several comparable pieces, most particularly with the tail fins of the dolphins which formed the middle section of the base. Some were very finely detailed, and others, while well-formed, lacked the same sharpness. Indeed, in comparing the more refined pieces to the ones which were presumably recast, the recast pieces duplicated certain identifying marks precisely from the sharper, or original piece. Another sign that the sharper featured ones were from a different casting or maker was that there was an obvious alloying of metals in them–most likely tin or lead–which beaded out upon heating, and was not present in the less refined pieces that were presumably nearly pure zinc. Finally, a smoking gun presented itself identifying the sharper pieces as originals that were recast: the presence still of red casting sand caked in some of the finer details. Also of interest to the production process was that the mold for slush casting the head was also present within the pieces handed over to me–although they appeared to be of cast zinc themselves, as opposed to cast iron–perhaps implying that they, too, were at one point duplicated.

One of the features of American zinc statuary is that it was often produced as a duplication of another original piece–often European. Such appeared to be the case with this pair of fountains. There was a noticeable difference between the quality of casting on several comparable pieces, most particularly with the tail fins of the dolphins which formed the middle section of the base. Some were very finely detailed, and others, while well-formed, lacked the same sharpness. Indeed, in comparing the more refined pieces to the ones which were presumably recast, the recast pieces duplicated certain identifying marks precisely from the sharper, or original piece. Another sign that the sharper featured ones were from a different casting or maker was that there was an obvious alloying of metals in them–most likely tin or lead–which beaded out upon heating, and was not present in the less refined pieces that were presumably nearly pure zinc. Finally, a smoking gun presented itself identifying the sharper pieces as originals that were recast: the presence still of red casting sand caked in some of the finer details. Also of interest to the production process was that the mold for slush casting the head was also present within the pieces handed over to me–although they appeared to be of cast zinc themselves, as opposed to cast iron–perhaps implying that they, too, were at one point duplicated.

Questions of “first cast” and “second cast” became moot, however, when it became apparent that it would be necessary–or should I say, possible–to use the full allotment of pieces to create not just one, but two fountains. As there were not enough original pieces to make an entire fountain from them alone, the choice was made to allocate the pieces by best fit between the two separate fountains, norming them to one another, if you will.

All told, then, Barbara presented me with approximately one hundred pieces of zinc in a few crates, as well as the cast iron basins and bases, when I first arrived to pick up the pieces and begin the project. Although it may sound counter-intuitive, the easiest part is actually figuring out where and how the pieces fit! For those who don’t believe me, I ask them to consider whether a hundred-piece jigsaw puzzle would be very challenging to them. And to that, add that the pieces have depth, texture, and sometimes match marks! I find the best system to be to spread or “unfold” the statue as it fits together on a bench-something quite akin to taking a globe of the Earth and then creating a Assembly Required: Two J.W. Fiske Fountains projection from it. (Note: the frog in the photo on the right is not part of the fountain.)

After this basic layout, the real work begins, soldering each piece to another and letting the form gradually take shape! With nothing other than the fit of each piece to another to guide you, it really is just a matter of deciding on a best reference or starting point and going with it. This project divided itself into two major sections: that of the three-dolphin base, and the boy holding another dolphin. Each provided a separate, reliable reference for a starting point: all of the pieces for the boy, for example, evolved out of a larger single base section. For the dolphin base, the three dolphins mounted to a large cast-iron foundation, which was shaped to look like a rock, complete with mounting holes. Moreover, the dolphins carried at their top the cast-iron basin, cast to look like shells. This in fact gave the dolphin section both a top and a bottom reference.

After this basic layout, the real work begins, soldering each piece to another and letting the form gradually take shape! With nothing other than the fit of each piece to another to guide you, it really is just a matter of deciding on a best reference or starting point and going with it. This project divided itself into two major sections: that of the three-dolphin base, and the boy holding another dolphin. Each provided a separate, reliable reference for a starting point: all of the pieces for the boy, for example, evolved out of a larger single base section. For the dolphin base, the three dolphins mounted to a large cast-iron foundation, which was shaped to look like a rock, complete with mounting holes. Moreover, the dolphins carried at their top the cast-iron basin, cast to look like shells. This in fact gave the dolphin section both a top and a bottom reference.

From there, care only needed to be taken not to over-commit in soldering any one seam until full portions could be assembled “in the round”, showing whether the alignment was coming out properly. Often, serious redressing was necessary to get reasonably well-fitting seams–in large part because the recast sections were often thicker than the originals were. Other times, the zinc had obviously crept out of shape as it sat in boxes for a century or more. Like lead, zinc is semi-plastic at room temperature, and can deform under loading. Using that principle, however, is often the best way to return it to shape, pulling or squeezing the pieces so that the seams line up properly along their full length.

With soldering complete, it is important to test assemble all of the major sections and refit portions that end up looking askew, or in the case of major load bearing members, those which have not come out level or plumb. Once that is done, excess solder is first sloughed off with a hot iron, and then finally filed to shape. One of the benefits of zinc statuary which is soldered as opposed to welded (with zinc) is that even when assembled, the seams retain their original edges and details, and in wiping away the solder and prudently filing, most of these details can remain unscathed in the blending and finishing of the seams–something which is not as easily the case with welding, where original and added material become indistinguishable.

With soldering complete, it is important to test assemble all of the major sections and refit portions that end up looking askew, or in the case of major load bearing members, those which have not come out level or plumb. Once that is done, excess solder is first sloughed off with a hot iron, and then finally filed to shape. One of the benefits of zinc statuary which is soldered as opposed to welded (with zinc) is that even when assembled, the seams retain their original edges and details, and in wiping away the solder and prudently filing, most of these details can remain unscathed in the blending and finishing of the seams–something which is not as easily the case with welding, where original and added material become indistinguishable.

When all was said and done, the pair of fountains took about 140 hours to assemble. With many thanks to research and advice from Barbara’s adroit staff–Eva, Patrick, and Charlie–work went smoothly and was quite enjoyable. It was only upon final delivery that I learned that these pieces had been housed in the home of Fiske’s great-grandnephew! What a special project to be a part of. Thank you, Barbara!

When all was said and done, the pair of fountains took about 140 hours to assemble. With many thanks to research and advice from Barbara’s adroit staff–Eva, Patrick, and Charlie–work went smoothly and was quite enjoyable. It was only upon final delivery that I learned that these pieces had been housed in the home of Fiske’s great-grandnephew! What a special project to be a part of. Thank you, Barbara!

* Grissom describes a slush cast as one, “made by pouring a liquid into negative molds and almost immediately pouring [the] excess out, leaving a layer of zinc metal inside.” (p. 56)

For an interview with Carol Grissom, see the Restoration issue of Focal Points.

On the Research Trail: Curtain-Style Furniture

By Eva Schwartz

In the 18 years I have worked with Barbara, nothing has given me greater satisfaction than doing research and, every so often, solving some mystery or another. Our office is, literally, a library–brimming with books (many of them charming volumes from the late 19th and early 20th centuries), auction catalogs, old periodicals and dozens of trade catalogs that really are of the garden variety. The garden ornament field, while certainly more traveled than it was some decades ago, remains on the fringes of art historical scholarship, blurring the lines, as it does, between fine art and industrial manufacture. It’s not surprising, then, that after all of these years (2015 marks Barbara’s 30th in business!), there’s so much yet to be discovered.

Photos: A. Mininberg

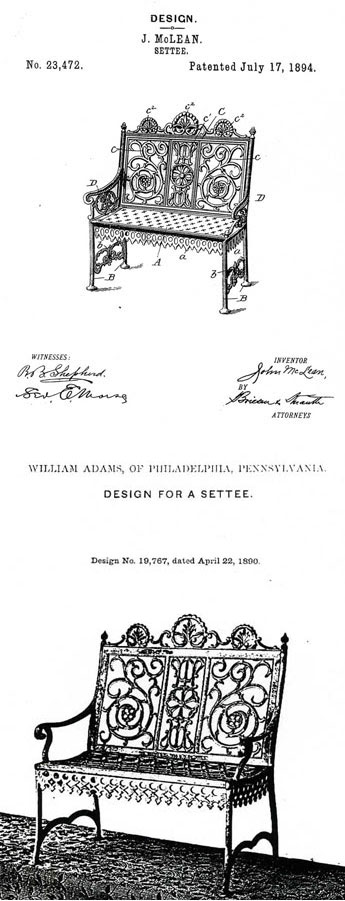

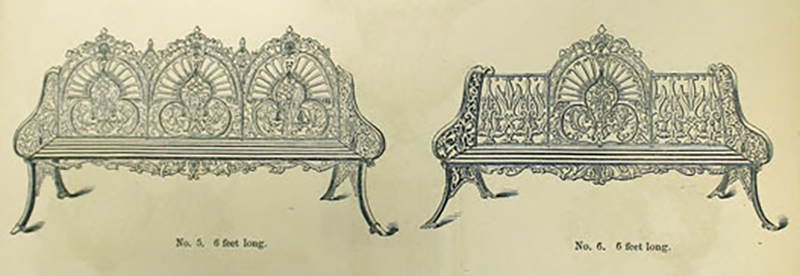

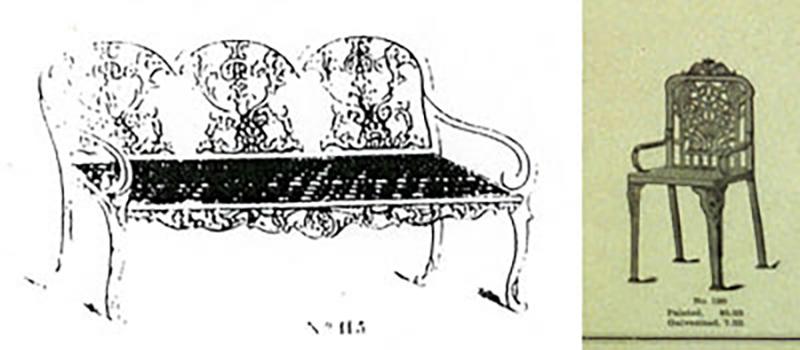

I love getting questions from clients about the history of their objects. Just recently, a client stopped by at an antiques show here in New York, handed me a few photos of her cast-iron furniture, and asked that I shed some light on their design and maker. The photos showed two settees and two armchairs of a uniquely American type known as “curtain-style”. The term “curtain” is used (and was even used in 19th-century catalogs), we think, because the design closely mimics the pattern-dense drapery panels and upholstered furniture of Victorian interiors. These pieces were produced from the late 1880s into the early 20th century, reaching the peak of their popularity in the 1890s. Details and motifs differ from piece to piece, but all curtain-style examples have common characteristics: rectilinear back panels (settee backs are tripartite) containing curvilinear and arabesque patterning; ornamental crests atop back panels; and decorative aprons at the seat edge.

Left – A typical curtain style seat. Right – This variety of curtain-style chair is called “Boston Panel”. Photos: Sylvia Falcón (L); Charles A. Johnson (R)

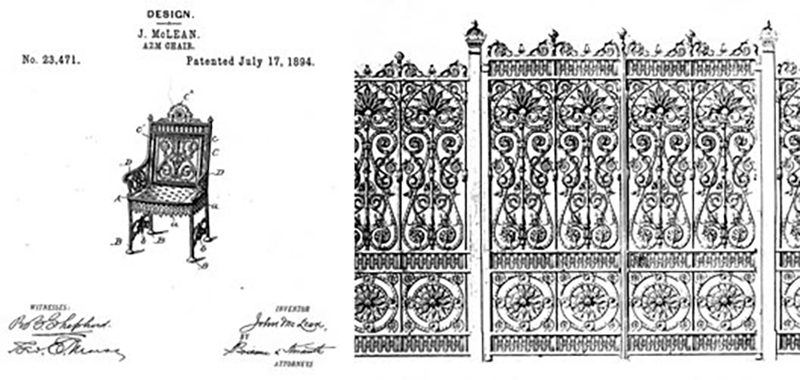

Left – Chair and settee from a typical curtain-style suite. Right – The “Renaissance Chair” in the 1896 catalog of Peter Timmes’ Son (Brooklyn).

Photo: S. Peavey

I expected the task of compiling information on these pieces to be quite straightforward. After all, curtain-style seats were distinctly American, made by a relatively limited number of manufacturers in comparison to European patterns made both here and abroad. Still, attributing our client’s unmarked settees to any one maker would be difficult, as it was my understanding that curtain seat designs were liberally copied and shared. Among these American makers were Chase Brothers of Boston; William Adams & Company and the Hope Iron Foundry, both of Philadelphia; Peter Timmes’ Son of Brooklyn; John McLean, the North American Iron Works, A.B. & W.T. Westervelt, J.W. Fiske Iron Works and J.L. Mott Iron Works, all of New York City; E.T. Barnum Wire and Iron Works of Detroit; and Hinderer’s of New Orleans.

Top – Patent document for John McLean settee, July 17, 1894. Bottom – Patent document for William Adams settee, April 22, 1890.

In our files I found a United States Patent document for a curtain settee issued to John McLean on July 17, 1894. John McLean was a New York maker active in varying machinist/metalworking capacities from 1877 to 1905. Apart from the pattern on the seat, which may be slightly different (it’s hard to decipher this aspect of the design from the patent drawing), our client’s settee is identical to the one patented in 1894. Still, without a mark, I couldn’t categorically attribute the settee to John McLean.

I then found a patent issued to William Adams in 1890. This 1890 document details a settee nearly identical to John McLean’s later patented design, differing only in the arms and stretcher. Digging into our files even further, I found that these were just two patents of several held by different makers for essentially the same settee or chair (each with minor differences). I decided I needed to know more about patents, so I wrote to Michael White, a patent aficionado and the research librarian for the Engineering and Science Library at Queen’s University in Ontario. I’d had a hunch, which he supported, that the patents were filed based on the combination of elements in the design, even if the individual elements weren’t original to the maker. If even one slight change was made to the settee, a new patent could be granted to another maker, which jibed with what I’d seen in the patent documents. I had also been confused as to why some patent terms were longer than others (William Adams’ term was 3.5 years, while John McLean’s was 7 years, and several others were as much as 14 years). Mr. White explained that the patent terms were based on the fees paid; a full term was 14 years, but shorter terms could be had for less money.

These revelations made me question the attribution of our client’s settees even more. For one thing, John McLean’s patent term was a mere seven years, so any foundry could have copied the design once the term expired and the design entered the public domain. Another thing: it’s possible that design-sharing was liberal up to a certain point, at which time makers decided to file individual claims (so the settee could have been made pre-patent). Thus, while the settees could very well have been made by John McLean, we will never know for sure.

Left – Renaissance Revival folding armchair by Edward W. Vaill (1861-1891), ca. 1875. Collection of the Brooklyn Museum (accession #1990.203). Center – Renaissance Revival armchair in the Jedediah Wilcox parlor, 1868-1870. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (accession #68.133.7). Photo: Eva Schwartz. Right – Renaissance Revival side chair, ca. 1875, courtesy AncientPoint.com.

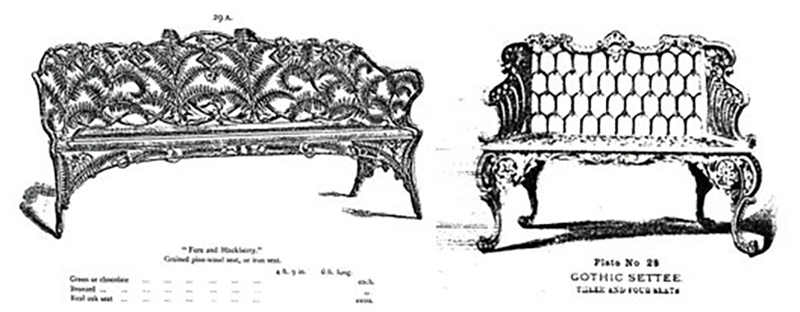

I began to wonder about the origins of the curtain style. American cast-iron makers had mostly copied English, French, and German designs. Curtain style, however, seems to have been an American invention. I grabbed our copy of 19th-Century America, the catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s pivotal 1970 exhibition, looking for insight. [Please note: Although some of the inferences and judgments cast by the show’s cataloguers have since been reevaluated, it remains a tremendously useful document.] The curtain-style settee and chair pictured therein are described as amalgamations of revival styles, drawing mainly from the Renaissance Revival (spanned 1850-1880), but also from the Rococo Revival (1840-1870). Additionally, this genre borrows from exotic Far Eastern styles, seen, for example, in the seat aprons reminiscent of the fringe used on upholstered Moorish-style furniture. The structured, rectilinear quality of the seatbacks, and the ornamental crests are directly related to Renaissance Revival interior furnishings–known for their rectilinear, massive, crested, and notably “masculine” aesthetic. Curtain style, to me, seems a clever melding of masculine and feminine elements: masculine Renaissance Revival form, replete with what might be interpreted as feminine, delicate botanical motifs.

Left – The “Fern and Blackberry” settee, one of many naturalistic patterns in the 1875 catalog of influential cast-iron maker, the Coalbrookdale Company (Shropshire, England). Right – The “Gothic” settee in the 1875 catalog of J.L. Mott Iron Works (New York). This pattern, also called the “Rococo” settee in various makers’ catalogs, was primarily influenced by the Rococo Revival.

The 19th-Century America catalog asserts that curtain-style furniture was first produced in the 1870s, but I have not seen any evidence to support this. In the catalogs we have in our library, cast-iron furniture from the 1850s-70s was predominantly Naturalistic/Botanical and/or Rococo Revival in character (being mainly curvilinear, with plenty of c-scrolls and s-scrolls and having cabriole, or curved, legs), with some Gothic and early Aesthetic Movement (exotic/worldly) elements thrown in. Curiously, the notations in 19th-Century America reference only 1890s trade catalogs (which naturally undercuts the 1870s assertion) with one exception: a Chase Brothers (Boston) catalog from 1859. I must admit getting a bit too excited reading that citation as I wondered how it could be true that the curtain style had appeared at that early date! As we did not have that particular Chase Brothers catalog, I appealed to our good friends at the Winterthur Library.

A settee with tripartite back, a possible early precedent, in the 1859 catalog of Chase Brothers (Boston).

It turned out that the citation referred to two settees that appear on page 20 of that 1859 catalog. The design shown there is identical to one pictured in the 1858 catalog of Wood & Perot (Philadelphia). Yes, these settees could be considered an evolutionary step toward the curtain style, having aprons, crested back panels and intricate foliate patterning. Like curtain settees, these are more related to interior furnishings than most of the other items in the catalog, which are mainly of the Naturalistic variety (fern, grapevine, lily of the valley). Still, I wouldn’t call this design “curtain-style”.

Another quasi-related example is the “Water Plant” seat pattern, registered by The Coalbrookdale Company (England) in 1867, and designed by the celebrated proto-modernist, Christopher Dresser (British, 1834-1904). While this pattern was not a direct model for the curtain style, I will note the dense botanical motifs, boxed in by delineated panels. While the Dresser botanical elements are much more stylized, flattened and linear than the arabesques of the curtain style, the basic form seems to correlate.

Another quasi-related example is the “Water Plant” seat pattern, registered by The Coalbrookdale Company (England) in 1867, and designed by the celebrated proto-modernist, Christopher Dresser (British, 1834-1904). While this pattern was not a direct model for the curtain style, I will note the dense botanical motifs, boxed in by delineated panels. While the Dresser botanical elements are much more stylized, flattened and linear than the arabesques of the curtain style, the basic form seems to correlate.

Left – Patent document for John McLean armchair, July 17, 1894. Right – A fence pattern in the 1875 catalog of Walter McFarlane & Co (Glasgow).

Aesthetically, the curtain style is also strikingly similar to gates and fencing designs produced by British firms like Walter McFarlane & Company (Glasgow) some twenty years before. The settees and chairs bear a similar rigid organizational structure, with many comparable design elements. However, while it can be assumed that many American makers were familiar with European offerings (as shown by the number of copied designs), I can’t prove that they had seen the McFarlane gate patterns.

Left – A settee in the 1858 catalog of Wood & Perot (Philadelphia). Right – An armchair in the ca. 1888 catalog of William Adams & Co. (Philadelphia).

Two patterns from American catalogs seem particularly related to the curtain style. One example, albeit more Rococo than Renaissance inspired, is shown in the Wood & Perot 1858 and 1875 catalogs. This settee with rounded silhouette, scrolled arms, and cabriole legs is reflective of the Rococo Revival furnishings of the period. But it also displays the articulated, partitioned back and dense arabesque patterning associated with the curtain style. Another example, an armchair from the ca. 1888 catalog of William Adams & Co. (Philadelphia), exhibits the arabesques and back crest–but not the Renaissance Revival form–of curtain-style chairs.

Having come across a number of things that seemed connected, but weren’t unequivocal models for the curtain style, I decided I needed to consult outside experts. I first contacted Barry Harwood, the Curator of Decorative Arts at the Brooklyn Museum (and my former professor!). He was convinced that after more searching, I would discover a direct European precedent. So, I wrote to our good friends at Summers Place Auctions in Sussex, England, Rupert van der Werff and James Rylands. As the UK’s top garden ornament specialists, they have seen thousands of objects, and have taught us so much through the years.

James and Rupert expressed what we had always held to be true: that the curtain style was an American invention, reminiscent of interior furnishings styles like the Renaissance Revival. In all their years of looking at objects and catalogs, they had never come across an English, or more broadly, European curtain-style seat. This observation was reiterated by Anna D’Ambrosio, Director of the Museum of Art at the Munson-Williams Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York. She, too, had always understood this style to be American. I checked in also with Sir Neil Cossons, the former Director of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, which oversees the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron in Shropshire, England. He agreed that the curtain style was a distinctly American form. I then contacted Eric Turner, Curator of Metalwork Collections at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and gleaned from him that the V&A did not own any curtain-style furniture. More importantly, Mr. Turner had never come across any European models for the style. So, my question was still unanswered: What would have inspired American designers to suddenly get creative after decades of borrowing European patterns? Curtain style was clearly popular, as so many makers produced a version. Some foundry must have started the trend–but which one?

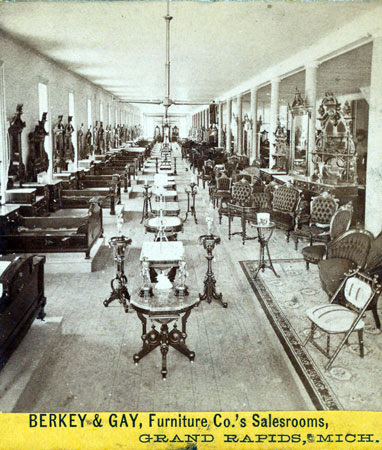

I came up with the (perhaps outlandish) idea that curtain-style furniture originated in the Midwest–in Grand Rapids, or Detroit, Michigan. This is a crazy hunch that I have not substantiated, but nevertheless makes sense to me. The curtain style owes so much to the Renaissance Revival that, in New York City, peaked in the 1860s and 70s; why did curtain furniture crop up and become popular in the 1890s, so many years later? Can we just chalk it up to Victorian eclecticism or was it something more?

View of Renaissance Revival furniture at Berkey & Gay showroom, ca. 1880-1890, Grand Rapids, MI. Photo: Schuyler C. Baldwin, via Wikimedia Commons.

It turns out that the handcrafted furniture companies of the East Coast had given way to the mechanized furniture factories of the Midwest. By the 1880s, Grand Rapids furniture makers like Berkey & Gay, Nelson Matter, and Phoenix kept East Coast hotels and restaurants stocked with furniture, becoming the most prolific every-day furniture suppliers in the country. In the 1880s and 90s, they were primarily known for Renaissance Revival bedroom and lobby suites. Is it possible that these Midwest furniture makers brought a second wave of Renaissance Revival to New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and beyond? Did this influx inspire some East Coast foundry to create the curtain style? Or did the curtain style get its start in the Midwest, where in the 1890s Renaissance Revival was king? I haven’t yet solved this conundrum, but I feel like I’m getting there. If any of our astute readers have insight or access to lesser-known catalogs, please do contact me at eva@bi-gardenantiques.com.

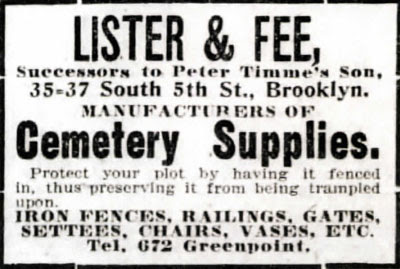

Top – Detail of Lister & Fee mark.

Bottom – Lister & Fee advertisement in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 6, 1907, p. 12.

Gratefully, one little puzzle relating to our client’s curtain-style furniture had a most rewarding payoff. While the settees were unmarked (making their attribution to John McLean debatable), the armchairs bore the mark, “Lister & Fee Brooklyn NY”. We had never heard of the firm, and had always associated the chairs’ design with another Brooklyn-based manufacturer, Peter Timmes’ Son. I had loads of fun searching online newspaper archives for some mention of Lister & Fee [the sheer quality of the writing in 19th-century periodicals delights me to no end!]. Most references were to the renowned Joseph Lister (1827-1912), of Listerine fame, but one tiny advertisement in the November 16, 1907 edition of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle solved the mystery.

While we’ve learned a great deal about cast-iron makers through City Directories, they certainly don’t tell the whole story. The last City Directory entry relating to Peter Timmes’ Son appeared in 1902–for a firm called Timmes & Hecht, which we understood to be the last incarnation of the Timmes company. The 1907 ad for Lister & Fee proclaims that Lister & Fee were “successors to Peter Timmes’ Son”, implying they either took over the concern or bought the rights to some of their patterns. This revelation explained why the Lister & Fee name was on the quintessential Peter Timmes chair! Here’s hoping that further curtain-style discoveries are forthcoming.