A Touch of Italy in the Berkshires

by Barbara Israel

Visiting The Mount, the Lenox, MA home of Edith Wharton (1862-1937), is a particular delight. My husband Tom and I went with the New York Society Library tour that included the house and garden. Needless to say, it was the garden that captured my attention.

Visiting The Mount, the Lenox, MA home of Edith Wharton (1862-1937), is a particular delight. My husband Tom and I went with the New York Society Library tour that included the house and garden. Needless to say, it was the garden that captured my attention.

In February 1901 Wharton purchased the original 113 acres; the present property is 49.5 acres. Construction seems to have progressed smoothly as Wharton was able to move into The Mount in September 1902, but by some accounts it wasn’t finished until 1905. Sadly, Wharton lived at The Mount for a comparatively brief time. In 1911 she separated from her husband and decided to sell the property.

An interesting anecdote is the derivation of the name. One would think it came by its name because the main house was situated on the highest ground; in fact, Wharton appropriated the name from her ancestor, Ebenezer Stevens (1751-1823). Stevens, a Revolutionary War hero, became a successful New York City merchant and built a country house on Long Island that he named Mount Buonaparte (note the Italian spelling), but when Napoleon was crowned emperor, “the republican Stevens, in disgust, renamed his house ‘The Mount,’ a name his great-granddaughter would borrow.” (Hermione Lee, Edith Wharton, 2007)

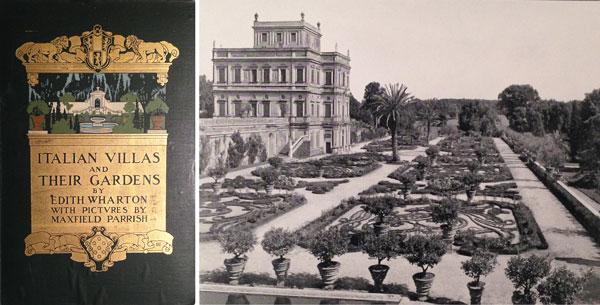

Presumably while working on the design of her garden at The Mount, Wharton was also writing her highly influential book Italian Villas and their Gardens; it came out in 1904. And, it is important to remember that Charles A. Platt (1861-1933), the architect and landscape designer, had published his book Italian Gardens in 1894, and it had created an enormous interest in Italy and its gardens. Both books became THE tastemaker powerhouses of the early 20th century establishing a passion for all things Italianate. [Photos: Cover of 1904 edition; photograph of “Parterres on Terrace, Villa Belrespiro (Pamphily-Doria), Rome, Italian Villas and their Gardens, p. 116]

In her “Introduction” to Italian Villas and their Gardens, Wharton ends with an admonition to the prospective garden designer to go beyond a literal re-creation and be guided by “Not this or that amputated statue, or broken bas-relief, or fragmentary effect of any sort, but a sense of the informing spirit [emphasis added]-an understanding of the gardener’s purpose, and of the uses to which he meant his garden to be put.” (p. 13)

As our group approached The Mount I wondered, “to what extent will Wharton’s garden conform to the principles of the early Italian garden design outlined in her book?” Of course it would be a smaller space than most of the grand ones that she had seen but had she been successful in transporting the “spirit” itself? One of the things that I had had to learn when I first ventured warily into the field of garden ornament was that an understanding of historical design was essential. Little did I know then that had I simply read Wharton’s “Introduction” I would have had a clear and immediate idea of the attributes and character of the formal 16th to the 18th-century Italian garden.

As we walked out of the house I was struck by the sight of a host of conical evergreens standing like orderly soldiers guarding long stretches of green hedge (top right). Were these examples of what she had written about? Yes, I later found her words “Italian garden enchantment was not dependent on flowers” but the “mere combination of clipped green and stonework.” (p. 6) She also made it clear that flowers in a hot climate would have been hard to cultivate so the logical choice had been a simpler option.

The tour then took us to the right into a shady and private walled, sunken garden. Symmetrical beds had been softened with puffy plants at the edges. In the center was a quiet, round pool capped with a rustic style fountain made up of rocks. We were some distance from the house at this point and her words “each step away from architecture was a nearer approach to nature” (p. 12) indicate what she wanted to accomplish here. In the book she mentions that a thoughtful Italian garden designer often provided a shady place as a respite from the hot sun. The overhanging trees and the high stonework walls served the purpose of bathing this garden in shade. Besides, the rough stones that make up the arched walls around the sunken garden speak volumes about her taste for the “Old World” look. She even mentions admiring an Italian “colonnaded loggia” (p. 85) that provides even more shade for the visitor.

The tour then took us to the right into a shady and private walled, sunken garden. Symmetrical beds had been softened with puffy plants at the edges. In the center was a quiet, round pool capped with a rustic style fountain made up of rocks. We were some distance from the house at this point and her words “each step away from architecture was a nearer approach to nature” (p. 12) indicate what she wanted to accomplish here. In the book she mentions that a thoughtful Italian garden designer often provided a shady place as a respite from the hot sun. The overhanging trees and the high stonework walls served the purpose of bathing this garden in shade. Besides, the rough stones that make up the arched walls around the sunken garden speak volumes about her taste for the “Old World” look. She even mentions admiring an Italian “colonnaded loggia” (p. 85) that provides even more shade for the visitor.

We turned to look back at the house. It appeared enormous, particularly as it had been placed on the highest part of the property and we were at the lowest. And, again, this is consistent with her words that Italian villas “were always built on a hillside.” (p. 4) You will note that, other than classical details, the house itself bears little resemblance to an Italian villa. The garden, however, is another story as we noticed upon climbing out of the quiet tranquility of the sunken scheme.

We turned to look back at the house. It appeared enormous, particularly as it had been placed on the highest part of the property and we were at the lowest. And, again, this is consistent with her words that Italian villas “were always built on a hillside.” (p. 4) You will note that, other than classical details, the house itself bears little resemblance to an Italian villa. The garden, however, is another story as we noticed upon climbing out of the quiet tranquility of the sunken scheme.

As we stepped up we encountered two extensive columns of trees that had been clipped into virtual walls. I found out later that they were pleached (meaning branches had been interwoven) lime trees. Here indeed are Wharton’s “long ilex-walks” (p. 8), a typical hallmark of the Italian garden that were “not dependent on flowers” and also “independent of the seasons” (p. 5). The elongated unadorned path between the lines of sheltering trees eventually led us to another geometrical garden known as the “flower garden” or “parterre”. This part of the garden owes more to the French tradition than to the Italian, and speaks to the melding of styles that was popular in the States.

Here, white pathways crisscrossed the space giving sharp definition to the squared off beds of green. The rectangular garden, edged with perennials, had four L-shaped beds and a small fountain pool in the center. An arched trellis echoed a rounded grotto on axis in the sunken garden. Wharton’s words in her book are consistent with the layout of her own garden, “The inherent beauty of the [Italian] garden lies in the grouping of its parts-in the converging lines of its long ilex-walks, the alternation of sunny open spaces with cool woodland shade, the proportion between terrace and bowling green…” (p. 8) Symmetrical and formal following the Italianate tradition but not overly so as Wharton must have been aware that this was not a palatial estate.

Without question my favorite feature was the grass steps that I discovered as we turned to walk back up to the house. Taking the green theme to the limit the wide but low steps had been entirely incorporated into the lawn. The treads were thoroughly covered by grass and the only indication that these were stairs were the dark linear shadows of the risers. I found myself wondering-even though Italian gardens did not have all the dead heading that would have come with massive amounts of flowers how about the trimming and pruning of all the “clipped green” elements?

Without question my favorite feature was the grass steps that I discovered as we turned to walk back up to the house. Taking the green theme to the limit the wide but low steps had been entirely incorporated into the lawn. The treads were thoroughly covered by grass and the only indication that these were stairs were the dark linear shadows of the risers. I found myself wondering-even though Italian gardens did not have all the dead heading that would have come with massive amounts of flowers how about the trimming and pruning of all the “clipped green” elements?

As we had viewed the garden at The Mount I was certainly aware of its foreign formal antecedents but until I had studied Wharton’s book I had not fully realized the extent to which she had gone to assimilate the finest attributes of the early Italian garden. Through this book Italian Villas and their Gardens she helped inspire a true revival of interest in the formal Italianate style.

As we had viewed the garden at The Mount I was certainly aware of its foreign formal antecedents but until I had studied Wharton’s book I had not fully realized the extent to which she had gone to assimilate the finest attributes of the early Italian garden. Through this book Italian Villas and their Gardens she helped inspire a true revival of interest in the formal Italianate style.

An Uncommon Woman

An Uncommon Woman

by Katy Keiffer

We visited the New York Botanical Garden at the tail end of their multi-part exhibition “Groundbreakers: Great American Gardens and the Women Who Designed Them” (May 17 – September 7, 2014). The six “groundbreakers” are the landscape designers Marian Coffin (featured in our next article), Beatrix Farrand, and Ellen Shipman and the garden photographers Jessie Tarbox Beals, Mattie Edwards Hewitt, and Frances Benjamin Johnson, all of whom helped define American landscape design at the beginning of the 20th century.

Sadly, we arrived too late in the day to visit the “Groundbreakers” exhibits in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library. One of these, “Gardens for a Beautiful America: The Women who Photographed Them” featured the garden photography of Beals, Hewitt and Johnston, and primary source material such as vintage glass slides and publications illustrated with their photographs. The curator of this exhibition, Sam Watters, is also the author of the 2012 publication Gardens for a Beautiful America 1895-1935: Photographs by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Here’s a link to an interview with Sam Watters illustrated with some of Johnston’s photographs.

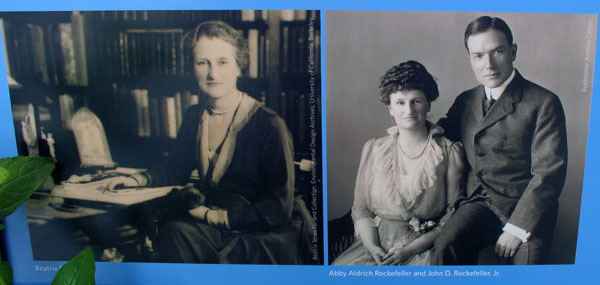

What we saw, in the Botanical Garden’s Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, was a remarkable recreation of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s garden at The Eyrie, her summer home, designed by Beatrix Farrand (1872-1959) beginning in 1926.

We arrived near the Botanical Garden’s closing time and so were the lone visitors to the exhibit. Thus the experience of walking amidst the flowers flanking the Conservatory’s central passage and on into the chamber housing the Moon Gate, with its Asian-influenced plantings, felt authentic, as if we were actually at Seal Harbor, having a cocktail walk before dinner!

Among the flowers were placards that displayed excerpts of letters between Farrand and Abby and John D. Jr. that speak to an affectionate and successful collaboration over a period of many years. Included was this charming quote that demonstrates Farrand’s dedication to, and appreciation of her clients, “…I am almost ashamed of spending as much time in your garden as I have done, but it is frankly so absorbing my thoughts, and it will be such a joy if it can be made a success and happiness to you and Mrs. Rockefeller, that I am throwing myself into the work with my whole heart.”

Born to a privileged family, Beatrix Farrand was a niece of Edith Wharton. Wharton was immensely helpful to her niece as she started out, introducing her to powerful and influential patrons. Her initial success was so marked that in 1899 when the American Society of Landscape Architects was founded, she was the only female founding member.

Heavily influenced by her travels to Europe and by the seminal gardens designed by Gertrude Jekyll, the Botanical Garden’s exhibit demonstrates Farrand’s philosophy toward form and color. Incorporating a wide array of perennials and annuals, the driving principal was the balancing of warm and cool hues with contrasting accents that make all the colors pop. While the plants featured were not identical to those in the actual Rockefeller garden, they proposed a similar style and scheme. Among the many species we saw in early September were: Larkspur, Zinnia, Gaillardia, Nicotinana, Dahlia, and Autumn Joy. The plants were massed in color groups and shapes, forming “a riot of color…” as Mrs. Rockefeller described it in her correspondence. In addition to enhancing the landscape, the flowers in the Rockefellers’ garden were destined for the some 70 vases throughout their house, and would have been swapped out continuously as the season advanced.

Heavily influenced by her travels to Europe and by the seminal gardens designed by Gertrude Jekyll, the Botanical Garden’s exhibit demonstrates Farrand’s philosophy toward form and color. Incorporating a wide array of perennials and annuals, the driving principal was the balancing of warm and cool hues with contrasting accents that make all the colors pop. While the plants featured were not identical to those in the actual Rockefeller garden, they proposed a similar style and scheme. Among the many species we saw in early September were: Larkspur, Zinnia, Gaillardia, Nicotinana, Dahlia, and Autumn Joy. The plants were massed in color groups and shapes, forming “a riot of color…” as Mrs. Rockefeller described it in her correspondence. In addition to enhancing the landscape, the flowers in the Rockefellers’ garden were destined for the some 70 vases throughout their house, and would have been swapped out continuously as the season advanced.

Though she had never been to the Far East, Farrand, nevertheless, designed a garden around the Moon Gate, a pink stucco wall with a perfectly round opening, inspired by the Rockefellers’ 1921 trip to Asia. Placed at the end of the formal garden, it was set within a shade garden with a walkway called the “Spirit Path”, which displayed Korean stone tomb figures. In September the blooms included masses of Japanese Anemone, Clivia, Cleome, Dusty Miller, Cinnamon Fern, and a variety of evergreens. Asian in character, the garden remained true to Ferrand’s love of native plants.

The seminal designs of Ferrand and her sister “groundbreakers” have been the source of inspiration for generations of American gardeners. So many of our great public gardens and spaces owe their beauty to the vision created by these remarkable women.

To learn more about Beatrix Farrand, visit the website of The Beatrix Farrand Society.

Beauty Required: An Introduction to Marian Cruger Coffin

Beauty Required: An Introduction to Marian Cruger Coffin

by Eva Schwartz

Landscape architect Marian Cruger Coffin (1876-1957) is often lauded for being among the first influential female landscape architects in America, but her legacy has more to do with the brilliance of her work than the fact that she happened to be a woman. Coffin, along with her contemporaries, Beatrix Farrand (1872-1959) and Ellen Biddle Shipman (1869-1950), entered the field not only because she had artistic aspirations, but also because it was one of the few professions open to women, and one of even fewer that permitted women to compete as equals with men. Along with more than 100 private estate commissions, including Winterthur, the Henry Francis du Pont estate in Wilmington, DE, Coffin served for 34 years as the University of Delaware’s landscape architect. Throughout her career, she was holistic in her attention to the design of the client’s entire property, not just to the dedicated garden spaces. More than half a century after her death, we feel the lasting impact of Coffin’s work, despite the inherent ephemerality of the gardens she created. [Photo: M. Coffin, ca. 1956, courtesy The Winterthur Library: Winterthur Archives]

Marian Coffin came from a privileged background, as had Farrand and Shipman, which afforded her advantages when it came time to connect with wealthy clients. Her client list reads as a who’s who of upper crust society, including the du Pont family, Marjorie Merriweather Post, and Childs Frick. However, her success was not an accident of birth, and she had to have had guts to become, in 1901, one of just four women out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s 500-member student body. Her application to the school was particularly courageous considering that she had only been home-tutored to that point and did not have the prerequisites required for admission! Much of Coffin’s tenacity also stemmed from necessity; her father died when she was only seven, leaving her and her mother, Alice Cruger Coffin, with no source of income. They moved in with Alice’s affluent relatives, who gave Marian a childhood of luxury, but later on she and her mother would have to make their own way. The family’s social connections, most importantly a long-standing friendship with the du Ponts, certainly opened the door for Marian Coffin; it was up to her to make good on the opportunity. [Photo: Undated, courtesy Geneva Historical Society, Geneva, NY]

Marian Coffin came from a privileged background, as had Farrand and Shipman, which afforded her advantages when it came time to connect with wealthy clients. Her client list reads as a who’s who of upper crust society, including the du Pont family, Marjorie Merriweather Post, and Childs Frick. However, her success was not an accident of birth, and she had to have had guts to become, in 1901, one of just four women out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s 500-member student body. Her application to the school was particularly courageous considering that she had only been home-tutored to that point and did not have the prerequisites required for admission! Much of Coffin’s tenacity also stemmed from necessity; her father died when she was only seven, leaving her and her mother, Alice Cruger Coffin, with no source of income. They moved in with Alice’s affluent relatives, who gave Marian a childhood of luxury, but later on she and her mother would have to make their own way. The family’s social connections, most importantly a long-standing friendship with the du Ponts, certainly opened the door for Marian Coffin; it was up to her to make good on the opportunity. [Photo: Undated, courtesy Geneva Historical Society, Geneva, NY]

Marian Coffin attended M.I.T. from 1901 to 1904. While there, she studiously absorbed the tenets of garden making under the tutelage of Guy Lowell (1870-1927), the director of the university’s landscape architecture department and the renowned author of American Gardens (1902). Lowell championed a return to more structured, geometric garden schemes, a reaction to the rustic, naturalistic style made famous in the States by landscape architects Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) and Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903). But while Lowell  favored the formal flowerbeds of English and French origin, he noted and encouraged the spin that American gardeners had put on standard parterres. Americans, he found, tended to pair plants in an unusual, more daring way, and they often let plants grow more wildly within their formal schemes, in contrast to the Europeans’ fastidiousness. Marian Coffin ascribed to this approach as well, offering up garden beds that were formal and classically Italian in spirit, yet nontraditional in the use of plantings and color. Yes, there were age-old garden elements, like allées, axial arrangements, and reflecting pools, but Coffin’s use of color and plant placement was wholly modern. [Photos: M.I.T., ca. 1901, courtesy Shorpy.com; Detail of Charles H. Sabin’s Southampton, NY garden, designed by Coffin, from Augusta Owen Patterson, American Homes of To-Day, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1924]

favored the formal flowerbeds of English and French origin, he noted and encouraged the spin that American gardeners had put on standard parterres. Americans, he found, tended to pair plants in an unusual, more daring way, and they often let plants grow more wildly within their formal schemes, in contrast to the Europeans’ fastidiousness. Marian Coffin ascribed to this approach as well, offering up garden beds that were formal and classically Italian in spirit, yet nontraditional in the use of plantings and color. Yes, there were age-old garden elements, like allées, axial arrangements, and reflecting pools, but Coffin’s use of color and plant placement was wholly modern. [Photos: M.I.T., ca. 1901, courtesy Shorpy.com; Detail of Charles H. Sabin’s Southampton, NY garden, designed by Coffin, from Augusta Owen Patterson, American Homes of To-Day, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1924]

An insightful article titled “The Garden Colorists”, published in The Architectural Record in July 1922–when Marian Coffin’s career was already well established-deftly  compares Coffin, Farrand, and Shipman to Impressionist painters. The author, Belinda Gerry, recalls the then-old-fashioned approach to planting flowerbeds, often referred to as “bedding out”, whereby plants of one variety were massed together to produce single-color displays. In response to that outdated technique, Gerry notes, “there has come into existence a school of garden colorists that, consciously or otherwise, is adopting and adapting the idea of impressionistic painting to floral planting. They are demonstrating the garden flowers arranged in close juxtaposition of color will produce, not kaleidoscopic polychrome effects, but [an] amalgamation [of related, but not identical hues]”. [Photo: Example of bedding out courtesy Humphrey Bolton, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

compares Coffin, Farrand, and Shipman to Impressionist painters. The author, Belinda Gerry, recalls the then-old-fashioned approach to planting flowerbeds, often referred to as “bedding out”, whereby plants of one variety were massed together to produce single-color displays. In response to that outdated technique, Gerry notes, “there has come into existence a school of garden colorists that, consciously or otherwise, is adopting and adapting the idea of impressionistic painting to floral planting. They are demonstrating the garden flowers arranged in close juxtaposition of color will produce, not kaleidoscopic polychrome effects, but [an] amalgamation [of related, but not identical hues]”. [Photo: Example of bedding out courtesy Humphrey Bolton, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

One case in point was Marian Coffin’s white rose and perennial garden for Frederick Frelinghuysen’s Elberon, NJ estate (above). Here she used flowers that were predominantly white, but with little flourishes of red, yellow, or purple at the centers or on the tips of petals. She also used soft lilac asters, cream-colored gladioli, and blush pink anemones as they complemented the pure whites in the scheme and helped to create a luminous, dappled effect. Indeed, “by assembling in this garden flowers [that] give an effect of white rather than those that are absolutely without color…a radiance is obtained…quite different from the lusterless albino effect frequently observed in ‘white’ gardens”. In this way, Coffin and other like-minded designers were generating an atmosphere of color directly inspired, Gerry felt, by the sparkling color techniques of the Impressionist painters. [Photo: From Belinda Gerry, “The Garden Colorists” in The Architectural Record, Vol. LII, July-December 1922]

Marian Coffin was also deeply influenced by Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932), by Charles Platt (1861-1933), and by the fashionable Edith Wharton (1862-1937). Jekyll, the grand dame of English landscape design, was a strong proponent of the use of native plants, and was an early adopter of impressionistic color palettes. She was also very assured in her employment of garden ornament, taking cues from Italian gardens and paying special attention to the relationship between ornament and architecture. Platt, a successful American architect and designer whose Italian Gardens (1894) reinvigorated the study of Italian Renaissance gardens, loved using semi-circular features at the ends of rectangular gardens, and figural fountains in pools, two design elements that Coffin often borrowed. Wharton, known mainly for her literary achievements, was also a keen gardener and garden designer. Her book, Italian Villas and their Gardens (1904) was as influential as Platt’s in bringing the Italianate style-with its symmetrical and highly structured schemes-to the forefront of American garden design.

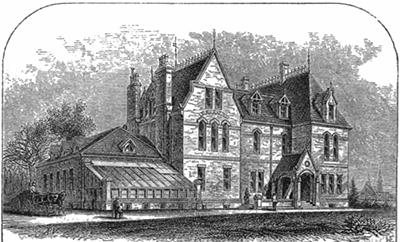

Coffin was particularly keen on promoting the importance of trees in gardening, since flowerbeds typically got most of the glory. She wrote dozens of articles for magazines, but published only one book: Trees and Shrubs for Landscape Effects (1940), in which she discusses the critical role of trees as design elements. In this volume, Coffin reminds the reader that trees “screen unsightly objects, they camouflage the service quarters and form the background to garden and lawn. They are planted to frame in far views, to give the effect of distance and to create vistas”. Her interest in trees was fueled by her studies in Cambridge, MA, not only at M.I.T., but also at the Arnold Arboretum and the Bussey Institution, Harvard University’s centers of horticultural research. Trained by the Arboretum’s master horticulturalists, Professor John George Jack (1861-1949) and Director Charles Sprague Sargent (1841-1927), Coffin had a very firm grasp on the nature of trees, how they would grow, and how they would affect the bones of her gardens over time. Paying close attention to trees also meant that she was not just designing formal flower gardens close to the house, but was instead laying out the whole property, from entry gate, to driveway, to more distant forested areas on site. Coffin shaped the entire landscape, and was brilliant in her ability to plan for the evolution of shrubs, beds, and tree lines through the years. [Photos: Top, The Bussey Institute, Century Illustrated Volume 12, 1876, public domain via Wikimedia Commons; bottom, Arnold Arboretum (Path up Bussey Hill) courtesy Bostonian13, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Marian Coffin’s devotion to trees led to the creation, under her direction, of a number of arboreta, both private and public. In 1922, Coffin was hired to design the gardens of Hillwood, the Brookville, Long Island estate of Marjorie Merriweather Post and E.F. Hutton. This property included formal gardens with topiaries and a substantial arboretum filled with magnificent specimens, including Japanese Pagoda Dogwood, Tulip Trees, American Elm, and Norway Spruce. Coffin typically planted mature trees of thirty to forty feet to give, as she noted in her May 1924 House and Garden article on the Post/Hutton project, an “impression of great age” to a landscape that had only just been constructed. Happily, Hillwood, a veritable Gold Coast masterpiece, was acquired by Long Island University in 1951 and has been largely preserved. As of 2002, the Community Arboretum, comprised of many of the trees planted by Marian Coffin, is open for public enjoyment.

Coffin also established arboreta at Clayton, the Childs Frick estate, in Roslyn, Long Island; Winterthur; and the University of Delaware, among other locations. Clayton, now occupied by the Nassau County Museum of Art, features an arboretum (pinetum) with more than 200 rare conifers in addition to forested ravines and a 450-foot formal flower garden. [Of special note: the Museum’s formal garden has been painstakingly restored in recent years, making it a prime spot to see Coffin’s work in person. Conservation efforts are ongoing, with special attention paid to the teak trellises installed at the south end of the formal parterre. This impressive structure, designed in 1931 by the architectural firm, Milliken-Bevin, in conjunction with Coffin’s plans, rates as one of our nation’s finest examples of classical-style treillage. [Photos: Archival photo of formal garden and photo of trellises courtesy Nassau County Museum of Art]

Some of the greatest projects of Marian Coffin’s career were the gardens at Winterthur. Her work there, completed 1929-31 and 1956-57, was fostered by the lifelong friendship she shared with Henry Francis du Pont and their mutual respect and passion for horticulture. They were childhood pals, but also studied at the same time with many of the same brilliant teachers at the Arnold Arboretum and the Bussey Institution. H.F. du Pont was obsessive about plants and about flowers in particular. For decades, he was deeply involved with the planning and planting of his own garden at Winterthur. Coffin and du Pont had a profound partnership, with Coffin giving shape and structure to du Pont’s expansive vision.

Coffin certainly left her mark on du Pont’s singular property. In 1929/30, Coffin oversaw the design and construction of the stone stairway that leads from the main house down to the pool. This steep allée, perpendicular to the axis of the main house, was an elegant solution to the estate’s hilly, wooded terrain.At the midway point of the stairway is a rounded terrace with figural sundial, providing a focal point viewed from both the house and the pool. The far end of the rectangular pool is finished with a formal semi-circular planted bed, one of Coffin’s signature geometric elements. In 1957, just prior to her death, Coffin planned and executed the Sundial Garden at Winterthur. Although completed at the end of her career, this garden is classic Coffin. A quintessential example of Coffin’s formal circular schemes, the garden also exhibits her penchant for billowy, not-too-clipped shrubs and luminous color. [Photos: Winterthur stairway and Sundial Garden aerial view courtesy The Winterthur Library, Winterthur Archives; recent image of Sundial Garden plantings courtesy W. Gary Smith Design]

Marian Cruger Coffin established herself early on as a long-term landscape architect, providing continuity and guidance as her gardens matured. Her instinctual, ongoing commitment to the landscape made her particularly successful as the University of Delaware’s lead landscape architect from 1918-1952. She first got the job through Hugh Rodney Sharp (1880-1968), a member of the University’s Board of Trustees. Coffin had created masterful gardens at Gibraltar, Sharp’s Wilmington estate, beginning in 1916 (completed 1923) and Sharp, along with cousins H.F. du Pont and Lammot du Pont Copeland, insisted that she be hired at the University. Coffin oversaw the transformation of the landscape there, making brilliant use of allées, oval lawns, and circular features to visually unify the men’s and women’s campuses (which was no small feat considering the misalignment of the axes). In addition to the formal gardens, Coffin planted a large number of specimen trees, including a circle of Magnolias and rows of majestic Elms, many of which survive. In her 1919 report, Coffin pledged that she would create “a unique example…of what a College can be when planned from the outset as a complete whole”. She felt strongly that “good planning…is bound to express in the most…beautiful manner…the life and aims of the institution”. Most importantly, Coffin was one of very few women who designed institutional gardens, and perhaps the only one who held such a high post for so many decades. [Photo: South Green with Memorial Hall in the foreground, University of Delaware, Newark, DE courtesy Cargoudel GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Marian Cruger Coffin established herself early on as a long-term landscape architect, providing continuity and guidance as her gardens matured. Her instinctual, ongoing commitment to the landscape made her particularly successful as the University of Delaware’s lead landscape architect from 1918-1952. She first got the job through Hugh Rodney Sharp (1880-1968), a member of the University’s Board of Trustees. Coffin had created masterful gardens at Gibraltar, Sharp’s Wilmington estate, beginning in 1916 (completed 1923) and Sharp, along with cousins H.F. du Pont and Lammot du Pont Copeland, insisted that she be hired at the University. Coffin oversaw the transformation of the landscape there, making brilliant use of allées, oval lawns, and circular features to visually unify the men’s and women’s campuses (which was no small feat considering the misalignment of the axes). In addition to the formal gardens, Coffin planted a large number of specimen trees, including a circle of Magnolias and rows of majestic Elms, many of which survive. In her 1919 report, Coffin pledged that she would create “a unique example…of what a College can be when planned from the outset as a complete whole”. She felt strongly that “good planning…is bound to express in the most…beautiful manner…the life and aims of the institution”. Most importantly, Coffin was one of very few women who designed institutional gardens, and perhaps the only one who held such a high post for so many decades. [Photo: South Green with Memorial Hall in the foreground, University of Delaware, Newark, DE courtesy Cargoudel GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

While the majority of Marian Coffin’s commissions were constructed between the late 1910s and the late 1920s, she worked steadily from the time she opened her office in 1905 until her death in 1957. She became a fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1918 (an honor more prestigious than standard membership bestowed upon only a couple of women at the time). Then, in 1930, the Architectural League of New York awarded Coffin the Gold Medal of Honor for projects completed in Connecticut and New York. She was one of the most sought-after landscape architects in the United States, easily holding her own against her male contemporaries. In a letter to H.F. du Pont in the first years of World War II, she remarked that she, “for one absolutely require[d] beauty to keep going at all”. Lucky for us, she created beauty just about everywhere she went.

[Photo: Reflecting pool in the Gibraltar garden, Wilmington, DE courtesy Mandy Jansen, Flicker,

20101016, Gibraltar Gardens 20, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

A selection of extant Marian Cruger Coffin gardens open to the public, and further reading:

- University of Delaware, Newark, DE

- Long Island University-Post Campus, Community Arboretum, the former Edward F. Hutton and Marjorie Merriweather Post estate, Brookville, NY

- Gibraltar, the former H. Rodney and Isabella du Pont Sharp estate, Wilmington, DE

- Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, the former Henry Francis du Pont estate, Wilmington, DE

- Mt. Cuba Center, the former Lammot and Pamela du Pont Copeland estate, Greenville, DE

- Nassau County Museum of Art, the former Childs Frick estate, Roslyn Harbor, NY

- Cynthia Zaitzevsky, Long Island Landscapes and the Women who Designed Them, 2009.

- Nancy Fleming, Money, Manure & Maintenance: Ingredients for Successful Gardens of Marian Coffin, Pioneer Landscape Architect 1876-1957, 1995.