A Visit to the Untermyer Gardens

by Barbara Israel

Last July 17th, one of the hottest days of a very hot summer, I took three of my employees on a road trip to see the progress of the restoration to the Untermyer Gardens. To get there we wended our way through the backstreets of Yonkers, New York. You don’t generally expect to find an estate of this grandeur in the middle of a suburban neighborhood, so it is quite surprising when you arrive at the relatively discreet entrance. We pulled into a parking lot that appeared to belong to a school convinced we had made a wrong turn. As we emerged from air-conditioned comfort into the heat and humidity of midday we were greeted by our guide, Timothy Tilghman, who was wearing a very distinctive and useful (on such a day) straw hat.

Timothy did not seem at all affected by the heat; indeed, he was brimming with enthusiasm. He told us he is the sole horticulturalist (and only full-time employee) working in the garden. As he talked, we walked, and I began to look past him and focus on the looming, crenellated wall over his shoulder.

He began the remarkable story of the Untermyer Gardens. During Samuel Untermyer’s years at the property, 1899-1940, the gardens had been some of the most impressive anywhere. After his death, however, this gem of a property had been allowed to fall into a state of utter decay. As Timothy’s tale unwound I became quite impatient to walk through the doorway and see what lay beyond. I kept sneaking peeks and was intrigued by what I was seeing. In the meantime we were being told that the gardens used to be around 150 acres and had had 60 greenhouses and 60 employees. Today, it was pared down to a mere 43 acres, a number that sounded like more than enough to restore and maintain! We asked where Mr. Untermyer had lived on the property and Timothy explained that his house “Greystone” had been demolished in 1948.

There was an interesting competitive aspect to the Untermyer history. Evidently, after Mr. Untermyer had seen John D. Rockefeller’s garden at Kykuit in Pocantico Hills, New York, he declared that he would build the largest, grandest, and the most spectacular garden in the world. He went so far as to hire the same architect, William Welles Bosworth, who had created the house and garden at JDR’s. (See our Special Gardens issue of Focal Points to read about the Japanese Garden at Kykuit). Bosworth’s plans were begun in 1912 and Untermyer lived until 1940 so he had plenty of time to fulfill his dream. The scale of what we were about to see began to dawn on me when at last Timothy ushered us through the door.

My goodness! …we went through a Mycenaean gate and into an Indo-Persian garden of such splendor that I questioned if I’d just slipped into a dream. This garden, officially called the Walled Garden, shows a myriad of stylistic influences. Reflecting pools, an amphitheatre, statues by Paul Manship, and porticoes that stretched wide and far. (Photo: Jonathan Wallen, courtesy of the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy)

The whole was symmetrical with intersecting axial pathways in the most formal possible design. One of the most impressive features of the garden is the classical marble rotunda, crafted of Alabama marble.

The whole was symmetrical with intersecting axial pathways in the most formal possible design. One of the most impressive features of the garden is the classical marble rotunda, crafted of Alabama marble.

The Greek rotunda overlooked a vista to the Hudson River (below) that seemed to launch us into another part of the world, the Mediterranean. Bosworth had exploited one of the greatest views in America for its location. As I looked closer I noticed the beautiful mosaics on the floors and in the pool below the rotunda. Moreover, the walls and balustrades used to connect the two levels of the Greek Garden are worth noting–Bosworth used repeating geometric motifs to make the whole space feel cohesive. (Fish mosaic photo: Jonathan Wallen, courtesy the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy)

We were guided to the left of the central amphitheater to the top of an enormous stairway that appeared to lead right down to the edge of the Hudson and a view of the Palisades. Timothy explained that Bosworth had copied The Vista, as these stairs are called, almost exactly from the Italian Renaissance Villa D’Este view down to Lake Como. Large trees and second growth have since obstructed a large part of the original view. Along this stepped walkway there had been six parallel color gardens each showing a single color of flower. On our visit, there was little or nothing left of them but you could distinguish some general shapes and outlines. (Vintage photo of The Vista Steps courtesy of the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy)

“Overgrown” does not fully convey how far gone the gardens were. I suddenly pictured myself giving up my daily life and spending it digging and discovering hidden treasures in this wilderness of weeds! Sanity soon returned when Timothy explained that because the City of Yonkers owns the gardens that only union labor was permitted!

We continued down the steps wondering the entire time if we were going to be sweating back up them on the return journey. The steps terminated in a circular overlook with a pair of tall ancient marble columns that purportedly came from Stanford White’s collection. (For more on Stanford White see the Hurstmont Planter article in our Marble in America issue of Focal Points.) These early examples are some of the few remaining ornaments on the property as the majority were sold off at an auction soon after Untermyer’s death in 1940. The Untermyers had been major art collectors and had supported the work of a large variety of artists. (Overlook photo: Jonathan Wallen, courtesy of the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy)

At this point in our tour we headed into the great unknown into parts of the property where the gardens were less defined and the undergrowth had pretty much taken over.

We seemed to walk for ages through the woods (and were happy to be tracking sideways to the hill and not back up The Vista Steps) until we came to an extraordinary rustic structure quaintly named the Temple of Love. Constructed like a grotto of rocks it inspired me to go running to the top to look down on our group and another breathtaking view.

We seemed to walk for ages through the woods (and were happy to be tracking sideways to the hill and not back up The Vista Steps) until we came to an extraordinary rustic structure quaintly named the Temple of Love. Constructed like a grotto of rocks it inspired me to go running to the top to look down on our group and another breathtaking view.

There is certainly work to be done to shore up this free-form monument, but it’s impressive as is. Timothy recounted days of clearing brush from around it. It had been blighted not just by weeds but also by heaps of broken bottles and refuse accumulated through decades of neglect. (Temple of Love photo: Jonathan Wallen, courtesy of the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy)

We continued on through the woods passing rocky outcroppings that must have had meaning once and perhaps will again as the restoration by the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy continues.

Happily we skirted most of the direct hillside to get back to the top but were loath to exit the woods into the broiling sun. The cool walk through gardens had been a real eye opener. Originally a bucolic refuge from the city this amazing property is now an oasis tucked into a hectic suburb. Without doubt, with restoration, it will become a major destination for gardeners and non-gardeners alike. We thanked Timothy and got in our car trying to absorb the enormity of what we’d just seen.

Samuel Untermyer

Samuel Untermyer

By Katy Keiffer

The once magnificent Untermyer Gardens were a splendid gift to the City of Yonkers from lawyer, businessman and philanthropist, Samuel Untermyer (1858-1940). Untermyer bought the estate of Greystone and the adjoining properties for $171,500 in 1899, and spent the next four decades building the gardens for prosperity. He was, after all, an avid and knowledgeable gardener. Untermyer left 17 acres of his beloved gardens to the city of Yonkers; another approximate 26 acres were acquired in the 1990s.

Samuel Untermyer was born in Lynchburg, Virginia in 1858. Upon the early death of his father, Untermyer and his family moved to New York City where his mother opened a boarding house. At age 15 he obtained a job in a law firm. He went on to graduate from Columbia Law School.

A progressive, Untermyer was a tireless advocate for regulating the stock market and wrote many articles about the need for strict rules to govern Wall Street. He served as an advisor to the U.S. Treasury and was instrumental in creating the Federal Reserve Bank, as well as helping to write tax law governing excess profit, and income tax. He had the ear of many politicians, served as a confidant to Woodrow Wilson, and was a delegate to six Democratic national conventions.

Untermyer married Minnie Carl with whom he had three children. The two became linchpins of the New York cultural landscape providing funds for the New York Philharmonic and bringing Gustav Mahler to the United States, among other cultural endeavors. The Untermyers were serious art collectors, buying paintings, sculpture, Greek and Roman antiquities, furniture and tapestries for their residences in Yonkers and Manhattan. The collections were sold at auction in 1940.

Untermyer should be remembered as one of the first to identify the global threat that Hitler posed as Chancellor of Germany. On August 6, 1933, after returning from a European vacation, he made an address on WABC radio that was reprinted in the next day’s New York Times, in which he called upon all Americans to boycott any and all German merchants, goods, and transportation. His impassioned plea concludes, “with your support and that of our millions of non-Jewish friends, we will drive the last nail in the coffin of bigotry and fanaticism that has dared raise its ugly head to slander, belie and disgrace twentieth century civilization.” The boycott was ultimately unsuccessful, but the Untermyers remained very active in progressive politics throughout their lives.

New Yorkers owe a debt to Samuel Untermyer not just for his gift of gardens but for his tireless work as a civic leader. (Photo: United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Divison, Wikimedia Commons)

Lost and Found: Ornament at the Untermyer Gardens

By Eva Schwartz

One of the saddest truths in our field is that many of the garden ornament collections of great estates have been destroyed, lost, or sold off to anonymous buyers. Such is the case with Samuel Untermyer’s Greystone (the property’s original name), which once had more than eighty ornaments, including statues, fountains, and sundials. When Untermyer died in 1940, his gardens were bequeathed to the City of Yonkers–without an accompanying endowment. Consequently, the extraordinary landscape that Untermyer had honed over 40 years fell into ruin. A great many objects from the property were auctioned off and others became dilapidated or were vandalized. Luckily, the few artworks that remain on the property are truly extraordinary. And the silver lining, despite all the loss, is that there are still plenty of discoveries to be had. (Photo: United States Library of Congress National Digital Library, American Memory Collections, Wikimedia Commons)

One of the saddest truths in our field is that many of the garden ornament collections of great estates have been destroyed, lost, or sold off to anonymous buyers. Such is the case with Samuel Untermyer’s Greystone (the property’s original name), which once had more than eighty ornaments, including statues, fountains, and sundials. When Untermyer died in 1940, his gardens were bequeathed to the City of Yonkers–without an accompanying endowment. Consequently, the extraordinary landscape that Untermyer had honed over 40 years fell into ruin. A great many objects from the property were auctioned off and others became dilapidated or were vandalized. Luckily, the few artworks that remain on the property are truly extraordinary. And the silver lining, despite all the loss, is that there are still plenty of discoveries to be had. (Photo: United States Library of Congress National Digital Library, American Memory Collections, Wikimedia Commons)

The May 18, 1940 edition of The New Yorker included a feature article on Samuel Untermyer’s Greystone–an intimate portrait of the man and the behind-the-scenes workings of his estate, published just two months after his death–that chronicled not just the horticultural marvels of the gardens but also the abundance of ornament. Untermyer’s trusted horticulturist and estate manager, George Chisholm, gave Geoffrey Hellman, the reporter for the article, a tour of the property and remarked on a number of statues that were to be sold at auction. Among the many items that were at Greystone then but sold/lost were: a marble Venus Italica after an 1812 model by Antonio Canova, a group of Four Seasons, a figural fountain by Isidore Konti titled The Brook, and several rare Greek and Roman marbles, including a sculpture of Aphrodite and a torso of a youth after the model by Praxiteles. The Greek and Roman works were highlighted in the New York Times coverage of the Untermyer Sale, a spectacular event administered by the Parke-Bernet auction gallery and held over several days from May 10th to May 18th, 1940. Today we would love to know who bought these treasures, but alas, the auction records do not betray their clients’ anonymity. We do know that many of the lesser-quality garden pieces were sold for relatively little money, with composition urns going for about $5 each and a fountain with a bronze figure of Neptune selling for $400. (See the Parke-Bernet Galleries auction catalogs with lists of prices realized: The Untermyer Collection at Greystone, Yonkers, NY Part II, Public Sale May 15, 16 and 17, 1940 and Orchids and Other Rare Plants, Property of the Estate of the Late Samuel Untermyer Public Sale at Greystone, Saturday, May 18, 1940.)

Happily, a few important ornaments were donated to institutions where they are today given public prominence. Paul Manship’s celebrated bronzes of Diana and Actaeon (completed 1925) were given in 1948 by the City of Yonkers to the Hudson River Museum. At Greystone, Diana and Actaeon had adorned pedestals adjacent to the amphitheater in the Walled Garden. In October 1939, Actaeon, valued at the time at about $8,500, was stolen from the premises and sold to a junk shop for a mere $7.50. The junk shop owner learned that the figure was procured dishonestly, so hastily gave it back to the thief, who in turn then cut it up into four pieces and buried it! Needless to say, Untermyer must have been incredibly relieved when it was soon recovered by the police. (Photos: Courtesy of the Hudson River Museum, Gift of the City of Yonkers, 48.17.1 & 48.17.2)

Happily, a few important ornaments were donated to institutions where they are today given public prominence. Paul Manship’s celebrated bronzes of Diana and Actaeon (completed 1925) were given in 1948 by the City of Yonkers to the Hudson River Museum. At Greystone, Diana and Actaeon had adorned pedestals adjacent to the amphitheater in the Walled Garden. In October 1939, Actaeon, valued at the time at about $8,500, was stolen from the premises and sold to a junk shop for a mere $7.50. The junk shop owner learned that the figure was procured dishonestly, so hastily gave it back to the thief, who in turn then cut it up into four pieces and buried it! Needless to say, Untermyer must have been incredibly relieved when it was soon recovered by the police. (Photos: Courtesy of the Hudson River Museum, Gift of the City of Yonkers, 48.17.1 & 48.17.2)

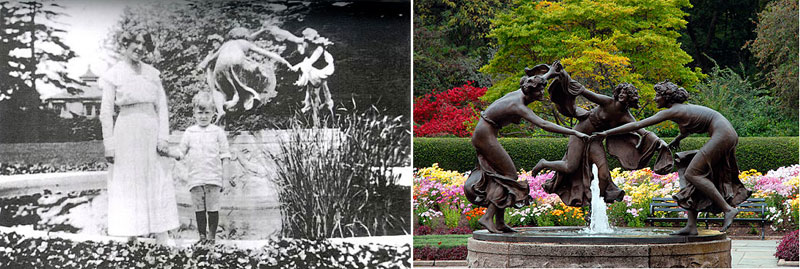

Another Untermyer treasure, the Three Dancing Maidens fountain (ca. 1910) by Walter Schott (1861-1938), now resides in the Conservancy Garden in Central Park, thanks to a gift by Untermyer’s sons. This figural fountain was once located at the front entrance of the Greystone mansion (above, left), in the center of the carriage circle. (Photos: Left, Untermyer Gardens Conservancy website; right, Central Park Conservancy website)

Untermyer’s love of beautiful objects and his assiduous devotion to art collecting was shared by his beloved wife, Minnie. They collected as a team and many of the lavish garden spaces were specifically built to accommodate the concerts, dance performances, and parties that Minnie hosted.

Untermyer’s love of beautiful objects and his assiduous devotion to art collecting was shared by his beloved wife, Minnie. They collected as a team and many of the lavish garden spaces were specifically built to accommodate the concerts, dance performances, and parties that Minnie hosted.

(Right: Isadora Duncan Dancing in Untermyer Park, ca. 1921-23, courtesy of the Hudson River Museum, Gift of Mrs. Serafian, 75.0.1548)

As great art patrons, the Untermyers commissioned works from the best sculptors of the day, including Ulric Henry Ellerhusen and Frederick G.R. Roth, in addition to Isidore Konti and Paul Manship.

Isidore Konti (1862-1938) was born in Austria, but came to the United States in his early thirties and from about 1893 until the turn of the century worked in Karl Bitter’s studio (having likely met Bitter while they were both working in Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exposition). Konti would become an important figure in the Yonkers art community, achieving prominence primarily through architectural and memorial commissions, including works for the Pan-American Building in Washington, DC, friezes for the renowned Gainsborough Studio Building in New York City, statues of Justinian and Alfred the Great at the county courthouse in Cleveland, and memorial fountains in New Orleans. In addition to contributing works for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, Konti also executed important sculptures for the World’s Fairs in Buffalo (1900), St. Louis (1904) and San Francisco (1915). Depicted above is the Main Building of the U.S. Government Group from the Buffalo Fair; Konti’s monumental sculpture, The Despotic Age is at the far right. (Photo: C. D. Arnold, Official Views of Pan-American Exposition, scanned by Dave Pape, Wikimedia Commons)

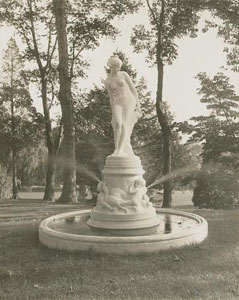

In 1906, the Untermyers commissioned Konti to sculpt The Brook, a marble fountain figure on a pedestal with putti and swans (right, shown at Greystone). The model had first been executed in plaster for the 1902 National Sculpture Society Exhibition held at Madison Square Garden, where it was widely admired, not the least of which by Untermyer. Not long after the commission was completed, Konti moved with his family from Manhattan to Yonkers, having been inspired by Greystone’s magnificent landscape.

In 1906, the Untermyers commissioned Konti to sculpt The Brook, a marble fountain figure on a pedestal with putti and swans (right, shown at Greystone). The model had first been executed in plaster for the 1902 National Sculpture Society Exhibition held at Madison Square Garden, where it was widely admired, not the least of which by Untermyer. Not long after the commission was completed, Konti moved with his family from Manhattan to Yonkers, having been inspired by Greystone’s magnificent landscape.

(Photo: A.B. Bogart, reproduced in The Sculpture of Isidore Konti, 1862-1938, exhibition catalogue, Hudson River Museum, 1975)

Isidore Konti also happened to be Paul Manship’s mentor at the time that Konti produced The Brook for Greystone. Manship (1885-1966), then a burgeoning artist, worked in Konti’s studio for a couple of years during which the two formed a lasting friendship. It is unclear whether Konti had anything to do with Manship’s later much-celebrated commissions for Greystone, though if nothing else, Konti’s 1906 fountain would have made Manship aware of Greystone and Untermyer. In 1909 Manship won the coveted Prix de Rome and spent the next three years there. Upon Manship’s return to New York, he established a friendship with William Welles Bosworth (1869-1966), Untermyer’s landscape architect. Their friendship, along with the Konti connection (presumedly), led to Manship’s first commission at Greystone in 1917.

Manship’s winged sphinxes (near right), commissioned in 1917, dominate Untermyer’s Walled Garden. The plans for this garden began taking shape in 1912, when Bosworth was hired to bring Untermyer’s vision to fruition. Perched on Ionic columns of Swiss Cippolino marble at the edge of the amphitheater, the sphinxes are representative of both the artist’s and architect’s devotion to historical precedent. Manship, often heralded for being a Modernist, drew inspiration from the severely pared-down, schematic forms of Assyrian and archaic Greek sculpture (far right), a predilection evidenced by the sphinxes at Greystone. (Serendipitously, Manship’s “archaic” approach worked extremely well with the stylized architecture and interiors of Art Deco–making him one of the most successful sculptors of the period.) The sphinxes are also in perfect keeping with Bosworth’s design that incorporated disparate Indo-Persian, or Mughal, influences along with those of ancient Greece. This garden is an amalgam of historical styles unified by crenellated walls, connecting balustrades, a cohesive mosaic scheme and repeated architectural forms. (Manship sphinx photo: Jonathan Wallen, courtesy of the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy; Archaic sphinx-shaped finial in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Rosemaniakos from Beijing, Wikimedia Commons)

Manship’s winged sphinxes (near right), commissioned in 1917, dominate Untermyer’s Walled Garden. The plans for this garden began taking shape in 1912, when Bosworth was hired to bring Untermyer’s vision to fruition. Perched on Ionic columns of Swiss Cippolino marble at the edge of the amphitheater, the sphinxes are representative of both the artist’s and architect’s devotion to historical precedent. Manship, often heralded for being a Modernist, drew inspiration from the severely pared-down, schematic forms of Assyrian and archaic Greek sculpture (far right), a predilection evidenced by the sphinxes at Greystone. (Serendipitously, Manship’s “archaic” approach worked extremely well with the stylized architecture and interiors of Art Deco–making him one of the most successful sculptors of the period.) The sphinxes are also in perfect keeping with Bosworth’s design that incorporated disparate Indo-Persian, or Mughal, influences along with those of ancient Greece. This garden is an amalgam of historical styles unified by crenellated walls, connecting balustrades, a cohesive mosaic scheme and repeated architectural forms. (Manship sphinx photo: Jonathan Wallen, courtesy of the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy; Archaic sphinx-shaped finial in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Rosemaniakos from Beijing, Wikimedia Commons)

The skilled sculptor, Ulric Henry Ellerhusen (1879-1957), also left his mark on the Walled Garden. Luckily, his work was of the permanent architectural sort, and installed some distance above the ground–so it was never at risk of being sold or lost! Ellerhusen was responsible for the carved stone plaque above the main gateway into the garden. This piece, depicting Artemis in a recumbent pose, is a fitting choice for a garden that owes its forms to ancient art. Ellerhusen may have come to the Untermyer project through Isidore Konti, since they both had worked at various times in the studio of Karl Bitter. Bitter had been an influential sculptor at several World’s Fairs, and was the head of sculpture programs for the 1904 St. Louis Fair and the 1915 San Francisco Fair. Both Ellerhusen and Konti worked directly under Bitter during those expositions, so it would be fair to assume that they were associates. Having received one of the earliest commissions at Greystone, Konti may have opened the door for other sculptors in subsequent years. Furthermore, as luck would have it, William Welles Bosworth was also very much involved with the World’s Fairs, having been head architect John Carrère’s right-hand man for the 1900 Buffalo exposition. It really was a very small community.

With regard to Ellerhusen’s plaque above the doorway, one wonders if the selection of Artemis was meant to relate to the fantastic floor mosaic of Medusa, positioned in the center of the garden’s Greek rotunda. At the 6th-century BC Temple of Artemis in Corfu, Greece, the Gorgon Medusa is depicted on the pediment rather than Artemis herself. When German archaeologist Wilhelm Doerpfeld (1853-1940) unearthed the pediment in 1911, it made international news (the pediment was described in detail in the New York Times on June 18, 1911). In the 1911 article, The Temple was ascribed to Apollo, but by 1915 sources like The American Year Book: A Record of Events and Progress, edited by Francis Wickware, were calling it the Temple of Artemis. It has been theorized that Medusa represented the darker side of Artemis–that they were a conflation of sorts, united by their devotion to wild beasts of all kinds. Although unclear whether Bosworth, Ellerhusen, or Untermyer would have made these connections, it is certainly a question ripe for further inquiry. The Untermyer Gardens Conservancy has made the astute judgment that the Medusa mosaic represents the symbolic joining of two bodies of water–the Hudson River and the ornamental fountain pools of the Walled Garden. This would make sense considering that Medusa is the offspring of two primordial sea gods. But perhaps there might also be a link to the Artemis plaque?

With regard to Ellerhusen’s plaque above the doorway, one wonders if the selection of Artemis was meant to relate to the fantastic floor mosaic of Medusa, positioned in the center of the garden’s Greek rotunda. At the 6th-century BC Temple of Artemis in Corfu, Greece, the Gorgon Medusa is depicted on the pediment rather than Artemis herself. When German archaeologist Wilhelm Doerpfeld (1853-1940) unearthed the pediment in 1911, it made international news (the pediment was described in detail in the New York Times on June 18, 1911). In the 1911 article, The Temple was ascribed to Apollo, but by 1915 sources like The American Year Book: A Record of Events and Progress, edited by Francis Wickware, were calling it the Temple of Artemis. It has been theorized that Medusa represented the darker side of Artemis–that they were a conflation of sorts, united by their devotion to wild beasts of all kinds. Although unclear whether Bosworth, Ellerhusen, or Untermyer would have made these connections, it is certainly a question ripe for further inquiry. The Untermyer Gardens Conservancy has made the astute judgment that the Medusa mosaic represents the symbolic joining of two bodies of water–the Hudson River and the ornamental fountain pools of the Walled Garden. This would make sense considering that Medusa is the offspring of two primordial sea gods. But perhaps there might also be a link to the Artemis plaque?

Frederick George Richard Roth (1872-1944) carved the lion mask fountains situated on the walls of the rotunda pool. Roth was one of the most revered animaliers of the day, who served years later as the head sculptor for the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. (To see some of the masterworks he sculpted for Central Park, including the beloved statue of the heroic dog, Balto, see “Sculpture Walk in Central Park” in our Central Park issue of Focal Points.) Roth was also a prominent figure on the World’s Fair sculpture scene. Perhaps this connection led to his being chosen to produce the fountain masks. (Photo:

Frederick George Richard Roth (1872-1944) carved the lion mask fountains situated on the walls of the rotunda pool. Roth was one of the most revered animaliers of the day, who served years later as the head sculptor for the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. (To see some of the masterworks he sculpted for Central Park, including the beloved statue of the heroic dog, Balto, see “Sculpture Walk in Central Park” in our Central Park issue of Focal Points.) Roth was also a prominent figure on the World’s Fair sculpture scene. Perhaps this connection led to his being chosen to produce the fountain masks. (Photo:

American Homes of To-Day, 1924)

One of the most outstanding features of the Untermyer property–beyond The Walled Garden–is the circular overlook at the base of The Vista Steps. Dominating the space are two monolithic columns dating to the Roman period. Legend has it that the illustrious architect Stanford White (1853-1906) imported these columns from Italy–and it’s not at all a stretch to assume that he did. White had a talent for buying grand ornaments, both ancient and made-to-order, often conducting whirlwind European buying trips. He literally had warehouses full of antiques (and pieces made to look like antiques) ready to be installed at clients’ estates (use the link to our “Marble in America” issue of Focal Points provided in Barbara’s introduction).

Stanford White died several years before the columns were installed at Greystone, so it is clear that they were not imported for Untemyer (unless they were purchased and stored long before the gardens were built?). Still, it is fair to conclude that they were part of White’s collection. The contemporary writer, Augusta Owen Patterson, author of the influential American Homes of To-Day (1924), noted in that publication that White had purchased the columns. Patterson was employed for years by Town and Country magazine as an arts writer and editor, covering the luxurious properties of the day. Patterson proved in her books and articles that she was a knowledgeable and discerning art critic. Thus Patterson’s linking of White to the columns was probably reasonably substantiated. There may never be hard evidence, of course, but that would be normal considering the boatloads of objects that White imported with only the scantest documentation.

The heavily vandalized sculptures of a lion and a horse, situated at Greystone’s riverside gatehouse, are also the subjects of speculation– and there’s even less to go on than the Stanford White columns. The now-headless horse and lion have been linked to Edward Clark Potter, the sculptor responsible for the famous lions outside the main branch of the New York Public Library (1911), though this attribution is not at all documented. Certainly Potter was working within a small circle of accomplished sculptors, which would have made Bosworth aware of him. Potter was an active member of the National Sculpture Society, as were all the sculptors who contributed to the Untermyer gardens. (Incidentally, Stanford White had been a founding member of this important society that sought to increase the public’s appreciation for sculpture.) Potter had also been one of the sculptors intimately involved with the decorations at the many World’s Fairs, so there is every reason to believe that he could have come to the commission through that circle of friends. Or, since the lions had been installed with such fanfare at the New York Public Library in 1911, there is reason to think that Untermyer himself might have sought Potter out. The Untermyer lion is not particularly similar to the Library lions, so it would be a leap to make the attribution on stylistic grounds, but anything is possible!

The heavily vandalized sculptures of a lion and a horse, situated at Greystone’s riverside gatehouse, are also the subjects of speculation– and there’s even less to go on than the Stanford White columns. The now-headless horse and lion have been linked to Edward Clark Potter, the sculptor responsible for the famous lions outside the main branch of the New York Public Library (1911), though this attribution is not at all documented. Certainly Potter was working within a small circle of accomplished sculptors, which would have made Bosworth aware of him. Potter was an active member of the National Sculpture Society, as were all the sculptors who contributed to the Untermyer gardens. (Incidentally, Stanford White had been a founding member of this important society that sought to increase the public’s appreciation for sculpture.) Potter had also been one of the sculptors intimately involved with the decorations at the many World’s Fairs, so there is every reason to believe that he could have come to the commission through that circle of friends. Or, since the lions had been installed with such fanfare at the New York Public Library in 1911, there is reason to think that Untermyer himself might have sought Potter out. The Untermyer lion is not particularly similar to the Library lions, so it would be a leap to make the attribution on stylistic grounds, but anything is possible!

There is another ornament of note that survives on the Untermyer property–a Rosso Verona marble wellhead. Though seemingly haphazardly placed and surrounded by overgrowth, it is nonetheless a significant specimen. This piece is typical of the wellheads made in Italy at the turn of the twentieth century for the export market. Crafted in the spirit of Medieval and Renaissance wellheads, objects such as this were regularly acquired by Gilded Age estate owners who desired Old World sophistication. It is even possible that Stanford White imported this wellhead, since he was buying and distributing so many pieces of this sort. It would be fun to find a glorious new location for it on the grounds of the Untermyer Gardens, now that the restoration is in full swing. The heartening fact despite all the beautiful ornaments lost over the years is surely this: the ones that are left are undeniably worth visiting, studying and, ultimately, saving.

There is another ornament of note that survives on the Untermyer property–a Rosso Verona marble wellhead. Though seemingly haphazardly placed and surrounded by overgrowth, it is nonetheless a significant specimen. This piece is typical of the wellheads made in Italy at the turn of the twentieth century for the export market. Crafted in the spirit of Medieval and Renaissance wellheads, objects such as this were regularly acquired by Gilded Age estate owners who desired Old World sophistication. It is even possible that Stanford White imported this wellhead, since he was buying and distributing so many pieces of this sort. It would be fun to find a glorious new location for it on the grounds of the Untermyer Gardens, now that the restoration is in full swing. The heartening fact despite all the beautiful ornaments lost over the years is surely this: the ones that are left are undeniably worth visiting, studying and, ultimately, saving.

A Conversation with Timothy Tilghman

A Conversation with Timothy Tilghman

By Katy Keiffer

On a blistering July day the BIGA team motored up to Yonkers for a tour of the Untermyer Gardens, led by head gardener and horticulturalist Timothy Tilghman. His enthusiasm for the gardens and his work was evident from the onset of our tour.

Tilghman started his career by studying plant sciences at the University of Missouri. But once he took an internship at the Powell Gardens in Kansas City, he switched his focus to ornamental horticulture, a decision enabling him to design gardens, work outdoors instead of in a lab, and connect with the public. “I chose this career as something I could never exhaust or get bored with. Working in public horticulture is a lot about the art as well as the science of gardening.” Subsequent stints at Willowwood Arboretum in Chester Township, NJ, Rocky Hills in Chappaqua, NY, and Wave Hill in the Bronx have only served to cement his interest in public gardens.

As he steered us around the remarkable Walled Garden, he explained some of the significant challenges inherent to landmarked projects. In the case of the Untermyer Gardens the state landmarks commission has designated 1924 as their target year, and the task of the horticulturist is to represent that era faithfully despite far more limited funds and manpower. To put that challenge into perspective, it should be noted that Samuel Untermyer employed 60 full-time gardeners and had 60 greenhouses to grow plants that were rotated according to the season. Today, Tilghman is the only full-time gardener. Thus finding ways to honor the original intent and design requires a combination of hard work and ingenuity in planting. “We are trying to get the same idea as Bosworth (the property’s designer) had, while finding a solution that is less labor intensive. Meanwhile, being a public garden we do want to have an educational mission here to show different plants; what can be in bloom in the season and how to use the plants.”

Tilghman has been at the Untermyer Gardens for only a year, but he has accomplished prodigious feats of clearing the land, and in the process has discovered long-lost features that were literally buried in brush and trash. When we commented on all the hidden gems he grinned, saying ” I love being here…as a gardener and as a boy digging for treasure….”

One of those discovered features is the Temple of Love, a man-made grotto complete with weep holes for tiny cascades and plantings, a small pool and a diminutive stream. “It took the city’s largest dump truck and an entire troop of boy scouts to clear out the bottles and cans that filled the area below the Temple.”

As the work of restoration is accomplished, it is Tilghman’s ambition to provide much more in the way of public education. “It’s not a mandate from the state, just my own personal goal. …I also want to see the gardens function as a contemporary resource for horticulturists and amateur gardeners.” To this end, he hopes to organize a volunteer program where gardeners can come in and work with him offering an opportunity for the exchange of information and skills. He has plans to label all the plants so visitors can identify what they are looking at, and see how to use them in their own gardens. He wants to continue with the tours highlighting the history of the gardens but also branch out to include subjects such as the principles of garden design and horticulture. “We aren’t there yet, but we hope to be instituting those features in the future.”

In the end, what drives Tilghman and his work in public gardens is this: “Everything you do is for a bigger purpose than just your own manipulation of plants.”

The Untermyer Gardens are located at 945 North Broadway in Yonkers. The Walled Garden is open year round from Monday through Saturday, 7am – sunset, and on Sundays, from April till October, from 12pm – dusk. To learn more about the Gardens, get directions, and view scheduled tour dates (beginning in the Spring) visit the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy website.

We are exhibiting at the Winter Antiques Show at the Park Avenue Armory (67th and Park Avenue) through February 3rd. We encourage you to visit the show if you are in the area.

We are looking forward to working on our next Focal Points that will feature the first public parks…cemeteries. We’ve gathered images from several noteworthy cemeteries including Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, Greenmount Cemetery in Baltimore, New Orleans’ St. Louis Cemetery #1, Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, and, if we can reach far back in our pre-digital archives, Forest Lawn in Glendale, CA.