The Cyclades, Part II: From Schinoussa to Athens (with a stop in Atlantis?)

By Barbara Israel

As you may remember, Part I of my Greek travelogue ended with our visit to Delos. We next anchored off the incongruously (to my way of thinking) named Paros and Anti-Paros. One of the obvious pleasures of visiting the Cyclades are the many seafood restaurants, readily identifiable as “YAPOTABEPNA”, and we had lunch two days in a row in such ‘tavernas’.

I wasn’t entirely thrilled with the line of octopus hanging outside the restaurant but it made an interesting photo. The first lunch, on Anti-Paros, was a bit predictable and the Greek salad reminded me of a New York diner! But the next day in Schinoussa I could tell right away that that particular taverna had impeccable taste and it wasn’t just the food.

The restaurant pulled out all the stops and served us their own homegrown vegetables, a multitude of incredible fish and beer by the gallon. The only clues we had of Greece’s economic problems on the whole trip was 1) the cost of that meal and 2) that we had to pay in cash!

Once again swimming off the island was amazing in and under the overhanging cliffs that revealed layers of ash from thousands of years of volcanic activity.

After leaving these quiet little islands we moved on to Santorini (classically known as “Thera”) where an entirely different experience awaited us. In terms of volcanic activity Santorini leads the list. Sometime between 1627-1550 BC (the exact date is disputed) their volcano erupted. Some consider it the single largest eruption in the history of the world. It is known as the “Theran” eruption, or alternately, the “Minoan” eruption as it is believed to have entirely wiped out the very advanced Minoan civilization in this part of the Aegean.

Most of this history was unknown to me at the time but soon became almost commonplace when three of us left the boat to visit the excavation site at Akrotiri on Santorini. In 1967, the Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos (1901-1974) started excavating this Bronze Age settlement that dated to the 5th millennium BC. The site had been preserved, like Pompeii, by volcanic ash from the gargantuan eruption of Santorini.

Most of this history was unknown to me at the time but soon became almost commonplace when three of us left the boat to visit the excavation site at Akrotiri on Santorini. In 1967, the Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos (1901-1974) started excavating this Bronze Age settlement that dated to the 5th millennium BC. The site had been preserved, like Pompeii, by volcanic ash from the gargantuan eruption of Santorini.

I was surprised to find the whole protected by an enormous framed roof. We soon realized that this had been a highly developed and cultured civilization with a very refined appreciation of art, fully expressed in their frescoes.

One of the fascinating facts about this site is that scientists have concluded, because no valuables or bodies were found in the ash, that the residents seemed to have had adequate warning of the impending eruption and had time to collect their belongings and safely evacuate the area.

Some of the structures were surprisingly advanced and could be seen to have been two- or three-story buildings. In one room storage jars, or “pithoi”, were arranged in such a way that Marinatos had concluded that they must have held provisions for workers, presumably weavers as they had found loom-weights nearby. I was particularly taken with the painted jar and wished we could copy its exquisite form!

In places where wooden objects had rotted away the excavators were able to pour plaster into the negative spaces between the ashes to produce fairly exact replicas of the original pieces. We were told the castings in this photo were replicas of beds.

In places where wooden objects had rotted away the excavators were able to pour plaster into the negative spaces between the ashes to produce fairly exact replicas of the original pieces. We were told the castings in this photo were replicas of beds.

From the quiet spaces of Akrotiri we took a taxi up the very steep hill (we could have taken a donkey or the funicular) to “Fira” the capital of Santorini where tourists were plentiful. So much of the history of this island revolves around the volcano and its past activities. The huge harbor is called the “Caldera” as it is the crater of the enormous volcano that, after the explosion, had collapsed and filled with seawater. The views from the top are spectacular but I wouldn’t call the island exactly undiscovered.

Courtesy www.visibleearth.nasa.gov

One of the strangest theories about Santorini is that it was the Theran eruption that buried the legendary city of Atlantis. The History Channel recently aired a special, “Atlantis Found“, that explores this theory and draws certain conclusions from the circular topography of Santorini and other physical aspects of the area. They took the details of Plato’s description of Atlantis (suspected by some scholars to be a pure fabrication by Plato to prove that powerful, greedy leaders come to bad ends) and using all sorts of underwater soundings as well as a multitude of other evidence came very close to authenticating the theory. It’s worth watching if you’re as curious as I was.

They used Akrotiri’s excavations as a starting point and even show as proof one of the wall paintings/frescoes that I was lucky enough to see at the Sant Museum, a private museum, at the very top of Fira. While at the museum we heard that professors at Princeton had been responsible for the excellent restorations of this fisherman and the other ancient paintings.

The painting below is thought to represent the last and final voyage of the Theran fleet before the eruption and resulting destruction of the Minoan civilization. The left side of the painting illustrates a circular city that the History Channel expert concluded was a representation of Atlantis. Keep in mind that claims of locating Atlantis have been circulating for thousands of years and perhaps this is just one more…or, perhaps, it’s the real thing!

The painting below is thought to represent the last and final voyage of the Theran fleet before the eruption and resulting destruction of the Minoan civilization. The left side of the painting illustrates a circular city that the History Channel expert concluded was a representation of Atlantis. Keep in mind that claims of locating Atlantis have been circulating for thousands of years and perhaps this is just one more…or, perhaps, it’s the real thing!

Our next island was Milos, known for obsidian mining, sulfur baths and the extraordinary discovery of the Venus de Milo. As our car pulled along the road, right at the point in the photo below, the driver told us that this was the very spot a farmer in his field discovered her. Needless to say I was amazed at what was now an entirely rural almost desolate setting.

The story on the signpost read as follows: On April 8th in 1820 George Kentrotas was working in his field when he unearthed a small cave in which he found half of the Venus statue. A French officer who happened to be nearby convinced Mr. Kentrotas to search for the other half and indeed he found it. After realizing its extraordinary artistic value, and along with some fast maneuvering, the French consul succeeded in purchasing it for the French king, Louis XVIII. A seriously abridged version of how she ended up in the Louvre!

ust below that hallowed field was a Roman amphitheater still in the stages of reclamation and development. The guide told us that this one was considered “late” as it was Roman. Some of the fragments, such as those on the right in this photo, that hadn’t yet been incorporated were beautiful on their own. In another part of Milos we found sulfur baths settled in the rocky coastline.

On our way to Athens we stopped briefly in Poros to check out the shops and buy last minute presents to take home (alas, not at the above emporium!). It was quite a jarring change from the quiet, serene islands—it appeared that tourism remains a strong impetus to the Greek economy.

On our way to Athens we stopped briefly in Poros to check out the shops and buy last minute presents to take home (alas, not at the above emporium!). It was quite a jarring change from the quiet, serene islands—it appeared that tourism remains a strong impetus to the Greek economy.

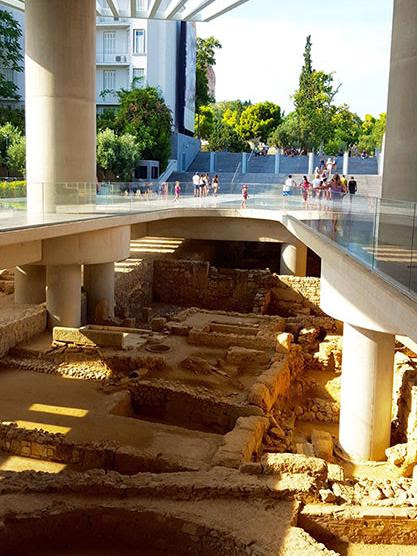

Our next and last stop was Athens. We docked at Piraeus and made our way into the city to see (gasp, so excited) the Acropolis. Before we made the big climb to the top we stopped at the new Acropolis Museum. By the 1970s the original museum on the Acropolis was deemed too small to display all the artifacts discovered on site so now, after many years of planning and construction, Athens finally has a world-class institution to display its inimitable collection of antiquities.

It is absolutely spectacular. Designed by Bernard Tschumi Architects with Michael Photiadis it was completed in 2007. By using laminated glass plates on the floor they revealed an ongoing excavation beneath. I’m sure many of you have been there already but if given to dizziness it is not advisable to look down!

The entire museum uses natural light to show the statues, friezes and fragments so all day the illumination changes as it would if you were actually outdoors. On most of the floors the guards were very strict…NO PICTURES ALLOWED. I don’t understand why because there were other floors that it was entirely permissible.

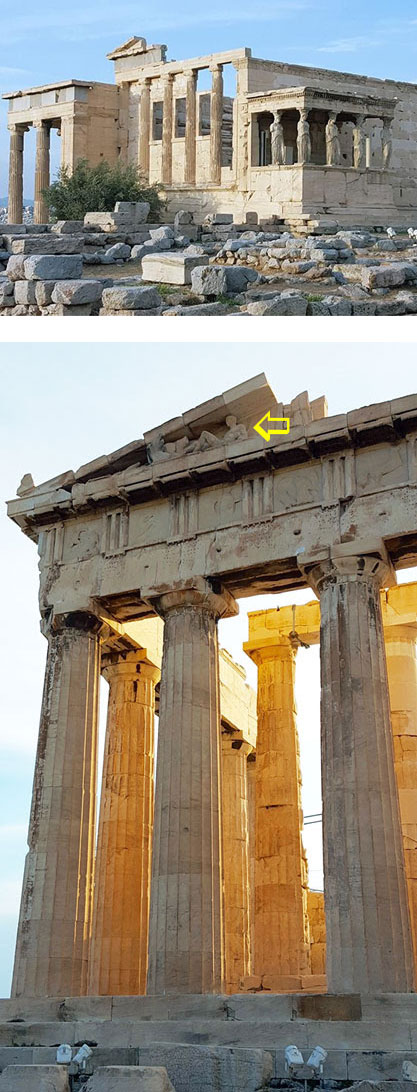

Admirers surrounded the caryatids from the Erechtheion but I waited them out and got a good picture. Originally there were six “Koroi” as they were called, but one is in the British Museum and the other five are here. Presently the six caryatids currently on the Erechtheion are cast copies of these. Note: It was Lord Elgin (famous for the marbles) himself who carried off the sixth caryatid.

Admirers surrounded the caryatids from the Erechtheion but I waited them out and got a good picture. Originally there were six “Koroi” as they were called, but one is in the British Museum and the other five are here. Presently the six caryatids currently on the Erechtheion are cast copies of these. Note: It was Lord Elgin (famous for the marbles) himself who carried off the sixth caryatid.

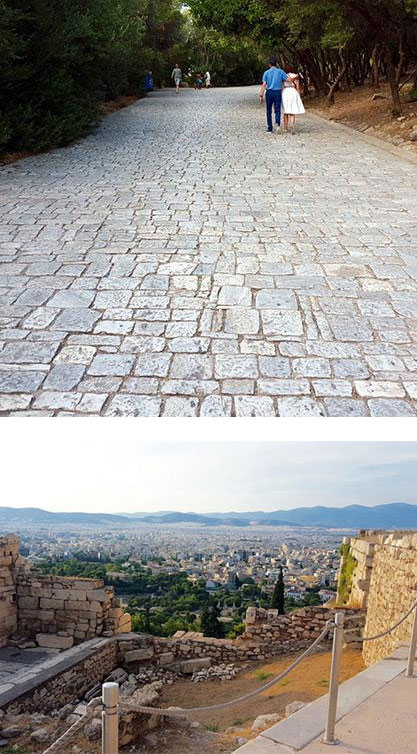

At last it was time to head to the Acropolis. We traipsed up the marble pathway that leads there.

Many of you have surely been there but I was struck by the vast acres of low buildings that comprise Athens. There are no tall buildings obscuring the 360 degree view.

As we climbed up I got more and more excited to see the Parthenon and was stunned when it finally came into view. Oh no, just like New York City, decked out in scaffolding!

We walked around and made our way over to the Erechtheion that looked in very good condition. It had been completed in 406 BC and was dedicated to Athena on the east side and to Poseidon and others on the west. The North Porch has powerful Ionic columns and the South Porch supports are the caryatids. The Athenians considered this a most sacred building.

We walked around and made our way over to the Erechtheion that looked in very good condition. It had been completed in 406 BC and was dedicated to Athena on the east side and to Poseidon and others on the west. The North Porch has powerful Ionic columns and the South Porch supports are the caryatids. The Athenians considered this a most sacred building.

While walking around the exposed sides of the Parthenon I managed to spot a lone reclining male figure in the east pediment, the whole of which originally depicted the birth of Venus. This is a replica as the Elgin marbles are comprised of a number of figures from the east pediment, among other locations, including this figure (Here’s a link to view the original in the British Museum). The figure is thought to be Dionysus.

As we walked down I wondered how long it would take to complete the restoration of the Parthenon but decided that the impression of standing on that huge plateau looking down upon an ancient city certainly compensated for seeing the Grand Lady in her curlers!

What an incredible trip this was! I hope you have or will have the opportunity to see some of these awe-inspiring sites of classic Greek history!

Augustus of Prima Porta and the Lessons of Restoration

By Eva Schwartz

Photo: Michal Ostend from Brussels, Belgium (uploaded by russavia) [CC-BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The Augustus of Prima Porta (right) is certainly one of the most celebrated examples of Imperial Roman sculpture, but it is also a reminder of the philosophical debate surrounding the restoration of Antique statuary. Housed in the Vatican Museum collection, it is thought to have been commissioned in 15 AD by Tiberius (42 BC-37 AD), as a memorial to his adoptive father, Emperor Augustus (63 BC-14 AD). It was discovered in 1863 in Prima Porta, just outside Rome, at the villa that had belonged to Augustus’ wife, Livia (58 BC-29 AD).

A few months ago, Barbara was delighted to purchase an early 20th-century carved marble replica of Augustus. The magnificent scale of this piece (at over 9 feet, it’s 2 feet taller than the original) makes it one of the most commanding she has ever owned. While unmarked, she attributes it to J. Chiurazzi & Fils, the Italian firm known for producing the highest quality Antique reproductions from the mid-19th century on. As Barbara had long admired the Chiurazzi-attributed Augustus at Ca d’Zan, the Ringling estate in Sarasota, FL, and had featured that piece in her book, Antique Garden Ornament: Two Centuries of American Taste, she was delighted to find another of equal stature.

When the original statue was discovered in 1863, it was remarkably intact, with only the accessories (e.g. scepter) lost and some fingers missing on both hands. Restoration of the fingers was overseen by the Carrara-born, Roman sculptor, Pietro Tenerani (1789-1869), who had been classically trained in Bertel Thorvaldsen’s studio in the early 1810s. Of most significance was the restoration of the figure’s right index finger. As noted by Georg Daltrop, the former Curator of Classical Antiquities at the Vatican, the position of the restored hand, and of the index finger in particular, calls to mind Augustus’ great oratory skills, with the emperor having been captured mid-address. This gesture carries meaning that affects our perception of this statue. However, Daltrop contends in a 1982 publication that the right hand could just as easily have been holding a lance, or even more likely, the valuable Eagle Standard of Rome (since the recapture of the lost Standard was one of Augustus’ great achievements, and the historical event is depicted on the statue’s armor). Had the hand been restored in this way, grasping such an object, it would suggest a heroic military victory, but not necessarily an oratory one. [See The Vatican Collections: The Papacy and the Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), 1982, p. 208.] Indeed, if the figure itself had been discovered twenty years later, it may not have been restored at all, the tide having turned at that point away from the restoration of Antique figures.

The immensity of Augustus!

Photo: Barbara Israel

A replica of the Eagle Standard of Rome.

Photo: No machine-readable author provided. Matthias Kabel assumed (based on copyright claims). [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The Bateman Mercury, an amalgamation of antique and restored elements.

(Marble, Roman, 2nd century copy after a Greek original of the 4th century BC)

William Randolph Hearst Collection (48.24.15), Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Lansdowne Athlete, an example of de-restoration, now without early restorations.

(Marble, Roman, 1st c. BC/1st c. AD copy after a Greek original of ca. 340-330 BC by Lysippos.)

William Randolph Hearst Collection (49.23.12), Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Lansdowne Herakles, an example of re-restoraion, with 18th-century restorations re-applied.

(Marble, Roman, ca. 125 AD), Gift of J. Paul Getty, Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum

During the Renaissance, when an enormous number of ancient sculptures were found, there was a general feeling that figures should not be left in fragmentary form, but, rather, made whole again. There was little to no emphasis on achieving historical accuracy, as most Renaissance sculptors saw the restoration of ancient fragments as an opportunity for creative invention. Sometimes, fragments from two different statues were brought together to create a new piece, as in the case of the Bateman Mercury at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where the head and torso are “married”. Michelangelo, who admired the unadulterated quality of fragments, protested against the restoration practices of his day.

[For an accounting of Michelangelo’s esteem for the Belvedere Torso, for example, please refer to Ulisse Aldrovandi, “Delle statue antiche…” in Lucio Mauro, Le Antichità della città di Roma, Venice, 1556, cited in Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique (New Haven, CT: Yale University), 1981, p. 312.]

As observed by Jerry Podany, an antiquities conservator at the J. Paul Getty Museum, “it is fair to say that we have only begun to understand the role that restorers have played over the centuries in both clarifying and distorting our knowledge and perception of antiquity” (from “Lessons of the Past”, a paper delivered at the symposium History of Restoration of Ancient Stone Sculptures held at the Getty on October 25-27, 2001). The approach to restoration taken during the Renaissance continued through the 17th century, with the idea being that a sculpture could not inspire or educate unless it was complete. Unfortunately this led at times to sculptors having little compunction about altering an ancient statue in order to make it fit their own artistic vision.

A reassessment of the purpose of restoration began in the 18th century, with an emphasis on historical accuracy coming more heavily into play. Critics railed against irresponsible and misguided restoration practices, leading to the development of new, more reversible conservation techniques. Indeed, restoration was emerging as more a scientific field than an inventive one. A century later, the philosophy had shifted fully towards de-restoration, even sparking the removal of previously restored elements.

Augustus of Prima Porta in our Katonah allée, before finger restoration

Augustus‘ finger, blocked out by our conservator.

Photo: Charles A. Johnson

What a conundrum, when you think about it! How can we understand these statues as they once were, in all their glory, if they aren’t restored? At the same time, in the act of restoring, how can we ever escape the prejudices, perceptions, and even the fashions of our own time? It is the latter question that led, in part, to the most current conservation philosophy, affectionately termed “re-restoration”. The recent (within the last couple of decades) view is that old restorations are, in themselves, historically significant. They say something important about the tastes and preferences of the time in which they were done. Consequently, some restored elements that were taken away early in the 20th century have been added back on.

All of our fussing over Augustus of Prima Porta‘s hands and fingers is therefore a meaningful exercise, as even the smallest reproductions play a role in our understanding of ancient works. The Ca d’Zan Augustus is missing fingers on both hands, but seems to have been carved this way to mimic the state of the statue when discovered in 1863. It’s hard to know for sure, as fingers are known to break fairly easily, but the breaks on the Ca d’Zan figure are neatly squared off and seem purposeful. By comparison, our Augustus arrived with a missing right index finger that was clearly the result of a break. When our conservator set about the task of restoration, he replicated the finger based on the additions done in the 1860s. There were two reasons for this: first, this is how it appears in the 1929 Chiurazzi catalog, and second, this is the way the world knows the statue. The question of whether Augustus‘ right hand once held the Eagle Standard of Rome isn’t inconsequential, but at this point it’s moot. Pietro Tenerani’s 1860s team forever affected the form and perception of this iconic statue. And all that is left for us to do is to honor his contribution to this historic and important work of art.

The Spirit of Arcadia

By Eva Schwartz

Augustus of Prima Porta in our Katonah allée, before finger restoration

Recently we acquired a pair of terra-cotta figures: a Marquis and Marquise, each seated on the back of a goat. Our figures are unmarked and undated, but are likely to have been made in the second half of the 19th century by one of two French terra-cotta companies: Gossin Freres, of Paris, or F. & A. Jacquier, of Caen. The ca. 1880 Marquis and Marquise appear in a Gossin Freres catalog of ca. 1856 and in an undated Jacquier catalog of about the same period, but the designs were likely produced for a number of decades. The pair of figures is almost impossibly charming–the appealing, youthful, figures in 18th-century dress, the goats enchanting and impeccably groomed! We were so taken with them that it was a minute or two before we questioned our decision-making skills: youths on goats? Had we gone mad?

Neda River waterfall in Peloponnese Courtesy Sp!ros/CC-BY-SA-3.0

But then we remembered Arcadia, and the importance of this theme in art and literature, and kids on goats didn’t seem so strange after all. In Greek mythology, Arcadia was a bucolic paradise where shepherds and shepherdesses, satyrs and nymphs were presided over by Pan, the benevolent god of nature, herds, and flocks. Historically located in the mountains of Peloponnese, Arcadia represented an idealized rustic retreat, a place to escape the demands of regular life. The Arcadian way of being indicated the perfect communion between man and nature.

Engraving by J.W. Cook, 1825, via Wikimedia Commons

Arcadia was the frequent subject of pastoral poetry and verse in ancient Greece and Rome. The first pastoral poet on record was Theocritus (ca. 310 BC – ca. 245 BC), whose works, particularly his “Idylls”, honored Arcadia as both a physical locale and an aspirational ideal. Arcadia signified the very essence of simplicity and grace. And, naturally, the splendors of the landscape elevated the human spirit. In Theocritus’ fifth Idyll, a goatherd and shepherd engage in a singing contest, prompting the shepherd to proclaim:

More sweetly will you sing, seated beneath this wild olive and this shady grove. Chill water trickles yonder; while here springs the grass, here is spread a leafy couch, and here the locusts chatter.

Nicolas Poussin, Landscape with Polyphemus, 1649,

The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera, 1717,

Musée du Louvre

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Shepherdess, 1750-52,

Milwaukee Art Museum, [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Theocritus’ Idylls were emulated not only by Roman poet, Virgil (70 BC – 19 BC), but also by Romantic-era wordsmiths, Lord Byron (1788-1824), John Keats (1795-1821), and William Wordsworth (1770-1850), among others. Literary scholar, Martha Hale Shackford, wrote in 1904 that the pastoral idyll is a “presentation of…the joyous life of herdsmen…The descriptions of nature, the stories of love, the delight in songs…are all part of a lyric mood…[that] catches at some eternal yearning in the heart of man”. (From “A Definition of the Pastoral Idyll”, in PMLA, the journal of the Modern Language Association, Vol. 19, No. 4, 1904.)

In 17th- and 18th-century France, some of the most fashionable art works were Arcadian in nature. These ideals were expressed by (among others) Baroque painter, Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), whose pastoral landscapes were populated by characters from classical mythology, and, later, by Rococo painters Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721) and Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806). [The Baroque period in European painting spanned the years 1600 to 1715, the Rococo period 1725-1775.] Watteau’s signature and much-copied paintings of “fêtes galantes” depicted elegantly-dressed aristocrats frolicking in romantic outdoor settings. Not surprisingly, sheep and goats were frequently included, all the better to embody the spirit of Arcadia!

Le Hameau, Versailles, Courtesy Azurfrog/CC-BY-SA-3.0

Marie-Antoinette (1755-1793) was one enthusiastic observer of Arcadian ideals. Between 1783 and 1787, she ordered the construction of a model farm, on the grounds of the Petit Trianon at Versailles. Le Hameau (The Hamlet), as it’s called, was (and still is!) a picture-perfect Norman style farm village, complete with thatched roofs and the usual barnyard animals. Marie-Antoinette would visit the grounds with her ladies-in-waiting, all dressed in rustic muslin dresses, in order to get away from court life and bask in the peasant ideal.

Photo: Bree Moon

A century later, Gossin Freres and Jacquier designed and produced Arcadian garden figures that looked to be straight off Marie Antoinette’s farm. As classically-trained sculptors whose work won medals at the 1877 Paris Salon, the Gossin brothers, Louis and Etienne, were no doubt familiar with traditional Arcadian imagery. The Gossin and Jacquier catalogs are filled with pastoral characters just like those in Watteau’s celebrated paintings. Indeed, our Marquis and Marquise are “fêtes galantes” in sculpted form–at first glance a whimsical pair, but suggestive, too, of the profound respect for Arcadia and the pastoral ideals it embodied.