Amidst the Quiet Verdure of the Field: An Introduction to America’s First Major Cemeteries

by Eva Schwartz

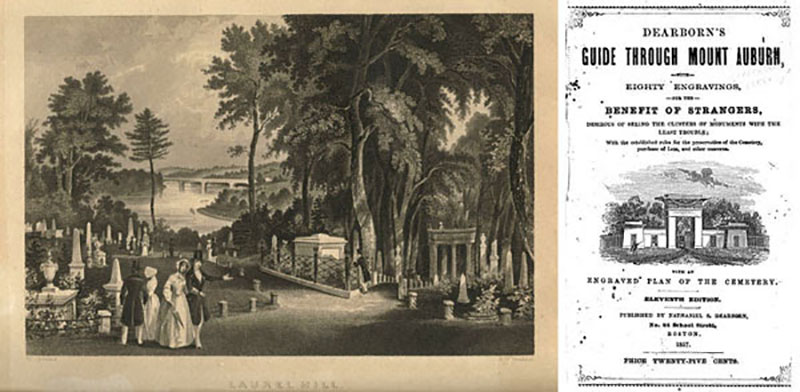

Our nation’s first urban parks were the “rural” cemeteries that took shape in the 1830s–among them Boston’s Mount Auburn (1831), Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill (1836) and New York’s Green-Wood (1838). These spacious and beautiful sites were first created as the antidote to the overcrowded and unhealthful conditions of the cities’ church graveyards. But the legacy of these first rural cemeteries is so much more than just a solution to the problem; these grounds established the importance–the necessity–of making green space open and accessible to all. These transformative cemeteries became the models for the purely recreational parks that came decades later; including New York’s Central Park, completed in 1873. [Image: Thomas Chambers (1808-1875), Mount Auburn Cemetery, Collection of the National Gallery of Art (Public Domain), via Wikimedia Commons]

Providing a bucolic respite from the rigors of city life, Mount Auburn, Laurel Hill, and Green-Wood (with many, many others modeled after them) were recreation sites suitable for picnics, carriage riding, leisurely strolls and family jaunts. They were not viewed as morbid or depressing, but rather were seen as picturesque destination spots, attracting tourists by the thousands. Cemeteries also became places for moral contemplation and, even, spiritual elevation. Contemporary critics and visionary landscape professionals like Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) advocated passionately for the creation of these public, urban green spaces as a means of lifting people up, preventing the slide into squalor that was associated with city living. [Please see article on Andrew Jackson Downing in our Hudson Valley issue of Focal Points, which can be found on our website, for a further discussion of the “Picturesque”, art as it relates to landscape, and the influence of British thinkers like John Claudius Loudon on the urban parks movement in America.]

[Images: “Laurel Hill”, A.W. Graham, engraver, The Library Company of Philadelphia, Appeared in March 1844 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book; Nathaniel Dearborn, Dearborn’s Guide Through Mount Auburn (Public Domain), via Wikimedia Commons]Americas-Cemeteries-06.

The idea of Mount Auburn Cemetery, the first of its kind in America, had been batted around for some years before finally being pushed to realization by the renowned Boston physician and part-time botanist Jacob Bigelow (1787-1879). As a medical doctor, Bigelow was naturally concerned with the health risks posed by congested graveyards, but as a scholar of horticulture he was perhaps even more taken with the potential restorative power of a public rural cemetery.

Between 1825 and 1831, when Mount Auburn was officially dedicated, Jacob Bigelow was the leading champion of its creation and one of the main consultants to supervising designer, Henry A.S. Dearborn (1783-1851). In an address given by Bigelow at an 1831 meeting of the Boston Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, a scholarly group of which he was a founding member, he emphasized the “joint influence of nature and art” that a rural cemetery would nurture:

In a few years, when the hand of taste shall have scattered among the trees…enduring memorials of marble and granite, a landscape of the most picturesque character will be created. No place in the environs of the city will possess stronger attractions for the visitor. This can be…done, not in the tumultuous and harassing din of the cities…but amidst the quiet verdure of the field…where the harmonious and ever-changing face of nature reminds us, by its resuscitating influences, that to die is but to live again.

Eighteen years later, when Bigelow’s plan for Mount Auburn had inarguably succeeded, Andrew Jackson Downing posited that it would inspire creation of public (non-cemetery) parks:

At the present moment, there is scarcely a city of note in the whole country that has not its rural cemetery…. If the road to Mount Auburn is now lined with coaches, continually carrying inhabitants of Boston by thousands and tens of thousands, is it not likely that such a garden, full of the most varied instruction, amusement, and recreation, would be ten times more visited? —The Horticulturalist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, July 1849

So it was that Mount Auburn and its successors sparked a revolution in thinking–a revolution that lead to some of the country’s most prized public parks.

A Stroll Through Mount Auburn

by Katy Keiffer

Last November by some great good fortune we found ourselves in Boston on business with a few free hours. A visit to Mount Auburn Cemetery seemed like the most gratifying way to spend that beautiful autumn day. When we walked through the North Entrance we admired a massive copper beech and as we progressed along the paths we found ourselves just as taken by the foliage as we were by the monuments. [All photos by Katy Keiffer and Sylvia Falcón]

Last November by some great good fortune we found ourselves in Boston on business with a few free hours. A visit to Mount Auburn Cemetery seemed like the most gratifying way to spend that beautiful autumn day. When we walked through the North Entrance we admired a massive copper beech and as we progressed along the paths we found ourselves just as taken by the foliage as we were by the monuments. [All photos by Katy Keiffer and Sylvia Falcón]

Mount Auburn is perhaps the most extensively planted of the American cemeteries that were designed as much for public enjoyment as for public interment. Literally thousands of mature trees and shrubs are massed on the grounds, including flora from all over the world. With collections of flowering trees, massive shade trees, ornamental evergreens and dwarf trees, for a dendrophile there is no time of year that fails to satisfy. Best of all, nearly all the trees bear identification tags that include the species name and country of origin and, sometimes, the dated planted, allowing the visitor to note their favorites and dream of creating their own arboretum.

Mount Auburn is perhaps the most extensively planted of the American cemeteries that were designed as much for public enjoyment as for public interment. Literally thousands of mature trees and shrubs are massed on the grounds, including flora from all over the world. With collections of flowering trees, massive shade trees, ornamental evergreens and dwarf trees, for a dendrophile there is no time of year that fails to satisfy. Best of all, nearly all the trees bear identification tags that include the species name and country of origin and, sometimes, the dated planted, allowing the visitor to note their favorites and dream of creating their own arboretum.

When we there, most of the deciduous trees had shed their leaves but the Japanese maples, of which there are nearly 80 specimens of various cultivars, were blazing in an astonishing display of flame colors.

Even the trees that were bare were remarkable for their mature shapes and bark. We were thrilled by the gigantic specimens of paper and golden birch. There were many sugar maples whose natural forms were so much more interesting minus their leaves. The specimens of weeping and copper beech trees were perhaps the most magnificent, however. Enormous, perfectly shaped and cared for, they exemplified the nobility of the genus and lent real grandeur to the views.

Even the trees that were bare were remarkable for their mature shapes and bark. We were thrilled by the gigantic specimens of paper and golden birch. There were many sugar maples whose natural forms were so much more interesting minus their leaves. The specimens of weeping and copper beech trees were perhaps the most magnificent, however. Enormous, perfectly shaped and cared for, they exemplified the nobility of the genus and lent real grandeur to the views.

Mount Auburn has grown to approximately 175 acres of undulating landscape and includes a natural amphitheater in the center of the cemetery known as The Dell, lakes Halcyon and Auburn, and Willow Pond; it’s no wonder it remains a popular place to visit. And we were among the many people walking the grounds just as they did when the cemetery was consecrated in 1831–there was even a group taking sun in front of Mary Baker Eddy’s memorial on Halcyon Lake.

Click here to see an aerial map that illustrates the lushness of the Mount Auburn scheme. To learn more about Mount Auburn visit their website.

Click here to see an aerial map that illustrates the lushness of the Mount Auburn scheme. To learn more about Mount Auburn visit their website.

A final note: we only realized as were going to press that written permission was required to post our own images taken at Mount Auburn. With this in mind we have endeavored to obscure the names on headstones that appear in our photos of the grounds and trust this satisfies the spirit of Mount Auburn’s guidelines regarding photography for public distribution.

My Search for Sargent’s Grave

by Barbara Israel

On my last trip to England I decided to visit the famed Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey in order to better understand the relationship between 19th-century landscaped cemeteries and the later ornamented private gardens of America. An added benefit would be that one of my artistic heroes, John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), was buried there and I could look for his (presumably impressive) gravestone.

On my last trip to England I decided to visit the famed Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey in order to better understand the relationship between 19th-century landscaped cemeteries and the later ornamented private gardens of America. An added benefit would be that one of my artistic heroes, John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), was buried there and I could look for his (presumably impressive) gravestone.

The history of Brookwood, opened in 1854, is rich with tales chronicling the lives of those interred there. Statesmen, scholars, Titanic survivors, businessmen, criminals and even a king or two from countries around the world are Brookwood’s permanent residents. Brookwood is also known by the mildly disturbing title “The London Necropolis”. This refers to its origin as the first out-of-town place for interments after in-town burial space ran out. Trains carried the coffined dead and their mourners from central London to two stations at Brookwood, the North for “non-conformists” and the South for Anglicans (Church of England). For quite a time Brookwood was the largest cemetery in Europe and remains one of the most renowned.

It’s an understatement to say that Brookwood is so large that it would be easy to get lost. When I started walking around I wondered if I’d ever find my car again! My first impression was of huge trees surrounding multitudes of crosses and statues marking gravesites. I had a map but wasn’t entirely sure where I was to begin with! The plots appeared to radiate out from a small circular plot so I started walking around on one of the paths.

It’s an understatement to say that Brookwood is so large that it would be easy to get lost. When I started walking around I wondered if I’d ever find my car again! My first impression was of huge trees surrounding multitudes of crosses and statues marking gravesites. I had a map but wasn’t entirely sure where I was to begin with! The plots appeared to radiate out from a small circular plot so I started walking around on one of the paths.

The most common memorial seemed to be the cross but my eye was drawn of course to figures and unusual forms. The grandest monuments were angels with massive wings stretching up to the heavens. I was particularly impressed by one such spectacular bronze sculpture facing a small alleé, a memorial to three members of the Bart family.

There were very few seats or benches anywhere but occasional rustic style structures that I was later able to identify as “lychgates”. For those unfamiliar with the term, these are roofed gateways designating the entrance to English/English-style churchyards (one is depicted below). This particular rustic look has been replicated in many English and American gardens. It originated with the natural or “landscape” gardens of 18th-century England and brought with it “Rustic” style furniture where their parts simulated branches. The Rustic look was very much in vogue at the close of the 19th century in American gardens and cemeteries, exemplified by the numerous marble tomb ornaments carved to look like wood (at left is an example found in New York City’s Trinity Church Cemetery). Furniture made in late 19th-century France using an innovative and meticulous technique of layering cement atop a metal armature to create life-like branches, the classic “faux bois” method, is still sought-after by designers today. In among the rustic elements at Brookwood were a number of classical and even Egyptian Revival style mausoleums, reminding me that divergent influences can happily co-exist in a garden setting.

There were very few seats or benches anywhere but occasional rustic style structures that I was later able to identify as “lychgates”. For those unfamiliar with the term, these are roofed gateways designating the entrance to English/English-style churchyards (one is depicted below). This particular rustic look has been replicated in many English and American gardens. It originated with the natural or “landscape” gardens of 18th-century England and brought with it “Rustic” style furniture where their parts simulated branches. The Rustic look was very much in vogue at the close of the 19th century in American gardens and cemeteries, exemplified by the numerous marble tomb ornaments carved to look like wood (at left is an example found in New York City’s Trinity Church Cemetery). Furniture made in late 19th-century France using an innovative and meticulous technique of layering cement atop a metal armature to create life-like branches, the classic “faux bois” method, is still sought-after by designers today. In among the rustic elements at Brookwood were a number of classical and even Egyptian Revival style mausoleums, reminding me that divergent influences can happily co-exist in a garden setting.

Some of the most interesting monuments were those with such symbols as anchors and ships. In funerary art the anchor was used, not in the maritime sense, but to signify hope for the departed soul. And indeed, in statuary forms of the Seven Virtues the figure of Hope is shown leaning on an anchor. In similar fashion a garden figure would have the identical attributes and symbolism. Another gravestone with a non-nautical connotation has a pilot-less ship guided by an angel at the bow implying that God was steering the soul’s journey.

I found another elaborate sculpture at the foot of a tomb depicting a helmet and plume, a laurel branch, medals and a purse. In this case the decorations did relate to the life of a soldier. He was a member of the 21st Empress of India’s Lancers (who wore helmets with white plumes) who served in the Nile Expedition and was “severely wounded” in the Battle of Khartoum in 1898.

I found another elaborate sculpture at the foot of a tomb depicting a helmet and plume, a laurel branch, medals and a purse. In this case the decorations did relate to the life of a soldier. He was a member of the 21st Empress of India’s Lancers (who wore helmets with white plumes) who served in the Nile Expedition and was “severely wounded” in the Battle of Khartoum in 1898.

But I’d been thoroughly distracted from my search for John Singer Sargent. I trotted off to inspect some large sculptures figuring he would have been significantly memorialized. What I found instead was a single entrance lychgate that lead to a small, concealed burial plot surrounded by woods with a commemorative cross at the center. I later learned that this choice section belonged to a single parish, that of St. Stephen’s of South Kensington and was exclusively for their parishioners.

Still hunting for Sargent I cam across the single finest statue in the entire cemetery. The memorial to Lord Edward (d. 1907) and Lady Matilda Jane Pelham-Clinton (d. 1892) is an enormous bronze with a grief-stricken figure bowing next to the body of the deceased watched over by a majestic angel. I could not help but notice that it was desperately in need of restoration, both the statue and the pedestal. It turns out this is one of Brookwood Cemetery’s “Listed Monuments”, submitted to the government’s Department of Culture, Media & Sports, and designated eligible for Brookwood to solicit outside funding to aid in its restoration. I am happy to know it’s recognized as highly important and will be looked after.

Still hunting for Sargent I cam across the single finest statue in the entire cemetery. The memorial to Lord Edward (d. 1907) and Lady Matilda Jane Pelham-Clinton (d. 1892) is an enormous bronze with a grief-stricken figure bowing next to the body of the deceased watched over by a majestic angel. I could not help but notice that it was desperately in need of restoration, both the statue and the pedestal. It turns out this is one of Brookwood Cemetery’s “Listed Monuments”, submitted to the government’s Department of Culture, Media & Sports, and designated eligible for Brookwood to solicit outside funding to aid in its restoration. I am happy to know it’s recognized as highly important and will be looked after.

Every time I turned around another glade of beautiful old trees appeared but one that stood out above all was a simple cross that was surrounded by four massive columnar trees.

I never found Sargent’s grave. If only I had thought to use my iPhone to do a Google search where he was buried I would have discovered it right under my nose. At the very center of the circle that I had been navigating around, standing in a plot known as The Ring, would have been the rather modest headstone marking the grave of John Singer Sargent and his sister Emily. Of course there are a number of websites with images of his stone. I like this one.

I never found Sargent’s grave. If only I had thought to use my iPhone to do a Google search where he was buried I would have discovered it right under my nose. At the very center of the circle that I had been navigating around, standing in a plot known as The Ring, would have been the rather modest headstone marking the grave of John Singer Sargent and his sister Emily. Of course there are a number of websites with images of his stone. I like this one.

Despite this disappointment, I was delighted to have spent the time exploring Brookwood. It was especially gratifying to see the sheer quality of the monuments. Clearly some of the finest 19th-century sculptors and stone masons were completing funerary commissions in addition to private gardens and civic works. And the park-like, pastoral aspect of the landscape confirmed that the Rural Cemetery movement had made as large an impact on England as it had in America.

Forever New York

by Katy Keiffer

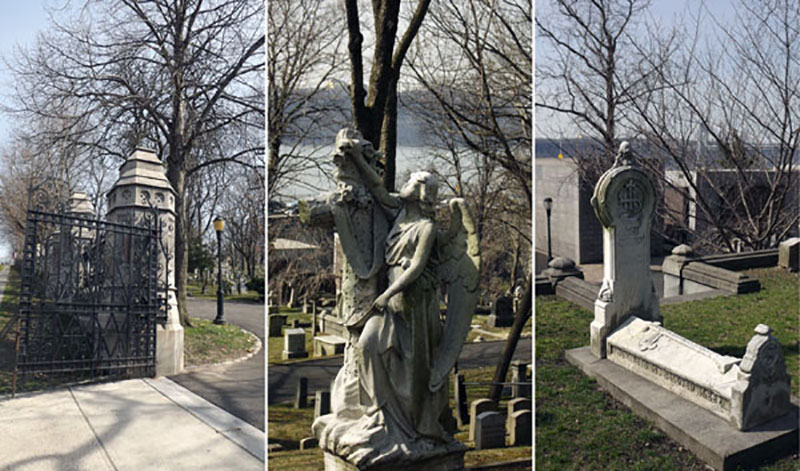

We chose to pay a visit to our local cemetery, Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum. Located in Washington Heights, between 153rd and 155th Streets, this cemetery is associated with Trinity Church in the Wall Street area. It was established in 1842, when the lower Manhattan churchyard was running out of space, on land that had been part of John James Audubon’s estate. It was designed by James Renwick Jr. (1818-1895), perhaps best known as the architect of St. Patrick’s Cathedral and the Smithsonian Institution Building (The Castle).

The cemetery is bounded on the east and west by Amsterdam Avenue and Riverside Drive, respectively, and has two sections divided by Broadway. It’s hilly location affords views of the George Washington Bridge (just visible through the trees in the right-hand phto) and the Palisades. Next door, between 155th and 156th Streets, is the Audubon Terrace building complex which includes The Hispanic Society of America and The American Academy of Arts and Letters, among other institutions. [All photos by Katy Keiffer, Eva Schwartz and Sylvia Falcón]

Because this cemetery is the final resting place of some very notable individuals, including members of the Astor family, Alfred Tennyson Dickens (1845-1912), son of Charles, and New York City Mayors Fernando Woods (1812-1881) and Ed Koch (1929-2013), there is much to offer the lay historian or genealogist. And speaking of genealogy, after our visit we discovered that Barbara’s great-great-grandfather John Adams Dix (1798-1879) is also buried here. Dix was a major-general in the Union army, a U.S. Senator, Secretary of the Treasury (1861), minister to France (1866-1869) and governor of New York (1873-1874). At the beginning of the Civil War while Secretary of the Treasury he wired Treasury agents in New Orleans with the orders to “shoot [anyone] on the spot” if they tried to take down the American flag. This sentiment struck a chord with the Union cause and tokens were privately minted with this charge. According to Wikipedia, the font of all knowledge: “Among the best-known varieties of patriotic tokens are the so-called ‘Dix tokens'”.

Fittingly, John James Audubon (1785-1851) is also buried here. Though it has been extensively documented we would be remiss if we didn’t include a few images of the impressive carving on the Audubon Memorial. In the form of a soaring Celtic cross it is carved front and back with images of birds and mammals. At the base is a portrait of Audubon and reliefs alluding to his roles as a naturalist and artist. Visit this site for details of how and why the Audubon Memorial came into existence. Also of interest, from March 21-May 26, 2014, The New York Historical Society will feature “Parts Unknown” the second of a three-part exhibition known collectively as Audubon’s Aviary: The Complete Flock. To learn more about this extraordinary exhibition visit the Future Exhibitions page on the Society’s website.

Barbara’s article featured a gravestone of a large anchor, a symbol of hope for the soul, and mentioned that the personification of Hope is always shown with an anchor. There is a beautiful depiction in Trinity with right arm raised and index finger pointing heavenward, her face upturned and crowned with a five-pointed star, another symbol of immortality. There were, in fact, many instances of anchors of which we’ve shown three examples.

Barbara’s article featured a gravestone of a large anchor, a symbol of hope for the soul, and mentioned that the personification of Hope is always shown with an anchor. There is a beautiful depiction in Trinity with right arm raised and index finger pointing heavenward, her face upturned and crowned with a five-pointed star, another symbol of immortality. There were, in fact, many instances of anchors of which we’ve shown three examples.

Other well-represented motifs at Trinity, noted in several forms and materials, were those of ivy and oak leaves. Ivy, because it is hardy and remains green year-round, can symbolize both fidelity and eternal life. Oak leaves (not depicted) are also a symbol of eternal life and, of course, strength. The obelisk-form monument, derived from Egyptian iconography representing a single ray of sun, is common in American cemeteries, and Trinity is no exception. The obelisk is yet another form associated with eternal life. Images centered more on loss and a life cut short are the broken bloom, the inverted torch and the draped urn surmounting a pedestal.

We’re so glad we decided to explore this repository of New York City history and it’s nice to know, since Trinity is the only remaining active cemetery in Manhattan, that we don’t have to leave our beloved borough…ever!