Restoration: How Much is Too Much?

By Barbara Israel

Because we are working with outdoor objects we almost always anticipate having to do some sort of restoration. Subjected to every conceivable weather condition, garden ornament takes a beating that few others endure. The problems can be as simple as a few chips or as serious as the loss of a major part. Often weathering produces a positive effect on the appearance of statues. In certain cases, such as that of a fine art bronze, surface weathering can have disastrous effects.

The question I’m most commonly asked is about maintenance of the surface of cast-iron objects. Because iron is subject to rust and corrosion its surfaces demand particular attention. In almost every situation these objects were meant to be painted. And painted frequently. When an 1870 statue in Martha’s Vineyard was being restored a paint analysis was done of the finish. Over the years it had acquired 20 or so coats of paint. So, if a seller tells you that a cast-iron piece has its “original” surface you have every right to question that information. If a cast-iron piece doesn’t have a fairly thick buildup of paint it may be a reproduction, it may have been “skinned” by sandblasting or chemically stripped of paint. The scenario of it having been indoors for its life is unlikely. The irregular surface created by the years of repainting is often very pleasing. We recommend wire brushing the flaking paint, but stopping short of stripping the piece. In some cases the paint buildup will have obscured the detail and then you have little choice but to strip off the paint. We like to research which colors are historically accurate and restore the finish appropriately. In place of sandblasting we recommend other technologies such as soda-blasting or powerwashing. Powder coating has become popular recently but should only be used on furniture that is in everyday use.

What about remaking missing parts? First, we evaluate whether the piece is a good candidate for serious and possibly expensive restoration. Then we search for the original design in our trade catalogues or for old photographs of an identical object. If we find it we can follow the illustration and have a replacement part re-created. We may actually take an old restoration apart if it has been poorly done or glued with epoxy. It will be disassembled and restored with appropriate materials. With restorations as major as these we would always recommend consulting a conservator.

A few years ago, we had a dramatic example of such a situation when the butterfly (Psyche) on an Amour (Cupid) statue went missing at an antique show. After extensive outreach to the antiques world we were stymied. Luckily, we had excellent photos of the butterfly. Charles Johnson, our in-house conservator, created a perfect replica in plasticine from which he cast a plaster model. That small item was then carefully taken to a foundry where it was re-cast in vintage 19th-century cast iron. The photo sequence above shows the statue, a detail of the butterfly and the re-sculpted plasticine butterfly.

A few years ago, we had a dramatic example of such a situation when the butterfly (Psyche) on an Amour (Cupid) statue went missing at an antique show. After extensive outreach to the antiques world we were stymied. Luckily, we had excellent photos of the butterfly. Charles Johnson, our in-house conservator, created a perfect replica in plasticine from which he cast a plaster model. That small item was then carefully taken to a foundry where it was re-cast in vintage 19th-century cast iron. The photo sequence above shows the statue, a detail of the butterfly and the re-sculpted plasticine butterfly.

So where does one draw the line? When a piece has lost an important part or the loss is extensive–such as a figure missing a significant portion of its face–then we would generally choose not to restore and in most cases would not even buy such an object. In the particular case of cast iron or zinc, the cost of producing a mold can be prohibitive. Even with an illustration as a guide, it may be an ill-advised use of resources to attempt restoration, as it may not necessarily increase the intrinsic value of the object. However, there are examples where restoration is appropriate. For instance, an urn we acquired was missing an ear on one of its rams head handles (right). Because we could take a mold from the other handle, and thus duplicate the original, it made sense to effect the repair.

So where does one draw the line? When a piece has lost an important part or the loss is extensive–such as a figure missing a significant portion of its face–then we would generally choose not to restore and in most cases would not even buy such an object. In the particular case of cast iron or zinc, the cost of producing a mold can be prohibitive. Even with an illustration as a guide, it may be an ill-advised use of resources to attempt restoration, as it may not necessarily increase the intrinsic value of the object. However, there are examples where restoration is appropriate. For instance, an urn we acquired was missing an ear on one of its rams head handles (right). Because we could take a mold from the other handle, and thus duplicate the original, it made sense to effect the repair.

Well-executed restoration combined with responsible conservation enhances the beauty and longevity of the antique and adds to the future value and enjoyment of the object.

Reveries from Running Duck Farm

Reveries from Running Duck Farm

By Nan Zander

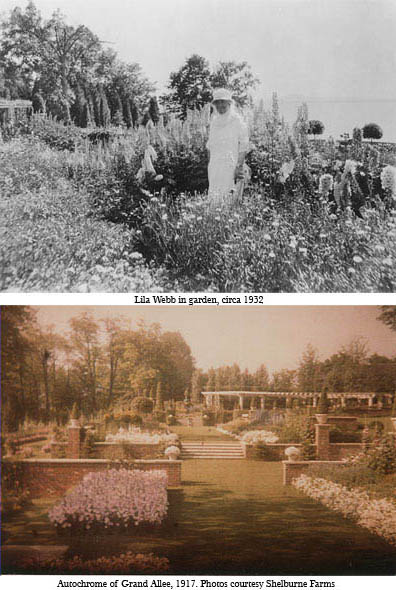

Shelburne Farms was once a breathtakingly beautiful model farm on Lake Champlain where first families of the Gilded Age summered. Today, Shelburne Farms is a 1,400-acre National Historic Landmark lovingly restored and operated as an educational non-profit. Begun in 1886, Shelburne Farms was the brainchild of Dr. William Seward and Lila Vanderbilt Webb, brought to fruition with the help of Frederick Law Olmsted and architect Robert H. Robertson. At its peak, Shelburne employed 300 workers to carry out and maintain the Webbs’ vision of a working farm. The operation eventually outgrew itself and became unsustainable, and over the years nature began to take over the buildings and grounds. In 1972 the current non-profit came into being, and in the 1980s restoration began. (Much of the architectural renovation of the gardens is still under way as part of a four-phase plan, the details of which are available on the Shelburne Farms website.) Restoration of the walls and steps of the Grand Allee began in 1981, and historical research on its plantings began a year later. In 1984, the actual plantings were meticulously restored or replaced. While much of the renovation on the Farm continues, the Grand Allee once again reflects Lila Webb’s horticultural vision.

When Lila Vanderbilt Webb began working on her gardens at the end of the nineteenth century she was inspired by the European gardens she had seen on her travels abroad. Archival records and photographs from the period show the evolution of Lila’s gardens. She continued to perfect her gardens until the 1920s, but photos of the time show them in a more or less final state by 1912. The Grand Allee was a naturalistic border full of interesting color progressions in the then current English taste. Gertrude Jekyll was the most famous English garden writer and designer of Lila’s time and, while there is no evidence that Lila Webb ever met her when she traveled to England, Lila would have been very aware of the prevailing taste. Lila’s head gardener was English and was another important influence on what went into her gardens. The Shelburne Farms archives contain numerous heavily marked copies of Jekyll’s writings as well as Lila’s Webb’s original list of plant material. Lila’s library of garden books was extensive and we know that she looked to other contemporary publications of the day as well, including Charles Platt’s Italian Gardens (1944), Edith Wharton’s Italian Villas and their Gardens (1904), Charles Latham’s The Gardens of Italy (1905) and Gertrude Jekyll publications such as Wall and Water Gardens (1901). The original plantings have mostly disappeared by the 1960s, so restoration of the plantings has been based to a large extent on this archived information.

When Lila Vanderbilt Webb began working on her gardens at the end of the nineteenth century she was inspired by the European gardens she had seen on her travels abroad. Archival records and photographs from the period show the evolution of Lila’s gardens. She continued to perfect her gardens until the 1920s, but photos of the time show them in a more or less final state by 1912. The Grand Allee was a naturalistic border full of interesting color progressions in the then current English taste. Gertrude Jekyll was the most famous English garden writer and designer of Lila’s time and, while there is no evidence that Lila Webb ever met her when she traveled to England, Lila would have been very aware of the prevailing taste. Lila’s head gardener was English and was another important influence on what went into her gardens. The Shelburne Farms archives contain numerous heavily marked copies of Jekyll’s writings as well as Lila’s Webb’s original list of plant material. Lila’s library of garden books was extensive and we know that she looked to other contemporary publications of the day as well, including Charles Platt’s Italian Gardens (1944), Edith Wharton’s Italian Villas and their Gardens (1904), Charles Latham’s The Gardens of Italy (1905) and Gertrude Jekyll publications such as Wall and Water Gardens (1901). The original plantings have mostly disappeared by the 1960s, so restoration of the plantings has been based to a large extent on this archived information.

In my mind, one of the most interesting aspects of this garden restoration is how the essence of the early twentieth century garden has been kept using present day material. The overall impression a garden leaves, the “spirit” of a place, can be due to many different things. In the case of the Shelburne Farms garden, color is the feature that brings Lila Webb’s hand into the present scheme. The Grand Allee is 76 feet long, laid out as it was in Lila’s time with luminous cool colors on the north and south ends, intensifying to the more dramatic yellows, oranges and reds at mid-border. It gets full sun all day, and is in USDA hardiness zone 5. The earliest blooms emerge in early June and the show continues for five months. The garden reaches its peak during mid-June and early July and the Gertrude Jekyll-influence color scheme is at its most dramatic.

In my mind, one of the most interesting aspects of this garden restoration is how the essence of the early twentieth century garden has been kept using present day material. The overall impression a garden leaves, the “spirit” of a place, can be due to many different things. In the case of the Shelburne Farms garden, color is the feature that brings Lila Webb’s hand into the present scheme. The Grand Allee is 76 feet long, laid out as it was in Lila’s time with luminous cool colors on the north and south ends, intensifying to the more dramatic yellows, oranges and reds at mid-border. It gets full sun all day, and is in USDA hardiness zone 5. The earliest blooms emerge in early June and the show continues for five months. The garden reaches its peak during mid-June and early July and the Gertrude Jekyll-influence color scheme is at its most dramatic.

Miss Jekyll believed the Delphinium had the “grandest blues of the flower year” and so naturally they have been in the Grand Allee since its beginning. No surprise it was also the plant that Lila Webb was the most proud of. Today, the magnificent Delphinium elatum “Pagan Purples” reach over four feet tall in the blue, white and pink ends of the garden. These New Millenium hybrids are an improvement in many ways to the delphiniums of Lila’s day. It is interesting that Gertrude Jekyll used to grow Delphiniums successfully from seed, which many gardeners find quite difficult nowadays as seeds collected from hybrids will not grow true, if at all, and even if seeds are acquired from a proper seed source they have very specific germination needs. In the archives at Shelburne Farms is a note from Lila Webb to her Farm Manager Edward F. Gebhardt that “…pyrethrum (painted daisy) a good thing to take place of Delphinium”. I suppose this could also be a reference to replacing the delphiniums after they bloomed with a new bloomer, but it could also be a reference to replacing the rather short-lived perennial. In either case, how nice to care so deeply about your garden and have the means to have it exactly as you please. The Delphinium bloom just after the Siberian Irises “Caesar’s Brother” and “Great White Heron” and the Oriental poppies, which include “Goliath” in the hot, middle section and “Helen Elizabeth” among the cool pinks and blues. The Delphinium bloom coincides with the Oriental and Asiastic lilies, which put on a magnificent show of their own.

On July 23, 1926, Lila Webb noted in her diary that “more than 350 people came to see the garden this afternoon in response to our invitation issued through the newspaper. It looks very well. The lilies are superb.” The lilies look just as superb today. The Asiatic lilies in the hot color range include the Gran Cru which is an intense yellow with red centers and Cancun, which is a more exotic looking deep yellow with reddish-orange tips. A standout in the cool section is the Oriental Lilium Casa Blanca, which many gardeners feel is the finest white lily ever. It can reach four feet in height, has huge, glowing white flowers borne in multiples on sturdy stems and an intense fragrance. Being a modern lily, it was not in Lila’s garden but certainly other white lilies were.

While the main restoration of the plantings in the Grand Allee has been completed, like most gardens it is constantly getting refined and replanted. Recently a group of Plume Poppy Macleaya cordata was removed from the Grand Allee. It had been planted after Lila’s time and, while reliable for foliage, has very little color to contribute to the garden scheme. In its place Hydrangea trees were planted at intervals at the back of the borders. Both Lila and Gertrude Jekyll loved hydrangea–after all who doesn’t?–and so in a sense the garden took one step back to historical accuracy. What’s more, the gardens at Shelburne Farms sit on a 1,400-acre site devoid of any protection from vermin. As a gardener in suburban New York I marvel at the talk of lilies and hydrangeas that need no protection from deer. Shelburne Farms has no deer problem–its roses, lupins, dahlias, columbines, phlox and all its other myriad perennials, annuals and bulbs bloom in a paradise free of voracious marauders.

To see the Shelburne Farms gardens in all their glory, you can visit them from the middle of May until the 3rd week in October. Tours of the gardens are given approximately five times a day. Special tours are also available. For more information please visit Shelburne Farms website at www.shelburnefarms.org.

An Interview with Carol Grissom: Author and Expert on Zinc Statuary

By Katy Keiffer

In her encyclopedic book Zinc Sculpture in America: 1850 – 1950 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2009), Smithsonian conservator and historian Carol Grissom has created the most complete catalogue of this popular art form to date. The great achievement of this 614-page study lies in its treasure trove of photographs of zinc sculpture and ornament from throughout the US, most taken by the author, accompanied by detailed descriptions and information on the foundries that produced these pieces. Grissom has organized this vast catalogue of objects according to form or function: animals, fountains, religious figures, civic monuments, tomb ornament, famous people, trade figures and Indians.

Inexpensive and relatively easy to produce, zinc sculpture became a significant part of the American landscape in the mid-19th century, whether atop a fountain, commemorating a war, ornamenting a building or advertising a trade. As zinc has disappeared from view, Zinc Sculpture in America provides the means to renew our interest and appreciation of this art form.

Focal Points spoke with Carol Grissom about her book and how the project came to fruition.

FP: What got you started on this project? Did you have any idea it would become so huge?

CG: It started with a statue of the Ohio 4th Regiment at Gettysburg. I saw this monument around 1979 and wondered what on earth it was made of! Curiously the very same year that this monument was erected, the Gettysburg Board of Commissioners issued guidelines stating that bronze statuary had to be in “real” bronze, as opposed to the “White Bronze” as one type of zinc monument was called. This happened at many cemeteries such as Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, but others like Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn still have many zinc monuments.

Shortly thereafter I got a grant to do research, having discovered that there was almost nothing written on the subject. I began collecting material and wrote a few papers. Soon people were calling me for information. In 2002 I got a second grant from the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art, working with a recent German PhD who had written her thesis on zinc sculpture made in Berlin. We were able to document many pieces in Europe that appeared to be identical to statues in the US. Though I was only able to evaluate one pair in person; one piece had a German mark and the other an American, otherwise they were identical in every way.

Eventually Barbara Israel and I hypothesized that some of the bigger cast iron foundries in the US, such as J. L. Mott Iron Works, had gone to Germany and bought many examples of different statues. Then, by melting off the solder joining the pieces, it was possible to sand cast the various component parts. When the new castings were put together, the companies could offer the statues for sale to a broad market in the United States. For example, Barbara [had] a Newfoundland dog in her inventory with a German mark, but it was identical to dogs in some of the better known American catalogues for zinc.

Eventually Barbara Israel and I hypothesized that some of the bigger cast iron foundries in the US, such as J. L. Mott Iron Works, had gone to Germany and bought many examples of different statues. Then, by melting off the solder joining the pieces, it was possible to sand cast the various component parts. When the new castings were put together, the companies could offer the statues for sale to a broad market in the United States. For example, Barbara [had] a Newfoundland dog in her inventory with a German mark, but it was identical to dogs in some of the better known American catalogues for zinc.

FP: How did you find all the material for your extensive catalogue? It’s so complete!

CG: What really helped me was the incredible organization Save Outdoor Sculpture or SOS! This is a volunteer organization that with a little seed money from the US government was able to start compiling a database of outdoor sculpture and monuments around the county. Records are now housed at the Smithsonian Institution, and people are still adding to it. The database is available to the public at this URL: http://www.heritagepreservation.org/Programs/Sos/finding.html. Altogether there are over 400,000 images of paintings and sculpture assembled in the database, with roughly 40,000 being devoted to outdoor sculpture.

Actually Saving Outdoor Sculpture was so active that I often had to call a local source to be sure that the piece I was interested in photographing was not undergoing restoration! I had several experiences of going to a particular location only to find that the sculpture was missing from its site and undergoing repair.

Another development that had a huge impact on my research was the rise of the internet as a search tool. Suddenly I had access to many images and websites documenting town histories and their monuments. This was not available when I started this project about 20 years ago. You can imagine that my format changed considerably once I gained access to those records.

FP: You took many of the photographs in the book. How did you research the objects once you found them?

CG: Often through town libraries and historical societies. Usually I would try the library first, since I found that librarians were a great help in this quest. Nearly all of them have a real interest in their town’s history, and they were an invaluable aspect of my research.

FP: Did US foundries such as J. L. Mott and J. W. Fiske cast zinc as well as iron?

CG: No, it doesn’t seem so. Making sculptures may have been too fiddly for the big iron producers. While Mott and Fiske would cast the iron basins and structures for fountains, for example, they seem to have purchased the zinc statues for their fountains from Moritz J. Seelig, who had been trained as a sculptor before his immigration to the U.S. Seelig would then attach a plaque attributing the statue to whichever foundry had commissioned him, J. W. Fiske, J. L. Mott, William Demuth and others.

FP: In this issue of Focal Points, we recount the search for a long lost monument in Babylon, NY, which led to you. Are you often approached by people seeking information on their town history and its monuments?

CG: All the time! Mostly they hear of me by “googling” zinc sculpture. A few of the papers that I had written on the subject will pop up right away, leading them to me. Of course, the more research I did on outdoor monuments and zinc, the more I became a resource for others. But, they became a resource for MY work, and I learned about pieces I would never have found on my own without their questions. It was a very satisfying aspect of the project.

FP: What happened to zinc? Why did it fall out of favor?

CG: Mainly it just plain went out of style. Municipalities and buildings moved into the Art Deco style of ornament, and statues were no longer being commissioned to adorn buildings. Though J. W. Fiske kept zinc statuary in their catalogue until 1956, the incredible vogue it had enjoyed in the last quarter of the 19th century was long over.

FP: As a conservator, can you speak about the restoration of zinc? Does it come with special challenges?

CG: There is no question that zinc is very difficult to restore. It is very brittle and because it is often very thin, it can be extremely fragile. It isn’t easy to solder on new pieces. In any case, as a conservator, I prefer that companies use epoxy or some other product so that repairs are easily spotted by someone like me. Since zinc is so often painted, those repairs would not be obvious to anyone else. Methods of repair are very dependent on what has been broken. There is a conservation company called McKay-Lodge in Ohio with a metals specialist and sculptural conservator named Tom Podnar who does zinc restoration very successfully.

Sometimes, if a military statue is being repaired, the restorer will actually acquire buttons or other hardware from original uniforms and solder those on. Or they might take a mold from an original backpack or gun, and cast that. The military demands historically accurate restoration, for the obvious reasons, as well as not wanting to hear about it from re-enactors and history buffs.

There are also foundries that will replace zinc with cast aluminum. Though it is hard to spot the difference initially, aluminum will corrode if the piece is installed on a fountain, and repeatedly splashed with chlorinated water. As a result, though aluminum can look good, it does not have a long life, and therefore is probably not an economical solution to replacing lost or broken statuary.

FP: Do you think that zinc statuary will remain an “antique” collectible given that no one is using this material now? Or do you foresee a renaissance of the medium?

CG: I don’t see a renaissance in zinc as a sculptural medium, although there has been something of a renaissance recently in the use of sheet zinc for cladding buildings–for a sort of industrial look. As time passes and zinc statuary becomes increasingly rare, however, I can only imagine that its value will go up.

The Women’s Exchange Fountain, Babylon Village, Long Island, NY

By Katy Keiffer

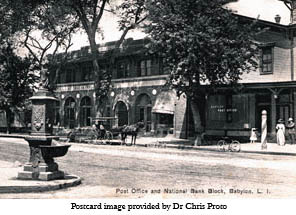

Across the United States are thousands of small towns that once boasted a village square with a fountain or statue to mark it. As Americans have moved away from the village center and out to the suburbs, many of these historic monuments have been lost, vandalized or demolished, much to the dismay of those residents who cherish this link to a town’s history. Babylon Village, Long Island, is one such community that is anxious to restore their monument. Encouraged by one of his dental patients, Dr. Christopher Proto has taken on the task of identifying and recovering the beautiful cast-iron fountain and accompanying zinc statue erected in Babylon in 1897 by the Women’s Exchange. Chris has been leading the search for the original manufacturer’s designs in order to commission a new incarnation.

The Women’s Exchange was a program established in the 19th century to aid women, typically rather more genteel women, who found themselves in reduced circumstances either through the loss of their spouse or through economic ill fortune. Working in a factory wasn’t an option for many of these women who needed to be home in order to care for their families. The Exchange provided a place for these women to sell their high quality goods at a competitive price, keeping a portion of the sale for operating expenses. “Consignors” remained anonymous so as to preserve their reputations.*

The Women’s Exchange in Babylon functioned between 1889 and 1897 when they closed their storefront due to declining sales. With $400 remaining in their treasury, they decided to purchase a fountain and statue to commemorate their good works in the village. It was dedicated on Memorial Day, 1897. Whether through an accident or vandalism, the statue gracing the top of the fountain was damaged. By 1917 its fate was sealed as the state health department outlawed the use of public drinking fountains and the whole structure was removed.

There are some elderly townsfolk who insist that a number of prominent citizens, as children, were involved in a prank–removing the statue (or some of its parts) and throwing it in the creek. In the 1970s, a local resident and his father dove in the creek to recover the statue or any fragments, but were unsuccessful. There are plans to mount another diving expedition in the coming months. Another story suggests that the fountain was hit by a trolley which toppled the statue. According to Chris, there are still a couple of years’ worth of newspaper microfilm to pore through and, perhaps, one of these stories can be corroborated.

Guided by a couple of blurry photos, Chris’ patient, the instigator of this quest, turned first to eBay and quickly discovered a fountain ad resembling the Babylon model manufactured by a Milwaukee company called Rundle Spence. He contacted the company and was directed to David Spence, a fifth generation scion of the family. Spence delighted in the quest and sent a 1915 original catalogue with a fountain model that was very close in design.

Sometime later, the same patient tracked down a photo of the Myers Drinking Fountain, installed in a park in Savannah, GA. Atop this fountain was the exact same statue–a maiden holding a dove–as the Babylon Women’s Exchange Fountain; however, the design of the cast-iron fountain was different. Picking up the thread, Chris approached the Savannah Parks Department and found that their fountain was installed at around the same time as the one in Babylon. The Parks Department sent Chris a newspaper article about the installation and there he learned about J. W. Fiske, one of America’s pre-eminent companies of the time. In searching J. W. Fiske online Chris happened upon the work of Smithsonian curator Carol Grissom, whose new book is highlighted above.

Carol sent Chris some pages of her book that depicted a nearly identical fountain still in existence! Chris contacted Paul Fry of the Ligonier, PA Department of Public Works, who was extremely knowledgeable and helpful. The statue atop their fountain was damaged by a snowplow in 2003, but they were able to have it restored at the Stewart Ironworks in Covington, KY. Scott Wall at Stewart researched the restoration. In fact, he and Chris discovered photos of the restoration on the company’s website. “Everyone I have spoken to has been so helpful! I can’t get over how nice people have been!”, Chris raved as he described his odyssey. Carol Grissom’s work also directed him to another example with an identical statue installed in Court House Square, Harrisonburg, VA. Sadly, the statue had been vandalized and was removed, but the fountain is still sitting in front of the courthouse. Plans are now underway to have the statue restored.

It was at this point that Carol Grissom referred Chris to Barbara Israel. She recommended he read Barbara’s article on the Fiske and Mott companies that appeared in The Magazine Antiques in March 2000. Chris explained his quest in an email to our office. We didn’t seem to have anything in our files that exactly matched his description or the photo he sent us. Several weeks later while reviewing files of objects sent in for research (in conjunction with this issue of Focal Points), our chief researcher and archivist, Eva Schwartz, stumbled across a photo sent to us eight years earlier by the Anacortes Museum in Washington State. With something of a shock Eva realized that the Anacortes statue and the one from Babylon were identical.

Eva conveyed this news to Chris, and he excitedly phoned up the museum. An extremely helpful and friendly Judy Hakins at the Anacortes Museum sent him 27 photos of their fountain which had recently been restored. Although the fountain was slightly different, the cast-iron panels were identical and in excellent shape. Helping people like Chris is one of the great joys our business affords us. Chris did an enormous amount of sleuthing that led him from one city to another looking for a piece to use as a model for the long lost fountain of Babylon. As Chris said of his quest, “You hit so many dead ends and you keep turning corners which lead you to something or someone else. Eventually, you find what you need.”

Eva conveyed this news to Chris, and he excitedly phoned up the museum. An extremely helpful and friendly Judy Hakins at the Anacortes Museum sent him 27 photos of their fountain which had recently been restored. Although the fountain was slightly different, the cast-iron panels were identical and in excellent shape. Helping people like Chris is one of the great joys our business affords us. Chris did an enormous amount of sleuthing that led him from one city to another looking for a piece to use as a model for the long lost fountain of Babylon. As Chris said of his quest, “You hit so many dead ends and you keep turning corners which lead you to something or someone else. Eventually, you find what you need.”

At this point Chris and his committee are looking at different ways to create a new mold from the Ligonier fountain, and are soliciting bids from several foundries to cast the piece anew. Eventually the new version of this old monument will be placed in front of the old village library, now the headquarters of the Babylon Village Historical Society. The village plans to plumb the fountain but it will not be used as a drinking fountain for dogs, horses and people as was the original. Instead it will serve as a monument, not only to the good women of the Exchange, but also to the tireless efforts of the Historic Fountain Committee, local government and the various civic groups and individuals who have committed time, talent and funds to the project.

*More information about the Women’s Exchange programs can be found in Kathleen Waters Sander’s book, The Business of Charity: The Woman’s Exchange Movement, 1832-1900 (University of Illinois Press, 1998).

__________________

We have an exciting next issue planned that will highlight the 19th-century wildlife sculptor Edward Kemeys (1843-1907) and many of the lesser know sculptures of Central Park. For example, my personal favorite, the Paul Manship gates at 84th and Fifth Avenue.