Marble Ornaments from Hurstmont

By Barbara Israel

On the morning of February 10th, 2011 I was sent photos of some ornaments for sale at a house in New Jersey. Our contact said that they were at a house that had been redesigned in 1902 by Stanford White (1853-1906) of McKim, Mead and White. And it was important that I come right away. I don’t know what it takes to motivate most people but for me all this was like a red flag to a bull. The name Stanford White, the legendary, scandalous architect designer of America’s Gilded Age tycoons, inspired me to immediate action!

I hopped right in the car. Well, not quite. I got to my garage and and was told the elevator was broken, so I couldn’t get my car out of its underground lot. Yikes! I knew my husband had signed up for Zipcar so I thought I’d take that. I got a reservation and raced to a nearby garage only to find that there was a special card I had to have. DISASTER. I’m not sure if it was my persuasiveness or my desperation, but eventually I got a car. Suffice it to say that if I hadn’t been totally determined to get there it wouldn’t have happened. The seller wanted a decision by the next day so I would have gotten there if I’d had to ride a bike. Oh, I forgot to mention we’d just had a blizzard the day before and the world was deep in snow. And if I were to purchase the pieces they had to be moved right away! At least I remembered to wear my boots.

I hopped right in the car. Well, not quite. I got to my garage and and was told the elevator was broken, so I couldn’t get my car out of its underground lot. Yikes! I knew my husband had signed up for Zipcar so I thought I’d take that. I got a reservation and raced to a nearby garage only to find that there was a special card I had to have. DISASTER. I’m not sure if it was my persuasiveness or my desperation, but eventually I got a car. Suffice it to say that if I hadn’t been totally determined to get there it wouldn’t have happened. The seller wanted a decision by the next day so I would have gotten there if I’d had to ride a bike. Oh, I forgot to mention we’d just had a blizzard the day before and the world was deep in snow. And if I were to purchase the pieces they had to be moved right away! At least I remembered to wear my boots.

Rationally, none of it sounded very promising, or plausible, but something compelled me ahead. I had been told that the house, called “Hurstmont”, was in Harding Township (near where I’d grown up) and that James Tolman Pyle had owned it in its heyday. When I got there the house itself looked to be long forgotten but with good “bones”. Stanford White’s characteristic two-story columns were there. I was met by my contact and he first showed me the flat marble bench by the door. With rust stains… not easy to remove. Then we wandered over to the urn–the enormous urn (above). It appeared to be in very rough shape, but the scale of it was impressive. I thought it looked like a replica of the Antique Medici Vase. Interest started to grow.

We then took a long walk through a sunken garden and way around to another end of the property. And there in front of me was a huge sarcophagus-form planter (right) with the most extraordinary carving I’d seen in all my years in business! I said then and there that I was very interested in buying the three pieces.

We then took a long walk through a sunken garden and way around to another end of the property. And there in front of me was a huge sarcophagus-form planter (right) with the most extraordinary carving I’d seen in all my years in business! I said then and there that I was very interested in buying the three pieces.

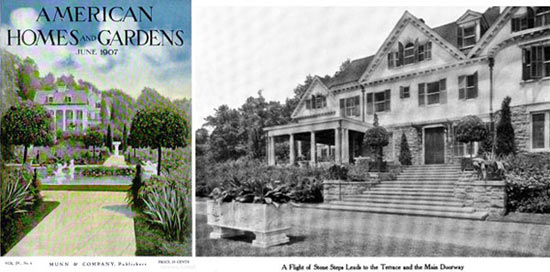

All three pieces were shown to great acclaim at the 2012 Winter Antiques Show. As often happens at the 10-day show someone came in with an in-depth interest in what we were exhibiting, in this case, the pieces from Hurstmont. This gentleman was very excited to see that the ornaments had been saved and that very night he emailed me a digitized version of the June 1907 issue of American Homes and Gardens that featured Hurstmont inside and on its cover! When I had seen the house last February it was in derelict condition so the 1907 photos of the property totally surprised me. It had been a spectacular property with an enormous formal garden. Of course the most exciting discovery was seeing each ornament as it had originally been used. The sarcophagus-style planter had been filled

with tropicals and placed directly opposite the entrance to the house (above). The urn was pictured in place next to the house (not shown) and in tribute to the urn’s size (80 inches high) and weight (4,500 pounds), it was exactly where I’d found it 104 years later. [Digitized version, from which we obtained the above two images, available for online viewing through Google eBooks]

The historical photos show many more ornaments on the property, most of which had disappeared over the years. My personal theory is that the three remaining pieces were too large and heavy to be easily sold or stolen. The article mentions that there were a number of flat marble benches like the one I bought. Stanford White likely commissioned them in Italy specifically for the Pyle garden.

Cleaned and Restored UrnThe prominent landscape architect Daniel W. Langton (1864-1909), who lived out his life on an adjoining property, designed the garden but probably was not responsible for providing the ornaments. My helpful source had also sent me photocopies of a book called Glen Alpin by Barbara Brennan on Hurstmont and Glen Alpin, its neighboring property. One of the photos shows how vast, formal and important the original Langton layout was.

The Hurstmont adventure turned out to be far more interesting than I ever could have imagined. Sadly, a developer had bought the house and is turning it into condos. I guess that means demolition. That makes these ornaments and the pictures of Hurstmont and its gardens all the more significant as testament of how Americans lived in the Gilded Age.

A Closer Look: The Hurstmont Planter

A Closer Look: The Hurstmont Planter

By Eva Schwartz

When Barbara received photographs of three marble ornaments at a 1902-03 Stanford White estate called Hurstmont she wasn’t immediately sold on them, but she had a feeling she should see them in person. As soon as she did, she knew she had to have them–even though at the time they were covered with snow and in need of significant conservation work. The quality of the carving and the tremendous size of the pieces would have been reasons enough to buy them, but the association with the illustrious Stanford White made them all the more enticing. The subsequent acquisition of those pieces–a sarcophagus-form planter (right), a bench and a massive replica of the Medici Vase–led to a flurry of questions about their origins. We knew we had another exciting research project ahead.

When examining the Hurstmont pieces, we felt confident that the bench and vase dated to the nineteenth century, but we wondered if the sarcophagus-style planter could have been Roman. Ornaments made to mimic something else–in this case an ancient Roman sarcophagus–can be confounding, and when it comes to the authentication of antiquities, we happily turn to other experts. Our auction gallery friends in England felt it was a nineteenth-century replica, and a rather faithful one. Still, we thought we should probe further. Following the purchase of these pieces, we bought a book by Peter Rockwell called The Compleat Marble Sleuth (2004), an invaluable resource for anyone interested in the history of marble working. We were so taken with the book for its gorgeous comparative photographs and readable text that we decided, on a whim, to contact the author. Peter Rockwell had lived and sculpted in Rome for decades, and had lectured extensively on the history of stonecarving, so he was the ideal person to shed some light on our enigmatic sarcophagus.

Rockwell graciously answered our query and had much to say about this piece. He concluded in his correspondence that it was a very high-quality nineteenth-century reproduction, likely produced for the export market. The carving style on the front face is exactly in the manner of ancient Roman production; however, several characteristics reveal its later date. First, the “Romans never carved out the interior so neatly. [It is] finished with a flat chisel whereas the interiors of Roman sarcophagi were carved with a point chisel”. Second, the front and back faces are two different styles of bas relief, and Rockwell had never seen such a thing on an authentic Roman sarcophagus. Proper Roman sarcophagi never had any carving on the back face as they were meant to be placed against a tomb wall. Moreover, according to Rockwell, the architectural background seen on the back face (below) is not at all in keeping with true Roman pieces. He also noted that on Roman examples he would normally see evidence of the use of a type of drill called the strap drill, or cord drill, “for example, in the figure’s hair,” but on our sarcophagus he did not.

Feeling satisfied with a nineteenth-century attribution, we turned to explore the Stanford White connection. White, a partner in the legendary architectural firm McKim, Mead and White, was a gifted classicist with an astute eye for collecting. We had for years been fascinated by the objects he had chosen for his own garden at Box Hill, in St. James, Long Island–an assemblage of ancient-looking relics, term figures, oil jars, columns and urns–all skillfully arranged to look like a chanced-upon ruin. The below photos of Box Hill were supplied by White’s great-grandson, Samuel White.

Box Hill South Lawn ca. 1903

Box Hill Garden ca. 1902

Since by all accounts the Hurstmont pieces had been at the house since Stanford White’s days–and as they were certainly the type of ornaments he generally acquired–we thought there might be some documentation that would prove his procurement of them. We contacted the esteemed Wayne Craven, Professor of Art History, Emeritus, at the University of Delaware, and author of Stanford White: Decorator in Opulence and Dealer in Antiquities (2005). This publication gives a vibrant picture of White’s genius and his acquisitiveness, describing whirlwind European shopping excursions, and elucidating relationships with prominent (and sometimes infamous) antique dealers.

Craven’s book makes clear a rather important point: that Stanford White was comfortable with buying reproductions, as long as the seller represented them as such and the price was right. It was the look of the object that appealed to him most, not its authenticity or prestigious provenance. Craven writes that

White was not a collector in the sense that Henry Clay Frick was, or Henry Huntington or J. Pierpont Morgan–men who were committed to the formation of collections of only the most superb, unquestioned masterworks by the most famous artists. At times, it seems more accurate to say that White was more a “gatherer” than a collector, searching for decorative pieces that would work well in a patron’s salon, library, or billiard room

(Craven, 70).

Joseph Duveen (1869-1939), the influential British art dealer who helped build the collections of many of America’s Gilded Age luminaries, once wrote to White that he and his associates would “never guarantee any marbles from Italy as 99 pieces out of 100 are made up”(Craven 70). Thus, in the case of the marble sarcophagus, White would not have been troubled that it wasn’t truly Antique, nor would it have bothered him that it wasn’t an academically-correct replica. It mattered much more that it made stylistic sense for the house, endowing the garden with the spirit of an ancient relic. It was ornamented on all sides (adding to its usability), and offered plenty of space for plantings.

Although Professor Craven had not done any work specific to Hurstmont, he corroborated our supposition that the marble ornaments had been purchased by White on a buying trip in Italy. Sadly, he didn’t know of any existing documents relating to the pieces, so we contacted Janet Foster, Associate Director of Urban Planning and Historic Preservation at Columbia University. She had a particular interest in Hurstmont, having lectured on the subject. She revealed that while there were files pertaining to the estate at Columbia’s Avery Library and at the New York Historical Society, there was no information as far as she knew on the garden ornament. She, too, felt that the Hurstmont pieces were in keeping with those typically acquired by Stanford White.

Stanford White’s own collection of marble ornaments, listed in a 1907 catalog of the sale of his estate, confirms his enthusiasm for a great range of objects. Catalogued therein are two sarcophagi, eighty-three architectural fragments, nine urns, four fountains, seven statuary fragments and ten oil jars, among numerous other items, many of these no doubt slated for use in either his garden or a client’s. They were certainly a testament to his love for classical relics and the inventive way he used them in his design schemes. We can’t help but wonder if more of them would have landed at Hurstmont, if Stanford White hadn’t met such an early and unfortunate end.

Marble in America: Part I, The Industry

Marble in America: Part I, The Industry

By Eva Schwartz

The acquisition of the marble ornaments from Hurstmont inspired us to delve into their specific history but also brought to the fore a number of broader questions about the marble industry. Whenever we find late nineteenth-century marble objects in the Italianate syle, we speculate as to whether they were made in Italy or made in America by Italian craftsmen. Was there a way to determine the origin of the workmanship, not to mention the stone? For all the work we had done in the field, we still had much to learn about the American marble industry, its development, and its facets.

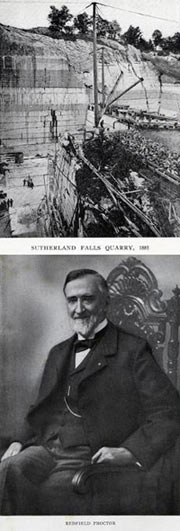

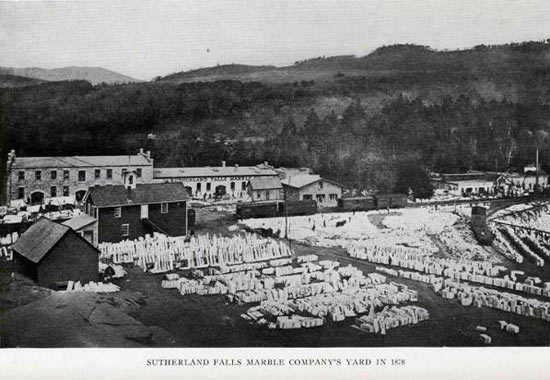

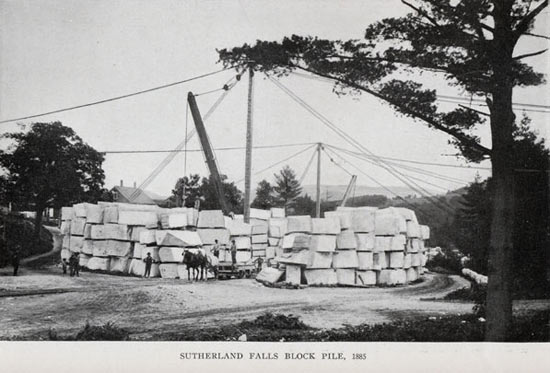

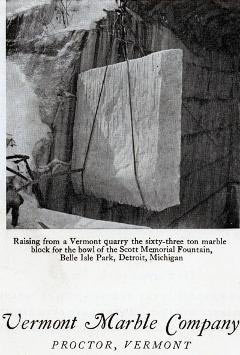

We decided to start with the Vermont Marble Company, the long-lived firm that became the most poweful force in the American marble trade. Marble was first quarried in Vermont in the late eighteenth century and used for mantlepieces, headstones, and other small-scale pieces. By the 1830s, the government of Vermont staked much importance on the future of marble quarrying in the state, leading their congressional representatives in 1832 to seek a law that would protect Vermont marble interests from foreign competition. At that time, there were a number of scattered quarries, none of them booming businesses. But in 1869, Redfield Proctor (1831-1908) stepped forward with the drive and vision that would transform the industry. Proctor, a Vermont-bred lawyer and businessman and later politician, assumed directorship of the struggling Sutherland Falls Marble Company and charted a historic course for expansion and success. It 1880, after a decade of pioneering, the Sutherland Falls concern was incorporated as the Vermont Marble Company. Proctor also created a partnership–called the Producers Marble Company–with several other marble outfits, which would have tested the limits of today’s anti-trust laws; it required all members to pay in to a pot controlled overwhelmingly by Proctor’s firm. Even after the partnership dissolved at the end of 1887, the Vermont Marble Company remained the dominant establishment, often buying out its competitors when they failed.

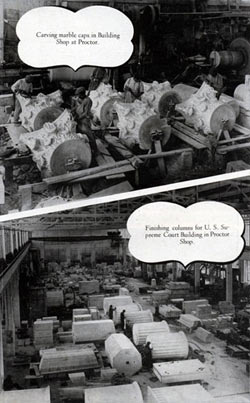

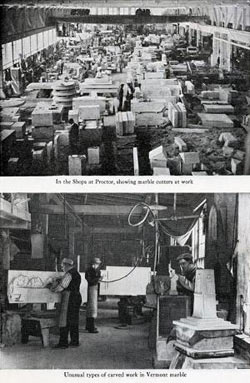

The original Sutherland Falls Marble Company produced sawed blocks for monumental uses, but did not do any of the finishing that would become the Vermont Marble Company’s mainstay. The finishing shop/mill opened in 1880. It was no coincidence that in the same year, Redfield Proctor convinced five Italian marble carvers to leave Carrara and emigrate to Vermont. This small, but significant, influx then prompted, over several years, at least two thousand Italian marble workers to relocate to the Green Mountain state. As a group, these experienced artisans were vital to the transformation of Vermont Marble from a bulk supplier into a first-class finishing company. And the transformation included a broader range of products. Whereas the early focus was on monuments alone, by World War I, sixty percent of the firm’s business came from finished interior building materials.

The first branch of the firm opened in Toledo, Ohio in about 1875; by 1886, there were 11 branches nationwide. Meanwhile, the firm acquired quarries across the country, so it was no longer selling marble solely from Vermont. By the early 1920s, the strategy of efficient management, growth, and marketing that Redfield Proctor had set in motion had paid off; at that time, the firm owned more than 75 quarries and was producing more than one million cubic feet of sawed marble annually. Indeed, the first few decades of the twentieth century were boom years for the Vermont Marble Company, in that its marble was used for some of nation’s most iconic monuments and buildings, including the main branch of the New York Public Library, the amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery, the Red Cross headquarters, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Supreme Court building in Washington, DC.

The first branch of the firm opened in Toledo, Ohio in about 1875; by 1886, there were 11 branches nationwide. Meanwhile, the firm acquired quarries across the country, so it was no longer selling marble solely from Vermont. By the early 1920s, the strategy of efficient management, growth, and marketing that Redfield Proctor had set in motion had paid off; at that time, the firm owned more than 75 quarries and was producing more than one million cubic feet of sawed marble annually. Indeed, the first few decades of the twentieth century were boom years for the Vermont Marble Company, in that its marble was used for some of nation’s most iconic monuments and buildings, including the main branch of the New York Public Library, the amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery, the Red Cross headquarters, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Supreme Court building in Washington, DC.

The enormous success of the Vermont Marble Company was a marvel in and of itself, but was especially important within the greater context of the American-Italian marble trade. Long before Redfield Proctor entered the business, Vermont was seen as the epicenter of the American marble industry. In The Marble-Workers’ Manual, a practical handbook of 1856, M. L. Booth asserted that “Vermont is the Marble State, and this material will prove one of its most fruitful sources of wealth”. However, even Booth questioned whether Vermont marble could ever trump the cachet of Carrara:

At West Rutland, statuary Marble is quarried that is surpassed by none in the world. Our own sculptors have availed themselves of it to some extent, and some orders for it from Italian sculptors at Rome have been filled. It is said to be of a finer grain, to work more easily than the foreign, and not to crumble so badly under the chisel. (Booth, 245-6) But notwithstanding the abundance of our home supply, very much of that used for interior ornamentation is imported….For some purposes the foreign may be a better article, or if not better, it is better known. Then there is still some prejudice, perhaps, in favor of an imported material, on the part of the uninformed.

(Booth 252)

Booth also cited domestic marble to be more expensive for the American buyer than imported marble–probably owing to nascent production methods–and posited that the cost negatively affected its saleability [it must be noted that later sources made the case that imported marbles were much more costly for the consumer than American]. A review of Booth’s book in the January 1857 issue of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science and Art, is pointedly critical of the continued dependence on Carrara and applauds Booth’s inclusion of a list of fine American marbles. The article concludes that the American building industry “continue[s], however, to depend upon Carrara–having paid last year two hundred and thirty thousand dollars for foreign marbles. We note, as two crumbs of comfort…that the quarries of Vermont yield annually a round million of dollars”.

Booth also cited domestic marble to be more expensive for the American buyer than imported marble–probably owing to nascent production methods–and posited that the cost negatively affected its saleability [it must be noted that later sources made the case that imported marbles were much more costly for the consumer than American]. A review of Booth’s book in the January 1857 issue of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science and Art, is pointedly critical of the continued dependence on Carrara and applauds Booth’s inclusion of a list of fine American marbles. The article concludes that the American building industry “continue[s], however, to depend upon Carrara–having paid last year two hundred and thirty thousand dollars for foreign marbles. We note, as two crumbs of comfort…that the quarries of Vermont yield annually a round million of dollars”.

Two advertisements printed a few years earlier in the January 15th and 16th, 1852 editions of the New York Evening Post support the idea that Italian products had tremendous marketability among East Coast buyers. A Mr. Ottaviana Gori of 893 Broadway in New York City, promoted his

elegant collection of Berloni niche and garden figures, of the most desirable subjects and exquisite artistic workmanship…Also, two splendid marble lions, after Canova, just imported. [We have just] erected…an improved powerful steam engine…now enabled to execute all orders in [our] line with the utmost dispatch…all from original designs of [our] own…procuring the marble in the rough, direct from the quarries.

The ad copy is cryptic to us now in that it does not indicate the origin of the rough marble (was it imported from Carrara, or was it domestically sourced?) but it does specify that some of the finished products were imported, while some were produced on site. Either way, as an Italian craftsman living and working in the United States, Mr. Gori seems to have understood that a connection with Old World Italy would have greatly appealed to his American clients.

As there were so many opinions offered by contemporary writers on the subject of American versus Italian marble, it is difficult to get a clear picture of the industry at the time. By the late nineteeth century, American production had increased greatly since the time of M. L. Booth’s 1856 Manual, but some writers did not have the faith Booth had had in the superior quality of the material. A November 1888 article titled “American Marbles” in The Manufacturer and Builder, noted that “the marble industry of Rutland [Vermont] has been a prosperous one, and at the present time it is calculated that some 2,000 men find employment in the quarries, mills, and workshops. Rutland statuary [marble] is said to be too soft for ordinary purposes…The marble is certainly not so easy to work as that of Italy; it is what is called ‘plucky’–that is, given to breaking away before the chisel, unless great care is used”.

As there were so many opinions offered by contemporary writers on the subject of American versus Italian marble, it is difficult to get a clear picture of the industry at the time. By the late nineteeth century, American production had increased greatly since the time of M. L. Booth’s 1856 Manual, but some writers did not have the faith Booth had had in the superior quality of the material. A November 1888 article titled “American Marbles” in The Manufacturer and Builder, noted that “the marble industry of Rutland [Vermont] has been a prosperous one, and at the present time it is calculated that some 2,000 men find employment in the quarries, mills, and workshops. Rutland statuary [marble] is said to be too soft for ordinary purposes…The marble is certainly not so easy to work as that of Italy; it is what is called ‘plucky’–that is, given to breaking away before the chisel, unless great care is used”.

Another article titled “Foreign vs. American Marbles”, in the October 1891 issue of The Manufacturer and Builder, criticized trade professionals for the insufficient championing of domestic marble. In that piece, the author, George P. Merrill, made an example of the Equitable Building in Baltimore, the city’s first skyscraper, constructed in 1891. He took issue with the Baltimore Sun’s announcement that the Equitable’s architects would travel to “the marble quarries of Italy, Belgium, and France to select fancy marbles for the interior decoration of the…building”. Merrill used the news of the voyage as a call to arms, arguing that Americans could do a better job of developing their own marbles. He contended that “the coming exposition in Chicago [The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition] will doubtless [afford] an opportunity for a display of our native products, and it is to be hoped the management will place the matter in the hands of some responsible agent who can be relied upon to make the most of it”.

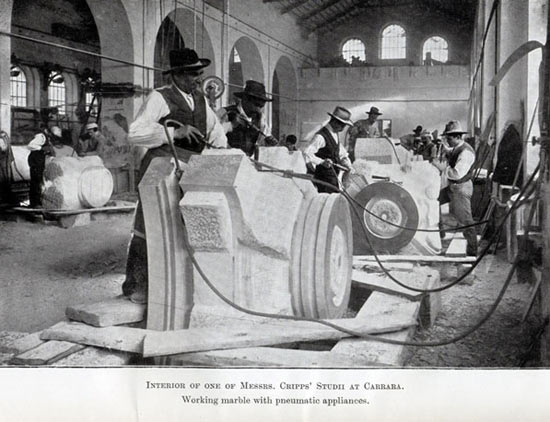

Other writers asserted that America could never live up to the quality of Italian marble, and certainly not to the expertise of the Italian carvers. In “Carrara”, a piece published in the trade publication, The Monumental News, in March 1893, the author proclaimed that “without doubt the finest workers in marble in the world” were in Carrara. The article further noted that “at least two generations must pass before statuary, for example, can be made in any other country as cheaply as in Italy….They [the Italian marble carvers] are required to spend from eight to ten years in the Academy of Fine Arts, which is one of the best in Europe under government control, and the better workmen do not find it necessary to emigrate”. Thus, according to this source, the best artisans were not leaving Italy for America, though we know in truth that a great many of them did. Notably, the same article gives credit to American dealers for being instrumental players in the Italian marble industry, confirming what we knew about the vast number of marble ornaments being exported for American clients.

Other writers asserted that America could never live up to the quality of Italian marble, and certainly not to the expertise of the Italian carvers. In “Carrara”, a piece published in the trade publication, The Monumental News, in March 1893, the author proclaimed that “without doubt the finest workers in marble in the world” were in Carrara. The article further noted that “at least two generations must pass before statuary, for example, can be made in any other country as cheaply as in Italy….They [the Italian marble carvers] are required to spend from eight to ten years in the Academy of Fine Arts, which is one of the best in Europe under government control, and the better workmen do not find it necessary to emigrate”. Thus, according to this source, the best artisans were not leaving Italy for America, though we know in truth that a great many of them did. Notably, the same article gives credit to American dealers for being instrumental players in the Italian marble industry, confirming what we knew about the vast number of marble ornaments being exported for American clients.

A 1909 book titled Marble and Marble Working by W. G. Renwick (London: Crosby, Lockwood and Son) is useful in fleshing out the import/export aspects of the American marble industry. In 1909, Redfield Proctor had recently died, and his enormously successful Vermont Marble Company had been growing steadily for forty years. Renwick, a British writer, attributed a good deal of that success to the Dingley Tariff Act of 1897. This Act, effective from 1897-1909, was the longest-lived and most severely protectionist tariff act in United States history, raising tariff rates to the highest-ever level of 52%. It was President William McKinley’s effort to protect American industry from foreign competition, an endeavor that began with the McKinley Tariff of 1890, passed when he was a representative in Congress. According to W. G. Renwick, the import tariffs on foreign marble gave “considerable impetus to the quarrying industry…[and] special encouragement to the working both of American and imported marbles in America”. In 1909 the tariff on rough blocks of marble brought into the country was sixty-five cents per cubic foot and the tariff on worked/finished marbles even higher–all to the apparent benefit of domestic producers. Renwick proclaimed the “Green Mountains of Vermont [to be] the most prolific of American marble fields” and he estimated that the productivity of American quarries as a whole had increased “thirty-fold” in just a decade.

On the state of marble finishing in America, Renwick offered contradictory information, perhaps owing to the fact that he was not as familiar with the American industry as he was with the British. At one point in the text, Renwick asserted that “the working of marble, apart from building and monumental purposes, could hardly be said to exist. Several of the principal decorative schemes in leading cities were carried through by the New York branch of a prominent London firm (Burke & Co.) who obtained the greater part of their marble, worked ready for fixing, from an equally prominent Belgian house”. Later, it is stated that “marble is used in the United States for building purposes to a very large extent; but the decorative trade is now a large and increasing one, and, since the tariff came into force, but few instances of imported worked marble other than works of antiquity are on record”. One has to wonder how the statement “the working of marble…could hardly be said to exist [in America]” could be reconciled with the contention that there were “few instances of imported worked marble on record”. Renwick went on to claim that the tariffs had succeeded in blocking the importation of most worked marble, “securing employment for American work-people rather than those of another country”. This assertion seems to be completely untrue, considering that we know that European immigrants were coming in great numbers to work at the quarries [unless he was considering foreign-born workers in America as American?].

The 1910 Census report for Marble, Colorado, home of the Colorado Yule Marble Quarry, a major competitor of the Vermont Marble Company at the time (later owned by Vermont Marble), illustrates the predominance of foreign workers at American quarries. In that year, of the marble workers in Marble, Colorado, 110 were American-born and 179 were foreign-born. And 124 of the 179 foreign workers were Italian, with all of those countrymen employed in the higher-skilled mill positions, not in the quarries.

One of the most telling late-nineteenth century sources is Rowland E. Robinson’s “In the Marble Hills”, published in the September 1890 issue of Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. In this article, Rowland quotes Redfield Proctor, having contacted him for opinions on the current state of the marble trade. Even with the expected self-promotion, Proctor’s perspective on marble statuary, offered in an 1885 letter to Rowland, is particularly insightful:

We export very little marble for statuary purposes. Most of the American sculptors either reside in Italy or have their work done there, not on account of the marble, but on account of the skilled workmen; and of course they would naturally use that marble if it was as good as American. I think the best of the Italian is better for statuary that is to be kept within doors, because it is a little harder and can be cut to finer lines; but though harder than the Rutland white marble, for some cause not yet fully understood no Italian marble will stand exposure to the weather in any climate as well as the American…The amount of [Vermont Marble Company] marble used for statuary purposes is very insignificant. It is of no commercial importance whatever…Mr. Mead [Larkin Goldsmith Mead, 1835-1910] and Mr. Powers [likely Preston Powers, 1842-1904, son of the better known Hiram Powers] have both expressed to me the highest opinion of Vermont marble for statuary purposes, but they must have men to do the work from their designs who have been trained to the business from youth, and they could find no such men in this country.

Proctor’s acknowledgment that the top American sculptors continued to work with carvers in Italy indicates that he did not yet have an operation with the sort of depth and reputation that would have served their needs. Proctor further noted that the statuary produced by the Vermont Marble Company was usually crafted for ecclesiastical purposes. Even today, the only Vermont Marble Company-era maquettes in the possession of The Vermont Marble Museum, the institution housed in some of the firm’s original Proctor, VT buildings, are of religious figures. It makes good sense, of course, that a company that specialized early on in cemetery monuments and memorials would have expanded into religious statuary. And while it would seem that garden statuary and ornaments would be a natural next step, we have not yet found evidence that Vermont Marble was regularly producing ready-made garden pieces until the very end of the 1920s.

» Continue Reading: Marble in America: Part II