A Forgotten Part of a Once Forgotten Garden

By Barbara Israel

The lower gates at Untermyer Gardens. Photo: Bree Moon

At the very bottom of the hill at Untermyer Gardens in Yonkers, NY there are a series of gateposts, walls and gates comprising an impressive entranceway. In the past most visitors haven’t made the long trek down to see this part of the garden but recently new direct pathways have been opened up and have drawn our attention to this area. Set into the walls are two puzzling statuary reliefs that are of particular interest in terms of their meaning and origin.

Stories abound relating to the comings and goings of famous and infamous persons in this lower section of these gardens but our aim is to get beyond these tales and get to the heart of the design story. In other parts of the garden the architect/designer William Welles Bosworth (1869-1966), who was hired by Samuel Untermyer in 1916, borrowed lavishly from exotic architectural styles–referencing Persian, Spanish, Indian and Grecian elements while taking inspiration from renowned gardens. Bosworth’s plan for the lower section of the garden took inspiration from the original gates to the property, situated at the North Broadway entrance. Those gates, dating to the 1860s, were created for John Waring, the first owner of the Untermyer mansion.

At the end of the 19th century Bosworth had been trained in architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and thus brought with him the entire lexicon of its forms and elements. In 1906 John D. Rockefeller had hired Bosworth to transform the bare land around his house, Kykuit, in Pocantico Hills, NY into spectacular gardens. After visiting the Beaux-Arts gardens at Kykuit Untermyer hired Bosworth to design “the greatest gardens in the world” for his property in Yonkers.

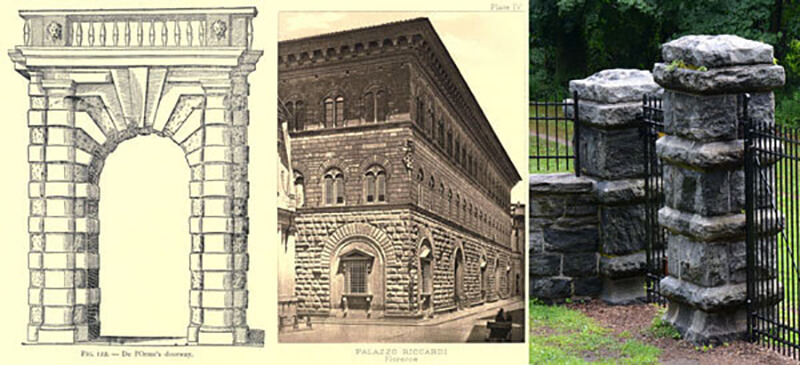

Left to right: A Renaissance period arch using rusticated piers; the Palazzo Riccardi, a period Renaissance palace that used a rusticated surface for the lower floor (illustrated in Charles Herbert Moore, Character of Renaissance Architecture, 1905, pp. 204 and 102); the rusticated columns at Untermyer’s lower entrance (photo: Bree Moon).

The Beaux-Arts style venerated and incorporated many Italian Renaissance architectural and decorative features. Here in the lower entrance he has made clear references to that style. For one, “rusticated” stone finishes were a popular feature for ground level walls of Beaux-Arts houses and he has used them liberally in the walls and gateposts. “Rustication” was a masonry technique in which blocks of stone were cut evenly at the edges but the faces of each block were given an intentionally rough surface.

Photo: Bree Moon

The Beaux-Arts idiom also included statuary; particularly such marble relief sculptures integrated into architecture as the two at the Untermyer lower gates (above). The lion to the right is easy to identify but, because of its missing head, the companion sculpture has been often misidentified as a horse. It is, in fact, a unicorn having the head and body of a horse, the head with a single spiral horn, and the legs of a female deer. In determining that the creature is in fact a unicorn the most potent clue is its cloven hoof; a detail that simply could not have belonged to a horse.

The Beaux-Arts idiom also included statuary; particularly such marble relief sculptures integrated into architecture as the two at the Untermyer lower gates (above). The lion to the right is easy to identify but, because of its missing head, the companion sculpture has been often misidentified as a horse. It is, in fact, a unicorn having the head and body of a horse, the head with a single spiral horn, and the legs of a female deer. In determining that the creature is in fact a unicorn the most potent clue is its cloven hoof; a detail that simply could not have belonged to a horse.

Photo: Bree Moon

By Sodacan (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] via Wikimedia Commons.

User: Jaqian [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Looking more closely at the sculptures in the wall it appears that the wall and openings were designed and sized to fit the two reliefs implying that they were acquired before the wall was built. But where did they come from? One story that has been passed down attributes them to Edward Clark Potter, the sculptor of the lions at the entrance of the New York Public Library. But, after some research we have found no resemblance to Potter’s style or workmanship and, at this point, no evidence of his having done this commission.

Historically, the lion and the unicorn have been a customary pair. They were thought to be antagonistic rivals and at times were accepted as symbols of the sun and the moon. The pairing of the two became most visible in 1603 with the accession of James I to the throne of Scotland, Ireland and England when he combined them in the Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (right).

A closer look at the Untermyer lion and unicorn has led us in one particular direction. They are reliefs of similar height with partially rendered bodies and are consciously looking over their shoulders. If they had come from a very large stone architectural Royal Coat of Arms from Great Britain they would be just as described above except that originally they would have been facing each other. They would have been on opposite sides than they are now with their heads turned toward the center looking at a crown or central motif, as depicted in the Irish Royal Coat of Arms on the Custom House in Dublin (right). The unicorns in architectural British coats of arms had bent knees and the regal lions have full manes like this one (and the two below). Like the two at Untermyer, the lion and unicorn would not have had fully rendered bodies; just the front half would have been sculpted.

Royal coats of arms, English, locations unknown; photos www.speel.me.uk.

If Bosworth had obtained them as salvaged fragments from a giant armorial shield from a demolished building he perhaps would have found it fitting to imbed them in a wall looking out at the garden. By changing their viewing directions outward instead of inward he adapted them to their new location. Another Beaux-Arts architect, Stanford White (1853-1906) had imported antique fragments from Europe by the boatload and popularized their use in gardens in the early 20th century. Even though White, having died in 1906, could never have been actively involved in providing statuary for Samuel Untermyer’s gardens his extraordinary taste and creativity had ripple effects long after his death. (For a discussion of White’s influence see Eva Schwartz’ article, “The Hurstmont Planter” in the Marble in America issue of Focal Points.)

Left: Untermyer Gardens English-style gates, 1937. Photo: Courtesy of the Hudson River Museum, Gift of Mrs. Karin R. Brophy, for Gordon S. Roberts, 96.4.2.

Right: Formal Beaux-Arts style forecourt gates at Kykuit, Pocantico Hills, NY designed by William Welles Bosworth after the gates at Hampton Court in England. Photo: Barbara Israel.

There are unquestionably a few answers to this overlooked lower part of the garden. The two sculptural reliefs, possibly fragments that began life atop a building in Great Britain, thematically fit into the whole lower garden concept of rusticated but refined symmetry. The wrought-iron entrance gates that we see in this archival picture of 1937 (above left) hark back to formal English style gates that had had their own antecedents on the Continent, specifically in the Renaissance. These have long since been removed and replaced. Note that the Untermyer unicorn seems to be missing its horn in this vintage photo. Perhaps the horn was missing when it was reclaimed and incorporated in the Untermyer Gardens lower entrance scheme. As he had done such commissions as Kykuit (above right), Bosworth designed a pair of wrought-iron gates that added to the formal stylistic statement. Appropriate to his Beaux-Arts training Bosworth chose to create a grand European style entrance for Samuel Untermyer with classical architectural details in the Renaissance tradition.

A Model for Stewardship: The Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park

By Eva Schwartz

Photo: Eva Schwartz.

When I planned a mini-vacation to Woodstock, VT last summer, I scoured lists of local attractions with the intention of visiting a historic garden and writing it up for Focal Points. Situated in Woodstock proper, the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park (Vermont’s only national park) was the clear choice. Photos online showed a handsome brick mansion and a charming–though small–formal flower garden with Italianate fountain and benches. I made plans to visit with my two boys, figuring it would be a pleasant and easy jaunt.

When we arrived, we were struck by the utter splendor of the place. Of course, the beauty wasn’t unexpected (if you’ve never been to this postcard-perfect village–it’s stunning), but the history of the site came as a surprise to me–and the best possible one, at that! Reading the stories of the visionary men and women who shaped this property and the surrounding land was profoundly moving. After only a short while, I knew I was in for much, much more than a garden tour.

Panoramic view of Woodstock, VT. Photo: guyvail [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

View of the Billings Farm and Museum looking southwest across the pastures. Photo: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, HALS VT-1-37.

We started our visit at the Billings Farm and Museum across the road from the mansion. Both entities were owned by Frederick Billings (1823-1890), a gifted lawyer, businessman, and environmental activist. Functioning since 1992 as both a working dairy farm and an education center (managed by The Woodstock Foundation, Inc., founded by Billings’ granddaughter, Mary French Rockefeller and husband, Laurance Rockefeller), it was one of many farms acquired by Billings in the 1870s in order to implement a statewide shift in farming–from sheep to mostly dairy cows. This purposeful change in the direction of farming in Vermont–spurred both by environmental concerns and by the recognition that eastern sheep raising had been overshadowed by increasingly powerful ranchers out west–was one of many innovations spearheaded by the forward-thinking Billings.

Photos: Eva Schwartz.

As my sons and I meandered through the Billings farmhouse, we were impressed by the smartly-appointed interiors. Billings had wanted his farmers to have the latest technology, so he supplied this farm (and others, I assume) with indoor toilets and plumbing, fancy gas lighting, and the most beautiful pantry I think I’ve ever seen. Even my 8-year-old remarked on the decorative sink basins and stately, though sensible, bathtub! Although the original furnishings had long since been removed, the curatorial staff has done a spectacular job of filling the house with period-appropriate pieces (Aesthetic Movement and Eastlake style), and I must say, it’s just glorious.

Photo: National Park Service.

I decided I wanted to know more about Frederick Billings. I found out that he wasn’t born in Woodstock, but considered himself a Woodstock man through and through, owing to the gracious welcome his family received when they arrived in 1835. The family had seen some bitterly hard times, and Frederick, perhaps more than anyone, was motivated to reverse their misfortune. Thus, in 1849, after studying law in Vermont, he set out to find prosperity in California. He opened an office in San Francisco, providing legal representation to Gold Rush stakeholders, and in so doing, swiftly gained the money and influence he had sought.

View of Yosemite Valley with Half Dome in the distance. Photo: Jon Sullivan, Public Domain.

While in California, he visited the spectacular site of what was to become Yosemite National Park, and it’s no exaggeration to say that it changed his life. He felt so committed to the majesty of the landscape, and to the idea that it never be ravaged by human beings, that he became one of the country’s leading champions of environmentalism and the national parks movement. This passion and respect for the natural world would profoundly influence his decision-making in the following years.

Photo by Matthew Brady, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-109923.

In addition to inspiring a lifelong dedication to land preservation, the magnificence of Yosemite led Billings to read a most important work titled Man and Nature; or Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action (1864), written by a fellow Woodstock resident, the utterly brilliant linguist, statesman, foreign ambassador, farmer, manufacturer, and, above all, ecologist, George Perkins Marsh (1801-1882). This book, now considered the first American treatise on environmental conservation, made a colossal impact on Billings. Billings had first heard George Marsh’s ideas at a meeting of the Agricultural Society of Rutland County (VT) in 1847 (on one of Billings’ visits East), where Marsh had floated a wildly-visionary concept of a national ecological system–including a sweeping forestry program–and had stressed the critical need for environmental protection. Marsh’s influence was felt early on; in 1849 Billings wrote from San Francisco that the settlers there were so fanatical about striking gold, they’d barely care if “no blade of grass survive[d]”.

Returning to live in Woodstock in 1869, Billings brought with him the energy and ingenuity gained from years in the west, and the determination to make a difference in his home state. Upon his arrival, he found that the house built by George Perkins Marsh’s father, Charles Marsh, was up for sale, so he quickly bought it. [Charles Marsh (1765-1849), was a prominent lawyer who served as United States Congressman and as District Attorney for the state of Vermont.] The Marsh property–one of the finest in Woodstock-had long been admired by Billings, but this wasn’t a simple case of wish fulfillment. In taking stewardship of the Marsh family farm, Billings had taken a stand to honor and broaden the legacy of the admirable George Perkins Marsh.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, HALS VT-50.

Marsh’s influential Man and Nature, revolutionized the way people thought about their effect on the natural world and on the planet as a whole. The book garnered public attention from the very start; it was widely read and upon Marsh’s death was celebrated for having exposed a subject “so abstruse, so vast, and so complex” as to be without rival. (Bennett Hubbard Nash and Francis Philip Nash, “Notice of George Perkins Marsh”, American Association for the Advancement of Science Proceedings, 1882-83.) His intention in writing it, as Marsh noted in a letter to then-Secretary of State William H. Seward was “to show the evils resulting from too much clearing and cultivation, and [other] so-called improvements”. Marsh understood, on an observational but also intuitive level, the havoc that humans had, and would, inflict upon the environment.

Marsh certainly felt an abiding kinship with nature. He wrote that he was “forest-born” and identified with “the bubbling brook, the trees, the flowers, the wild animals…as persons, not things”. He remarked that as a child he had “sympathized with those beings, as [he had] never done since with the general society of men, too many of whom would find it hard to make out as good a claim to personality as a respectable oak”. This affinity for the forest was born, in large part, from having grown up at the base of Mount Tom (where the Marsh property is situated in Woodstock), and from having been raised by a father who truly appreciated the joys of nature. Marsh recounted that as a very young boy he would sit in a carriage between his father’s knees, and to his mind, “the whole earth lay spread out before [him]”. The elder Marsh “pointed out the most striking trees as [they] passed… and told [him] how to distinguish their varieties”. His father “called [his] attention to the general configuration” of the land and to the way water gathered at the tops of hills and ran down the sides. This was George Marsh’s early introduction to the existence of a watershed, and the genesis of the idea that rainfall, rivers, lakes, plants, trees, roots, erosion and animal life were all intricately interdependent.

When George Marsh was a child, his beloved Mount Tom and the surrounding area had already endured more than thirty years of clear-cutting, which had transformed much of the valley from forest to pasture and farm fields. The uppermost reaches of the mountain had also been affected by rampant clearing, which had led to erosion and a loss of the vital microclimates nourished by forest cover. The general feeling of the day was that these changes were to be celebrated (or, at least, pardoned), as they were the beneficent work of man–transformation in the interest of civilization. But as both a lifelong nature sympathizer and as an actual contributor to the everyday degradation of the forest (as he himself owned mills, raised sheep, and sold lumber), Marsh observed early on the recklessness of that way of thinking. Between the time of his birth and his departure for Italy in 1861 (where he would, while serving as Minister to Italy, write Men and Nature), Marsh had seen the woodlands of Vermont reduced by half, and the toll was rising.

So, when Frederick Billings took over the property in 1869, his first priority, taking heed of Marsh’s warnings, was, literally, to replant the forest. This task he undertook with precision, scrutiny, and with an eye towards creating a sustainable working forest. Billings’ wife, Julia, wrote that “he was led to consider forestry by reading the writings of Geo. P. Marsh regarding climatic changes induced by devastation of the forests; and he thought the farmers should be taught to see the importance of preserving their woodlands. He found out what trees were best adapted to the climate [even researching and introducing non-native European species] and then set them out by the…thousands. His example has caused many farmers there to plant trees on the barren hillsides and has therefore proved very valuable”.

One of Billings’ carriage roads. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, HAER VT, 14-WOOD, 9.52.

Beyond reforestation, Billings created a working, managed woodland with far-reaching educational and research implications. He created twenty miles of carriage roads, both to support the progressive forestry techniques employed at the site, and to provide recreational trails and vista points for local residents. The Vermont Standard newspaper reported in 1886 that “the carriage roads…are romantic in the extreme. Mr. Billings has always kept the gates wide open for the public to enjoy with him these beautiful drives”. In this way, Billings won over the average leisure-seeker by making them experience firsthand the critical conservation work he had undertaken. To this day, this 555-acre national historic park is one of the oldest and largest managed forests in the country, and the only one devoted to telling the story of land conservation and stewardship.

Frederick Billings’ educational aims were further propelled by the innovations he made at Billings Farm. In addition to technological trailblazing, Billings researched and imported a premiere breed of British Jersey cows in order to improve longevity of the herd. The shift from sheep-raising to cows and dairy production, which was to have lasting reverberations in the state, was a conservation-minded move, as grazing sheep depleted resources more aggressively than grazing cows. Today, as a working farm and museum, Billings’ ideas for sustainable farming continue to inspire modern-day agricultural innovators.

Reading the placards and literature at the Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller visitors’ center, I was deeply moved by the history of the place. And that was before I’d had a chance to explore the tidy, charming formal garden there at the house–the one I’d ostensibly come to see! In 1869 Billings hired

Robert Morris Copeland (1830-1874), a Boston-based landscape architect and urban planner, to design the mansion grounds. Copeland had published a very practical book in 1859 called Country Life: A Handbook of Agriculture, Horticulture, and Landscape Gardening. In it he offered tips on planting, construction of greenhouses, irrigation, kitchen gardens and the like. He also rather boldly criticized the great Andrew Jackson Downing’s instructions on how to achieve pleasing, naturalistic plantings, so we know he had strong opinions! Copeland’s feeling was that landscape designers should study and replicate the sorts of plant and tree groupings found in nature. Those natural groupings, having arisen independent of human meddling, were to be commended and imitated. Copeland advised his readers that “if [critics] condemn your efforts to reproduce Nature and to imitate her profuse, graceful, and irregular variety, they are simply to be pitied, and their comments are to be despised”.

At the Billings house, Copeland’s plantings and groupings of trees certainly achieved the kind of naturalistic, aspirational beauty he sought. Of particular appeal are the gently sloped terraces on the mansion grounds that successfully create little pocket vistas. There’s a grandeur to the space that cannot be properly described. Copeland did not, however, have a hand in the formal garden; this was the work of Charles Platt (1861-1933), hired by Julia Billings years after Frederick’s death.

The formal garden dates to 1899 and is indicative of Platt’s penchant for Italian design. He had traveled to Italy in 1892 to study and document surviving gardens of the Italian Renaissance. His subsequent publication, the massively influential Italian Gardens (1894), was responsible, along with Edith Wharton’s Italian Villas and their Gardens (1904), for ushering in an era of Italianate garden design in the United States. From the Marsh-Billings mansion and visitors’ center, my boys and I walked up to the formal garden–up because it’s on one of Copeland’s terraced levels–and the first thing we noticed was a classical marble tazza fountain, ornamented with grotesque masks, so typical for the period. The garden itself has a symmetrical square plan, with the fountain as the central element, and simple, classically-styled marble benches placed at the outside edges. The plantings, profuse and colorful and bursting on the July day we saw them, were beautifully contained in four quadrants.

Photos: Eva Schwartz

While the bones and ornaments of the garden are as Platt left them, the plantings within the quadrants have been redesigned through the years. Ellen Biddle Shipman (1869-1950), one of the great landscape architects of the twentieth century, and one of the first female practitioners to achieve national prominence, changed the formal plantings in 1912-1913. Shipman was a close colleague of Platt’s, and is often seen as Platt’s protégé, though her expertise in horticulture far surpassed his. Julia Billings also hired another pioneering female landscape architect, Martha Brooks Hutcheson (1871-1959), to create a formal entry circle on the property. Hutcheson, one of the first women to attend the fledgling landscape architecture program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, completed dozens of commissions, but very little of her work remains (thank goodness her driveway circle does!).

Photos: Eva Schwartz

The formal garden’s current color scheme (bright, of primary hues) is in keeping with the flowers put in by Mary Rockefeller in the 1950s. Mary French, the granddaughter of Frederick and Julia Billings, married Laurance Rockefeller in 1934, and inherited the Marsh-Billings property in the 1950s. The Rockefellers carried on the legacy established by the visionary George Perkins Marsh and Frederick Billings, carefully and skillfully protecting the progressive practices of those two forward-thinkers. In 1992, the property was gifted to the National Park Service to continue its educational mission. That this one tract of land, one system of gardens, carriage roads, forest, and pasture, should have been touched by even one great thinker–that would have been incredible. The fact that Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park was transformed and sustained by so many illustrious, enlightened thinkers and doers–this is something to be cherished. I know it’s a place I’ll come back to again and again.

Notes on quotes: All George Perkins Marsh quotes cited in David Lowenthal, George Perkins Marsh, Prophet of Conservation, University of Washington Press (Seattle: 2000).

All Frederick and Julia Billings quotes cited in Jane Curtis, et al., Frederick Billings, Vermonter, Pioneer Lawyer, Business Man, Conservationist, Woodstock Foundation (Woodstock, VT: 1986).